Can getting a summer job influence your career path?

- Published

The number of 16-17 year olds with summer jobs almost halved over the past two decades

After weeks of being stuck inside doing exams while everyone else soaked up the sun, the long summer holidays are stretching out before students and school pupils.

While some will spend July and August enjoying a well-deserved break from the alarm clock, others will try to secure a big break into their dream career.

For many young people, a summer job provides their first experience of the real world, giving them responsibility and a degree of financial independence.

But can it influence your career path?

'Sweeping up'

Stephen Martin spent his teenage summers working on building sites around Belfast. He went on to become the boss of a large construction firm employing more than 500 people.

A former chief executive of Clugston Construction, Mr Martin is now the director general of the Institute of Directors (IoD) in London.

Stephen Martin is the current boss of the IoD, one of the UK's leading business organisations

The 52-year-old business leader says that a summer job can be a useful step up the careers ladder.

But did he ever get his hands dirty on the building sites?

"I didn't really have a choice because I wasn't a skilled operative, I wasn't a carpenter or a plasterer or bricklayer," Mr Martin recalls.

"So I would do the tidying up, the sweeping up, the clearing out - all the jobs that the other tradesmen didn't particularly want to do."

His time as a labourer helped to prepare him for his career in quantity surveying and later, taking the top job at Clugston Construction.

"It was fantastic to see, first-hand, the practical side and get the experience of what it was like to work as part of a team on a building site, rather than just reading about the theory," Mr Martin recalls.

"Seeing how architects work with surveyors, how it ties in with foremen... you could see how teamwork made the difference in delivering a successful project."

'Getting a tan'

If a building site isn't your thing, how would you feel about getting paid to sit on a sunny beach all day while still learning on the job?

Is it possible to top-up your tan and get paid for it?

If that sounds like the perfect compromise, if not a stroke of total genius, it's exactly what 18-year-old Abigail McBroom is doing.

The A-Level student from Coleraine, County Londonderry, has just started a summer job as a lifeguard with the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI).

She has been keeping watch at Benone Strand, while Northern Ireland basks in a highly unusual heatwave.

So, is it like a scene from Baywatch or the world's riskiest babysitting job?

Abigail is quick to point out there is "a lot more to lifeguarding than sitting on a beach and getting a tan".

Abigail McBroom is being trained to save lives while she waits for her A-Level results

Having spent her last two summers washing dishes in a café, this year she was determined to do something to help her career prospects.

"I want to study physiotherapy at university, so the first aid side of this obviously helps," she says.

"Physiotherapy is also a job that requires communication, so this will help me to address the public."

'Stressful'

She is one of about 85 lifeguards recruited by the charity in Northern Ireland this summer, who are paid by local councils for the onerous task of protecting thousands of adults and children.

Benone is an award-winning beach with seven miles (11km) of sand

RNLI lifeguard supervisor Karl O'Neill says it is a "fantastic job" but carries "terrible responsibility".

"You may have 2,000-plus people on the beach, you and your team are responsible for their safety on the sand and in the water for the duration of your day," he says.

"When it's busy, and you have rip currents and you have multiple numbers of people, it can be quite stressful, but our training supports lifeguards in how to deal with those situations."

As well as sea rescues, they cope with first aid emergencies, missing children and dune fires, one of which engulfed Benone in smoke this week.

Seven fire engines were sent to a sand dune fire at Benone on Tuesday

However, not all summer jobs are just about getting some work experience.

For many, their first pay packet is the most important factor, especially if money is tight at home, which was the case for the future leader of the IoD.

Minimum wage

When Mr Martin was 10, his father was killed in a work-related accident and by the age of 13, the schoolboy was working part-time in a butcher's shop.

"I was in a situation where I needed to have money and I needed to bring money into the household," he says.

A young Stephen Martin at a birthday party with his sisters

He added that his series of part-time jobs taught him budgeting skills and the "value of money" from an early age.

The youngest age at which a child can work legally in the UK is 13, external, but only on a part-time basis.

For full-time jobs, young people must reach the minimum school-leaving age, external, which varies across the UK.

In Northern Ireland, the cut-off point is 30 June on the year after you reach your 16th birthday.

However, employers are not obliged to pay the National Minimum Wage, external to school-age children.

Recent UK-wide research suggests a falling trend in teenagers involved in part-time work outside class hours.

