Reality Check: A plan to unlock the Irish border problem

- Published

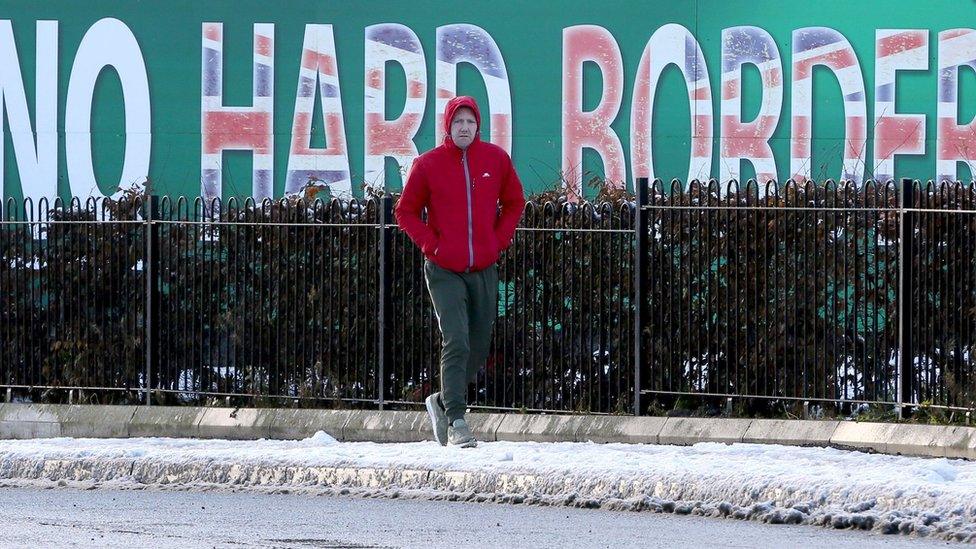

The Irish border is the single biggest sticking point at this stage of the Brexit negotiations.

The Prime Minister Theresa May has pledged to leave the EU's customs union and single market but at the same time has promised no hardening of the border.

That means no new physical infrastructure and no new checks or controls for customs or product standards

Her solution is the Chequers plan, with its "combined customs territory" and "continued harmonisation" with EU rules on goods and agriculture.

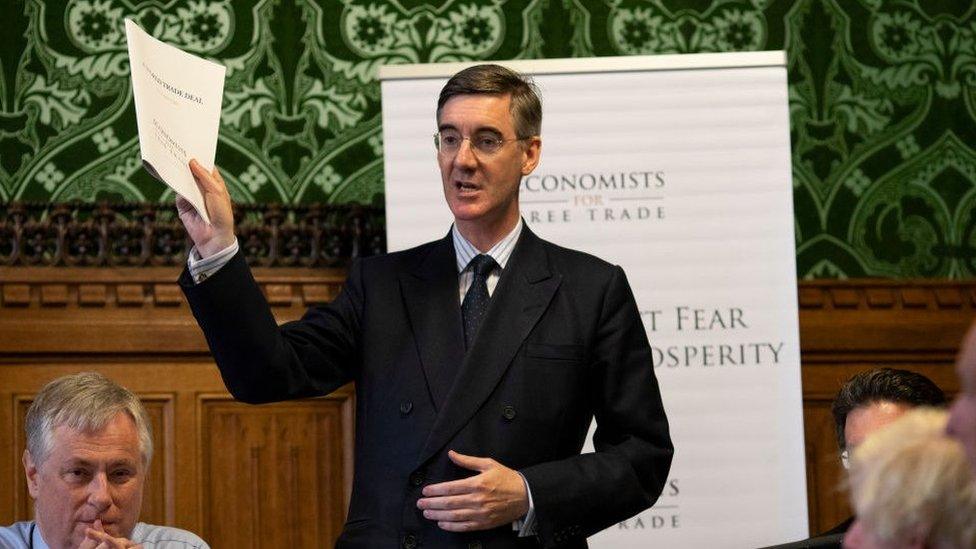

Now, the European Research Group (ERG), which backs a "clean-break Brexit", has suggested another way, which avoids the need to follow all those EU rules.

