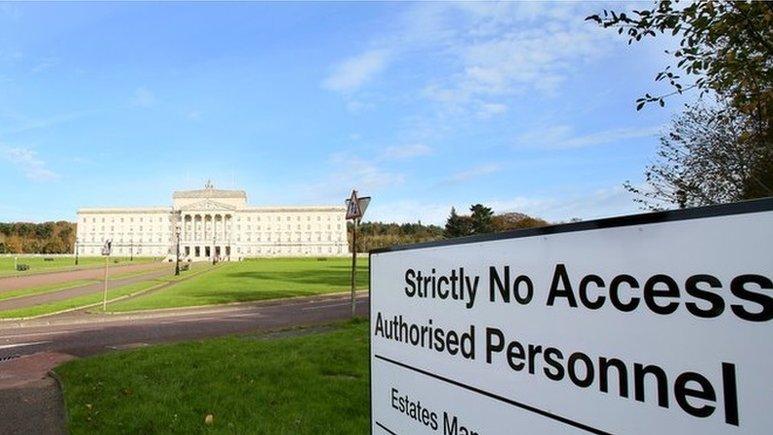

Stormont: No Guinness record for political ineptitude

- Published

We are well used to anti-climaxes in Northern Ireland - deals that turn out not to be deals, deadlines that are dead long before they become officially defunct.

So it was maybe predictable that we haven't even been able to claim a record for political ineptitude.

Guinness World Records decided Northern Ireland didn't qualify for the title of longest time without a peacetime government, currently held by Belgium, because it's a devolved administration rather than a sovereign state.

"I was a bit miffed on a personal basis," jokes elections expert Nicholas Whyte, "but I can see their logic. If you go beyond sovereign countries that meet the Montevideo criteria, external, that are in control of their own territory and can have diplomatic relations with other countries, if you move beyond that, then where would you stop?

"Would you stop with Northamptonshire County Council, for instance, which has just been suspended?"

Whyte has a unique perspective on the comparison between the stasis at Stormont and what happened in Brussels.

Elections expert Nicholas Whyte says he would be "astonished" if the Stormont stand off lasts 1000 days

When the visiting Professor at Ulster University isn't administering his website devoted to Northern Ireland elections, external, he's working in the Belgian capital as a political consultant , external.

Although the Brussels and Stormont standoffs bear similarities - both were fuelled by clashes between parties representing different language lobbies - in other ways, they are more notable for their contrasts.

In Belgium, Nicholas Whyte points out, everyday life was kept going by the continued functioning of five relatively powerful devolved administrations and the existence of a caretaker government in Brussels.

In Northern Ireland, it's been interventions by Westminster in passing Stormont's budgets which have staved off anarchy.

The statue of Sir Edward Carson at the Stormont estate

"The day to day impact [of the Belgian stand off] wasn't that awful," Mr Whyte recalls.

"In fact, economic growth was rather good, leading to one famous Belgian newspaper headline which read: 'Don't just do something, stand there'.

"It demonstrated the robustness of the Belgian system, perhaps, that once you have a properly devolved settlement that people actually believe in, they can manage for a while if one of those layers doesn't work, so long as it comes back in the end."

Protests

Guinness World Records' decision not to recognise the Stormont parties' achievement (if that's the right word) has robbed this month's milestone of much of its significance.

But official world record or not, there's no doubting the frustration that motivates those behind a series of "We Deserve Better" protests, external being planned to highlight the deadlock and the anger you often hear voiced on BBC Radio Ulster's phone-in shows, when topics like education or health funding are under discussion.

That frustration is mirrored by officials charged with keeping those public services going without any political masters.

"Things are difficult and they aren't getting any easier," one senior source lamented.

"I don't see an early resolution. There seems no prospect of the power-sharing executive returning anytime soon."

Arlene Foster and Martin McGuinness, before the executive collapsed

Last month, the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, expressed his hope that a new round of inter party talks could be launched, perhaps after the EU summit in October. But he indicated that would depend on the summit producing greater certainty when it comes to Brexit.

That proviso is quite a qualification. The arguments over Brexit could still be raging on unresolved by the end of this year.

Moreover, the exchanges between the Stormont parties sparked by Mr Varadkar's statement didn't inspire much confidence in their ability to resolve their differences over matters such as Irish language legislation.

Far from time proving a healer, the autumn will see more Brexit negotiations, more fractious hearings in the Renewable Heat Incentive inquiry, and a possible by-election in North Antrim.

Last month, the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, expressed his hope that a new round of inter party talks could be launched

The prospect of a difficult autumn leaves local officials wondering how long the current interregnum will last. Ever since a judge stepped in and overturned a senior civil servant's decision to approve a major waste incinerator in County Antrim, known as Arc 21, the Stormont departments have been caught between a political rock and a legal hard place.

There's a long list of major capital projects which cannot be advanced. Besides the Arc 21 incinerator, these include a proposed new Cruiser Quay and Power Plant at Belfast Harbour, the redevelopment of the GAA stadium at Casement Park in west Belfast and a planned new Transport Hub for Belfast City Centre.

