New NI parliamentary constituency plans redraw the map

- Published

It's the biggest shake-up of Northern Ireland's parliamentary constituencies since the 1990s.

The Boundary Commission for Northern Ireland's new proposals were published last Monday.

The shake-up is not entirely the commission's fault.

The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition (remember them?) legislated back in 2011 for the House of Commons to be reduced from 650 MPs to 600.

Northern Ireland's share of the pain? We had to lose one of the current 18 seats, taking us to 17 MPs.

The Boundary Commission, an independent body, had a difficult task.

The new boundaries had to respect local ties, not deviate too much from the old seats but also produce constituencies using electoral wards as building blocks, whose votes numbered within 5% of the national average (with a little extra wiggle room for Northern Ireland if necessary).

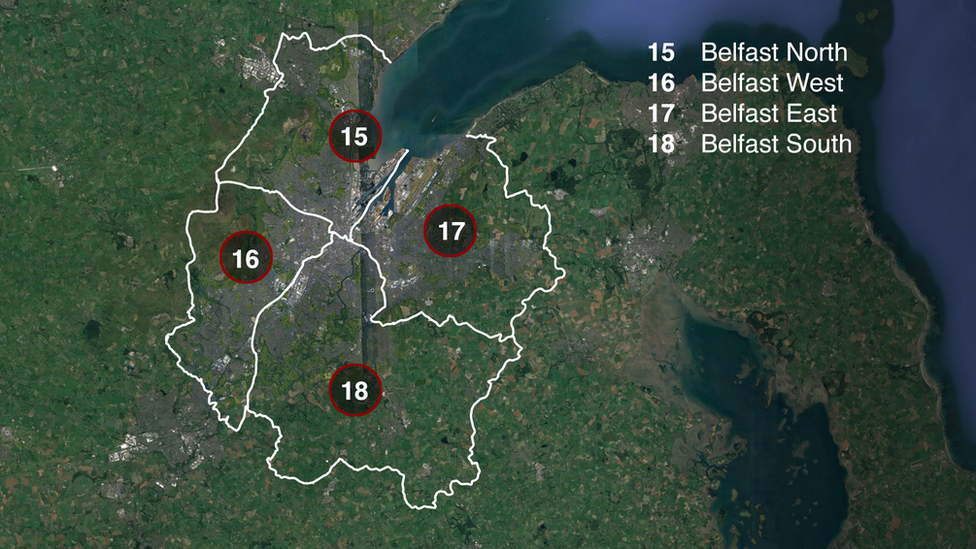

Their first draft, published in September 2016, reduced Belfast to three seats from four, but also shifted boundaries all over Northern Ireland.

Only Foyle, Newry and Armagh and South Down escaped major surgery.

Final recommendations

There was little public support for this plan - in particular, people in greater Belfast argued that the city should return four seats and many in the west of Northern Ireland argued for less drastic changes.

The commissioners' second draft, leaked and then published in January, took these issues into account, and actually moved far fewer voters into new seats than their previous plan had done.

It created problems of its own - some political parties felt it was less good for them, and better for others, than the first draft had been.

Several towns were treated badly by the brutal mathematics of geography, notably Dungiven and Glengormley.

The third and final set of recommendations, produced this week, has two further minor changes: Dungiven is now included in the new constituency of Sperrin (which is the old West Tyrone, extended northwards) and Mallusk stays in South Antrim rather than moving to North Belfast.

The four Belfast constituencies, the border seats, East Antrim, South Down, Mid Ulster and Upper Bann are not changed very much.

Grim logic for DUP

That accounts for all seven of Sinn Féin's current seats, and four of the DUP's 10.

The big changes are along a belt stretching from the north coast, down the east of Lough Neagh and then ending at the Ards peninsula - six seats, which are effectively squashed into five.

East Londonderry is replaced by the new seat of Causeway. Most of North Antrim becomes Mid Antrim. South Antrim is split several ways, and the new seat with that name actually has more of the old Lagan Valley in it.

The old Strangford largely becomes Mid Down. North Down loses Holywood to East Belfast but takes in the Ards Peninsula.

Independent MP Lady Sylvia Hermon could be the one to lose out under the new proposals

Five of those six seats are currently held by the DUP at Westminster, so the grim logic of arithmetic suggests that one of Gregory Campbell, Ian Paisley, Paul Girvan, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson and Jim Shannon may end up being the loser in the political version of musical chairs.

At the same time, the addition of the Ards Peninsula to North Down may not be very helpful for Independent MP Lady Sylvia Hermon, who has only a small majority over the DUP - though it should be noted that she argued for that change herself.

At assembly level, two of the SDLP's narrowest gains in last year's poll seem likely to be victims of the changes, in Lagan Valley (now South Antrim) and East Londonderry (now Causeway).

Rough guide

The UUP and Alliance will also lose seats in the Antrim shake-up.

The DUP however will be able to set off losses there against gains from Sinn Féin in the expanded West Belfast, and probably from the SDLP in East Londonderry.

So the projected result of last year's vote on the new boundaries would give the DUP 28 seats out of 85, Sinn Féin 26, the SDLP 10, the UUP would have nine, Alliance seven and the Greens would have two seats, with the TUV, People Before Profit and independent MLA Claire Sugden holding their single seats.

That, of course, is assuming the voters vote the same way in future Westminster or assembly elections as they did last year.

But that never actually happens, so these must be considered as only a rough guide to the new political landscape.

- Published10 September 2018