Jacob Rees-Mogg, who chairs the ERG, said it provided a solution for the Irish border "in a way that any reasonable person would think meets the requirements of the European Union's concerns over the single market".

It has similarities to an earlier government plan, which proposed the continuation of some existing UK-EU arrangements and the use of technology to make it easier to comply with customs procedures.

The Irish border: Brexit's 310-mile problem

Reality Check: The Brexit challenge for Irish trade

Reality Check: How much trade is there between UK and Ireland?

Perhaps the most difficult issue for the Irish border is the movement of food and agriculture products.

Those products are the major component of cross-border trade but they also face some of the strictest EU rules.

The rules mean consignments of food or animals can enter the EU only through specified border inspection posts.

Those involve mandatory document checks and a significant proportion of consignments must also be physically checked.

It is likely the challenge posed by those rules nudged the prime minister towards the "common rule book", which would involve signing a treaty committing the UK to continued harmonisation with EU rules.

The ERG approach is for an "equivalence" arrangement, where the EU would accept that, while UK food and agriculture rules would be different, they would still be as good as EU rules and would not put consumers at risk.

It backs this up with reference to a World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement on food and plant safety, suggesting this would require the EU to offer equivalence

However, many trade experts believe this overstates the particular strength of that agreement.

The ERG document also mentions the equivalence provision in the EU-Canada trade deal - but it doesn't add that under that deal there are still documentary checks on all meat and dairy imports, with 10% subject to physical checks.

The EU has been prepared to remove requirements for border inspection but only with countries that have adopted its rules.

Switzerland is an example - it modifies its laws in response to changes in EU legislation and must monitor third-country exports at EU-approved border inspection posts.

So, the sort of equivalence the ERG is hoping for would mean a unique approach by the EU.

One intriguing aspect of the ERG report is that, when it comes to agricultural products, it approves of the existing arrangements that mean the whole island of Ireland is a "common biosecurity zone".

This means that animals being moved from Great Britain into Northern Ireland are subject to checks and controls, even though this is an internal UK movement.

Those animals need an import licence and the exporter needs to arrange for an approved vet to examine the animals before they leave for Northern Ireland.

The vet will then apply for an export health certificate. An animal transport certificate is also required.

The animals and all the paperwork are checked on arrival at Larne Harbour, County Antrim.

The report says: "It has been recognised by all communities on the island of Ireland that it is sensible to capitalise on the protection afforded by the sea."

Does that leave the door open to additional checks, for example, of food products, that are being imported from Great Britain into Northern Ireland?

That would eliminate the need for border inspection posts but is unlikely to be approved of by the Democratic Unionist Party, whose support in Parliament the government needs.

And again, this is an area where a flexible approach would be required by the EU as there is no other example of a common biosecurity zone between the EU and a region of a non-EU country.

Another area where the ERG is hoping for an accommodating approach from the EU is on VAT.

The report proposes that the UK would have continued access to the EU's VAT Information Exchange System (VIES).

That would help avoid the need for VAT liabilities to be assessed by customs officials as products arrived at the Irish border.

The ERG also describes the VAT system as providing a framework for streamlining customs controls.

That streamlining involves:

filing documents electronically

the use of licensed customs brokers

having any inspections at the factory rather than the border

Familiar plans for "trusted trader" schemes are also laid out.

The concern for small businesses in particular is that this is not frictionless trade - it means more red tape and the use of customs brokers, for example, would mean additional costs.

More fundamentally, it is not at all clear on what terms the EU would allow continued access to the VIES and if those terms would be acceptable to the ERG.

Would the UK agree to continued adherence to the EU VAT Directive and oversight from the European Court of Justice?

Would the UK seek an even deeper VAT agreement than the one Norway was - an arrangement that took four years to negotiate?

- Published12 September 2018

- Published11 September 2018

- Published29 June 2018

- Published19 January 2018

- Published4 December 2017