In the wake of the incinerator judgement, Stormont officials aren't hopeful about two forthcoming legal challenges.

One involves the major road project upgrading the A5 which links Aughnacloy and Londonderry.

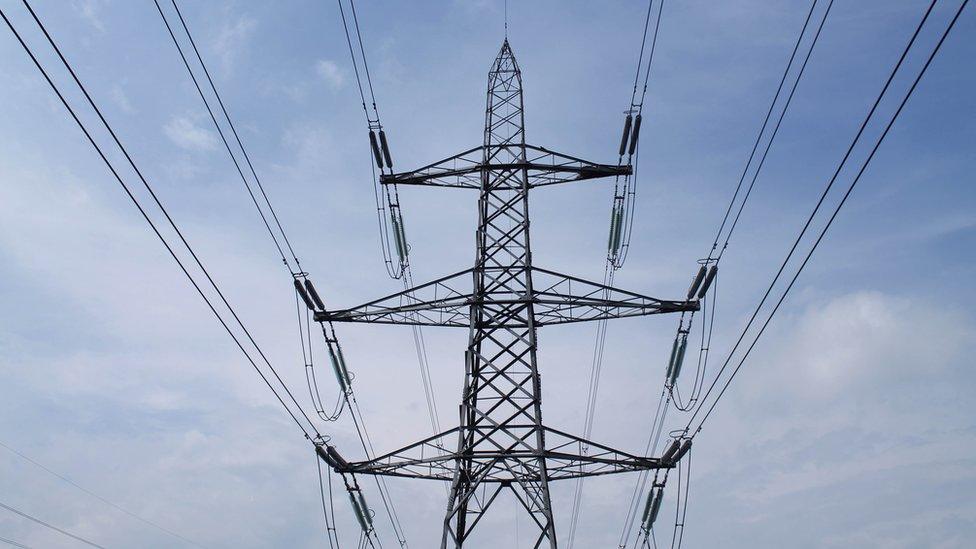

The other concerns a planned new North South Electricity Interconnector.

The interconnector is considered vital for the operation of the Single Electricity Market across Ireland and it's claimed that without it, consumers would lose out on a projected £20 million annual saving.

There is concern that energy infrastructure planning could be delayed by a lack of official strategy

However, both projects have their critics and both look vulnerable to the "silver bullet" argument that elected ministers, not unelected bureaucrats, are required to approve such significant planning developments.

If all these projects had been given the go ahead, their total worth is estimated at something between £1bn and £2bn. For now, however, the local construction industry has to make do without that investment.

The recurrent financial problems experienced by Northern Ireland's schools and hospitals can't be attributed directly to the Stormont stand off.

However, officials point out that the absence of ministers to approve school closures and mergers or the re-organisation of health facilities makes it impossible for the devolved administration to begin to tackle endemic problems.

Despite the growing sense of drift at Stormont, the Northern Ireland Secretary Karen Bradley has proved reluctant to intervene beyond setting a budget.

Northern Ireland Secretary of State Karen Bradley has been reluctant to call a fresh assembly election

Ministers remain convinced that getting into a period of direct rule from London would be much easier than getting out of it. Previously, when power sharing broke down, Tony Blair suspended the assembly and executive. But that power was removed from the statute books after the St Andrews Agreement of 2006, so it would require emergency legislation to restore it to the current government's armoury.

Westminster politicians often feel they are walking on eggshells when it comes to Northern Ireland. But this government's reliance on the DUP at Westminster, coupled with the fragility of the Brexit process, seems to have reduced the Northern Ireland Office to a state of near inertia.

When Leo Varadkar made his comment about a fresh round of talks, for example, the NIO appeared completely blindsided by the intervention.

'Slow decay'

Despite some positive recent employment figures, senior officials note that local economic growth is not keeping pace with either the Irish Republic or other UK regions.

"There is no obvious cliff edge moment," says one source gloomily. "Instead, we are seeing a slow decay across our public services and economy."

In September, a judicial review being brought on behalf of victims of historical institutional abuse will be heard. The victims had been promised financial compensation by a judicial inquiry. However, that has been delayed indefinitely as a result of the political stalemate.

One argument the victims' lawyers are expected to deploy will be that the Mrs Bradley's reluctance to call a fresh assembly election has been unreasonable. But even if a judge orders a fresh poll, few commentators believe it would radically change the balance of power between the Stormont parties.

The "We Deserve Better" argument may gain traction, but it would come up against the electoral might of the traditional green/orange divide.

Nicholas Whyte thinks it's "very strange that we haven't had a move either towards formal direct rule or towards calling new elections".

He says he would be "astonished if the Stormont stand off lasts 1000 days....it seems to me that the Brexit deadline (next March) will be a very tight moment which will concentrate minds. I'd be really surprised if we are still having this same conversation next summer, but we might still be having it at Christmas".

For now, the final duration of this period of deadlock remains anyone's guess. Whether it's 600 days or 1000 days, one thing is clear - you might be able to look the figure up in Northern Ireland's history books in the future, but you won't be able to find an entry for it in the Guinness Book of Records.

- Published9 August 2018