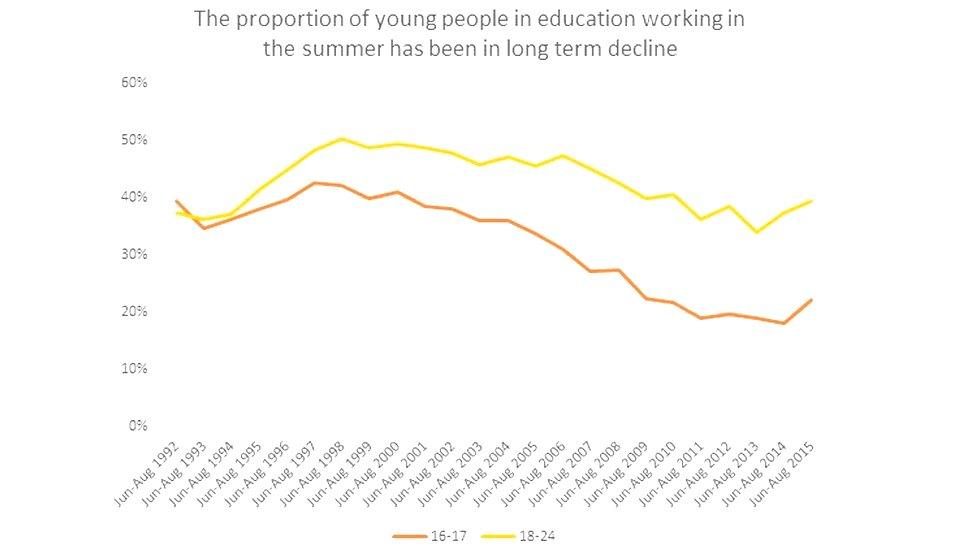

The number of 16-17 year olds who had summer jobs while still in full-time education almost halved in the UK between 1996 and 2016, according to the Progressive Policy Think Tank (IPPR), external.

For third-level students, the drop was less significant, but the number still fell by a fifth during the same period.

The IPPR recorded a declining trend since the 1990s using Office of National Statistics data

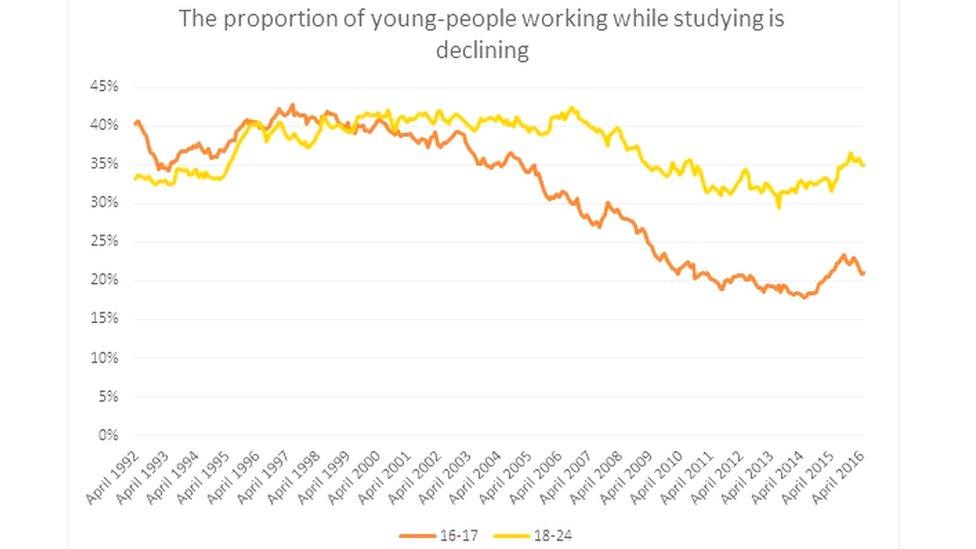

There was a similar picture when it came to part-time work during term time.

In the late 1990s, more than 40% of the UK's 16-17 year olds worked while studying, according to the IPPR, which cited "Saturday jobs" as an example.

'Exam pressure'

By 2016, the figure almost halved, falling to little more than 20%.

UK-wide figures show a smaller proportion of students are working during term time

But after months of exams, and a lifetime of work ahead of you, is spending your teenage summers behind a counter or a sweeping brush really the best use of your time?

"It's important that young people are still able to enjoy their summer holidays, because I appreciate the exam pressure that they're under," Mr Martin says.

"But I think that summer jobs can provide a fantastic opportunity to gain experience and that can really help when you get into the competitive jobs market."

- Published7 July 2018

- Published16 March 2016

- Published23 August 2016