Energy regulator asked about green scheme failings - RHI inquiry

- Published

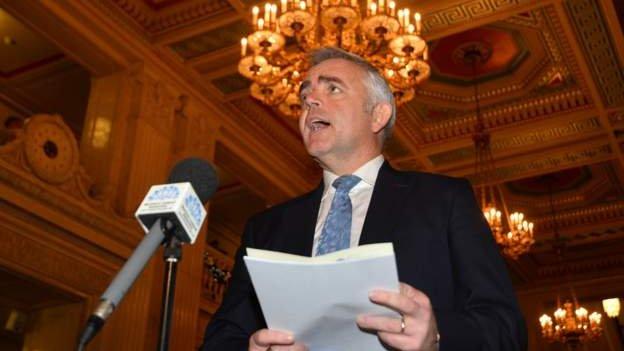

Dermot Nolan has been the chief executive of Ofgem since 2014, the government body that has oversight for energy schemes

The body that regulated Northern Ireland's flawed green energy scheme has been asked about its apparent failings at a public inquiry.

The role was being undertaken by a division of the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem).

Its chief executive is appearing at the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) inquiry.

The scheme was set up in 2012 to encourage uptake of eco-friendly heat systems, but overgenerous subsidies left NI taxpayers with a £490m bill.

The scheme's failings led to the establishment of a public inquiry in January 2017.

Ofgem's main function is as a regulator, but a subdivision administers energy initiatives, as it did with the Northern Ireland RHI scheme.

But it did not consider it part of its job to alert Stormont's enterprise department - which had created the RHI scheme - about the potential for abuse to occur.

Dermot Nolan, who has been chief executive of Ofgem since 2014, said the organisation believed its role was to check that applicants were complying with the letter of the regulations, not the spirit.

'Odour of gaming'

The inquiry has already heard evidence about so-called "gaming" of the scheme, where claimants could exploit RHI by putting in multiple boilers to maximise their subsidy payments.

It was one of the biggest reasons for the scheme's disastrous overspend.

The rules were so vague that multiple boilers were allowed on a single site, as long as they were on separate heating systems.

The inquiry heard that Ofgem did not tell the enterprise department that multiple boilers were a feature of the Northern Ireland scheme until late 2014 or early 2015.

By that stage, the budget was already under huge pressure.

RHI claimants could effectively earn a profit by burning wood pellets in their boilers, and some installed multiple smaller boilers to be eligible for the most lucrative subsidy

Inquiry chairman Sir Patrick Coghlin said it seemed Ofgem was much better placed to consider the issue of gaming than the department.

Ofgem had the ability to smell the "odour of gaming" in the RHI scheme, but did not pass it on, he added.

Mr Nolan said he accepted the department could not have spotted gaming without Ofgem's help, but that both agencies did not think about gaming, adding: "I regret that."

"Both organisations are culpable there, I certainly put Ofgem in that."

Ofgem's contractors were going out to farms and factories to check that boiler installations were compliant.

'Problem'

The inquiry has already heard that there was some difficulty about the sharing of data between Ofgem and the department.

The department did not get installation audits from Ofgem.

Sir Patrick said: "When you step back and see that the audits weren't even sent...then you really have a problem."

Mr Nolan said the audit reports had not been shared with the equivalent department in Great Britain either, which was running the RHI scheme there.

Sir Patrick said that did not make the situation any better.

Mr Nolan said Ofgem had a much more proactive relationship with the department running the RHI scheme in Great Britain, than the enterprise department in Northern Ireland.

He said the energy department had done much more work to identify flaws in its scheme and had even set up a "gaming" register.

Sir Patrick asked why that learning had not been shared in Northern Ireland, given that both Ofgem and the enterprise department were government bodies.

He suggested some straightforward co-operation could have avoided many of the problems in the scheme.

Mr Nolan said he now accepted that Ofgem should have been talking to the enterprise department about gaming.

'Up in smoke'

Later, the inquiry was told of fresh details of a letter sent by a company involved in selling renewable fuel to Ofgem that exposed serious flaws in the RHI scheme.

It sent the letter to the then head of Ofgem - Andrew Wright - in December 2013, drawing the body's attention to allegations of gaming in the Great Britain scheme.

It said it was aware of a "growing number of sites" where RHI was being used to heat chicken sheds with multiple small boilers to get the bigger subsidy, as opposed to one larger boiler - which would have been more energy efficient but not as financially attractive.

It claimed it knew of one farmer ordering 33 boilers to "game" the scheme.

At that point, only 59 installations had been accredited on the NI scheme, but inquiry counsel Joseph Aiken suggested that was exactly the type of information Ofgem should have been passing onto the enterprise department.

He gave details of an email from a trade body to Ofgem, which also suggested some claimants were running their boilers to heat empty sheds - the inquiry has heard evidence that some claimants on the NI scheme also did this.

None of the concerns about the RHI scheme flagged with Ofgem were passed on to civil servants running a similar initiative in Belfast

The inquiry also heard about an article in a magazine, Farmers Weekly, in May 2013, in which a poultry farmer who was a claimant on the Great Britain RHI scheme, explained why he had 11 smaller boilers.

He knew he could install more boilers to maximise his profits.

The article was flagged up in Ofgem's risk log, but it did not pass on any of the information to civil servants in Belfast.

Sir Patrick Coghlin said it was "one of the clearest cases" he had seen of the scheme being manipulated.

'Major systems failure'

Mr Nolan said he could only offer his explanation that Ofgem did not see monitoring gaming as its function, and therefore did not communicate any of those claims to the enterprise department.

Mr Aiken put it to Mr Nolan that this was "literally public money going up in smoke" and that Ofgem did not "need to put a gaming badge on it".

He suggested the cumulative effect of Ofgem's lack of communication could point to a "major systems failure".

Mr Nolan said he would have to reflect on the evidence he had been presented with, and come back with a more detailed written response.

As part of its work in administrating the RHI scheme, Ofgem contracted inspectors to carry out audits of biomass boilers to ensure they were being used in compliance with the regulations.

But the number of audits carried out was far fewer than should have been the case - the inquiry has already heard there were just 31 audits across the first three years of the scheme's operation.

In that time, there had been more than 2,000 applications: the 31 audits amounted to 1.46% of those applications, well below the intended level of at least 7.5%.

Mr Nolan was also asked why the audit reports that were done were not forwarded on to the enterprise department.

He said they were considered part of routine administration, not something that needed to be shared with officials - and had they been asked for, they would have been provided.

'Sobering'

Inquiry panellist Dame Una O'Brien asked whether Ofgem could have been more proactive, instead of adopting a stance of: "If they don't ask, they don't get."

Mr Nolan said the information the inquiry had provided to him was "sobering", and he admitted Ofgem was "far from perfect" in its work.

He was also asked why applicants due for inspection got a three-week warning.

He said Ofgem did not believe if applicants were abusing the scheme that they could cover it up in three weeks.

He said he hoped that answer did not sound "too glib".

Mr Nolan gave evidence to the RHI inquiry throughout Friday, which marked the 100th day of hearings.

The oral sessions are expected to finish at the end of October.

- Published25 September 2018

- Published21 September 2018

- Published20 September 2018

- Published14 September 2018

- Published13 September 2018

- Published12 September 2018

- Published11 April 2018

- Published11 September 2018

- Published11 September 2018

- Published7 September 2018

- Published7 September 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published13 March 2020

- Published4 September 2018

- Published17 April 2018