Hyponatraemia Inquiry: 25 medics still employed

- Published

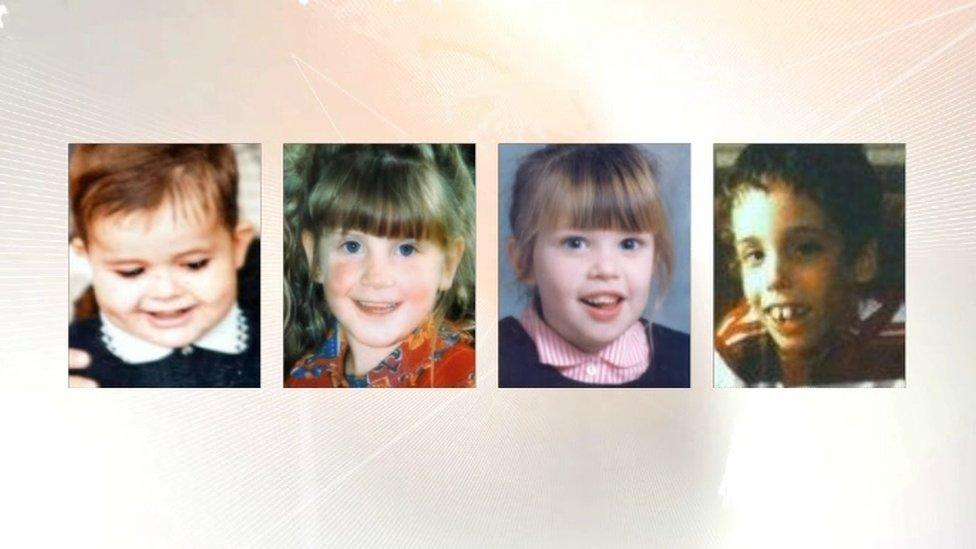

Adam Strain, Raychel Ferguson, Claire Roberts, Conor Mitchell and Lucy Crawford (not pictured) died after the level of sodium in their blood became abnormally low

Twenty five medical staff named in a highly critical report into the death of five children are still employed by Northern Ireland health trusts.

The Hyponatraemia Inquiry was set up to examine the deaths at the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children.

Hyponatraemia can occur when the level of sodium in the blood becomes abnormally low.

The child deaths took place between 1995 and 2003. The inquiry into the deaths found four were avoidable.

The BBC can reveal that sixteen doctors and nine nurses named in the inquiry report are still employed by a Northern Ireland health trust.

The information was obtained in response to a Freedom of Information request sent by the BBC to the Belfast, Western and Southern health trusts.

The latest developments comes as five medical royal colleges say they owe it to the Hyponatraemia Inquiry families to minimise the risk of such a tragedy recurring.

In a joint statement, five royal colleges - the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; Anaesthetists; Pathologists; Surgeons and Surgeons of Edinburgh - said transparency within the health system was vital.

They proposed the creation of a new board to hold health trusts and civil servants to account.

Their response supports the vast majority of the 96 recommendations made by Justice O'Hara in January after the 14-year inquiry,, external and stresses the importance of honesty, transparency and tightening reporting.

The Department of Health has said detailed work is continuing in response to the inquiry's recommendations, promising further details would soon be made public.

Analysis: Parents may never have closure

By Marie-Louise Connolly, BBC News NI Health Correspondent

It is the longest running public inquiry in British history and one of the longest running stories I have worked on.

The Hyponatraemia Inquiry examined matters of the utmost gravity - the deaths of five children in hospitals.

What impact has the report - and its 96 recommendations - had? Very little.

The report - not to mention the five deaths - has only been mentioned only once in Parliament, when the former MP who set up the inquiry grabbed a window during a Brexit debate in the Lords.

Where are Northern Ireland's local MPs? Who cares?

While the bereaved families are keen to speak, doctors, nurses and managers named in the report are keener to stay quiet. No one I asked agreed to be interviewed.

That is unfortunate, as without honesty and transparency, there will be little change.

And without a health minister, justice minister or an executive, the report does not have a local champion.

So the 14-year inquiry is far from over.

For the parents, there may never be closure, but a more open and public debate about what happened might just start the healing process.

Duty of candour

The royal colleges are professional bodies for doctors. They support members, work to improve standards of patient care and develop policy and guidance.

Such a collective response is unusual and reflects the seriousness of the issue.

It backs the establishment of a board which would hold managers and civil servants to account for systemic failures.

It says the development of a statutory duty of candour should be "a high priority item", but that "the issue of criminal liability and its potential impact on patient safety must be carefully assessed".

BBC News NI Health Correspondent Marie-Louise Connolly explains the background to the hyponatraemia inquiry

The royal colleges also recognised the important role of patients and their families and said that children and parents or carers should be asked to help design services and shape care.

They further outlined the need for sufficient time for training healthcare professionals.

'Admit mistakes'

Dr Ray Nethercott from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health said their greatest sympathy was with the bereaved families.

"I work with colleagues who wake up every morning wanting to do the very best for the children they treat," he told BBC News NI.

"Nobody wants these tragedies to happen. But when they do, it's only right that we admit to mistakes and look closely at what went wrong, why, and who is accountable.

"I recognise now more than ever that healthcare delivery is extremely complex, it is incumbent on us all to seek ways to make it easier to understand and to much more clearly describe who has accountability when mistakes are made."

Dr Nethercott said the group had made an open offer to the Department of Health to work with them to implement the recommendations of the inquiry report.

- Published18 May 2018

- Published31 January 2018

- Published31 January 2018