How an old kitchen stove ended up as museum exhibit

- Published

It took weeks for this Victorian cast iron range to find its perfect home

It was black, shiny and imposing. Our Victorian cast-iron range had stood, pride of place, in our kitchen for more than 100 years.

Although, for the 14 years that we have lived there, it has never emitted a scintilla of heat into our freezing cold kitchen.

Six months ago, we decided we had to modernise and planned to introduce a modern substance called "insulation".

We dreamed of a future in which our kitchen would resemble other people's kitchens - one that didn't require you to wear a hat in the winter. One that was warm.

We debated, talked about it and finally agreed - the large, old dear that had caught everyone's eye when they walked into our kitchen, would have to go.

'Huge hunk of metal'

Although we never put fuel inside, it had its purpose. It had been home to our bread-bin, empty vases awaiting flowers and piles of bills, school calendars and children's pictures.

So what do you do with a huge hunk of metal? Well, I phoned salvage yards on both sides of the border. Somebody must want it, I thought to myself.

The range became a storage cupboard for a bread-bin, empty vases, bills, school calendars and pictures

But no - "too big", "no market", "not functioning".

The builders' arrival was now imminent and we tried to sell it online.

No luck.

The builders were now going to be on site within a few days, but there was no way I could reconcile the idea of putting it in a skip.

Strange as it may sound, we knew far too much about its earlier life to let it end up in a dump.

As the kitchen was demolished, the urgency to find an owner for the stove grew

We had discovered that the man who bought our range and had it installed back in the early 1900s was a Mr Robert Smith.

Mr Smith was the first owner of our house and he had lived here with his wife, Jane, their four children and a maid.

But we knew a lot more about him than what we had gleaned from the censuses and the Belfast Street Index.

Shortly after we moved in, we discovered two long, metal receipt spikes in our attic. They belonged to Mr Smith and held a record of every penny he had spent over a quarter of a century.

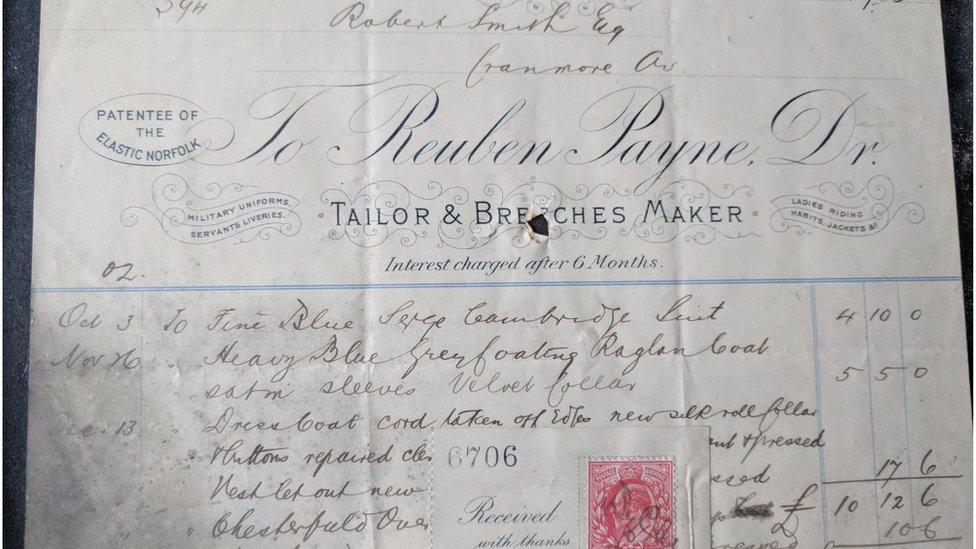

A copy of a tailor's receipt found in the attic

A clerk at E&W Pim Ltd, as well as a landlord, he was a man of money. A well-dressed man who had bought a coat at the Ulster Cloth Hall in Belfast's Chichester Street in 1903.

This was no ordinary coat, this was a "navy blue, grey floating raglan coat" with satin sleeves and a velvet collar.

Mr and Mrs Smith had beautiful furniture. They owned a Japanese embroidered fire screen and mahogany and velvet chairs.

They spent time on holiday in the Royal Hibernian Hotel in Dublin.

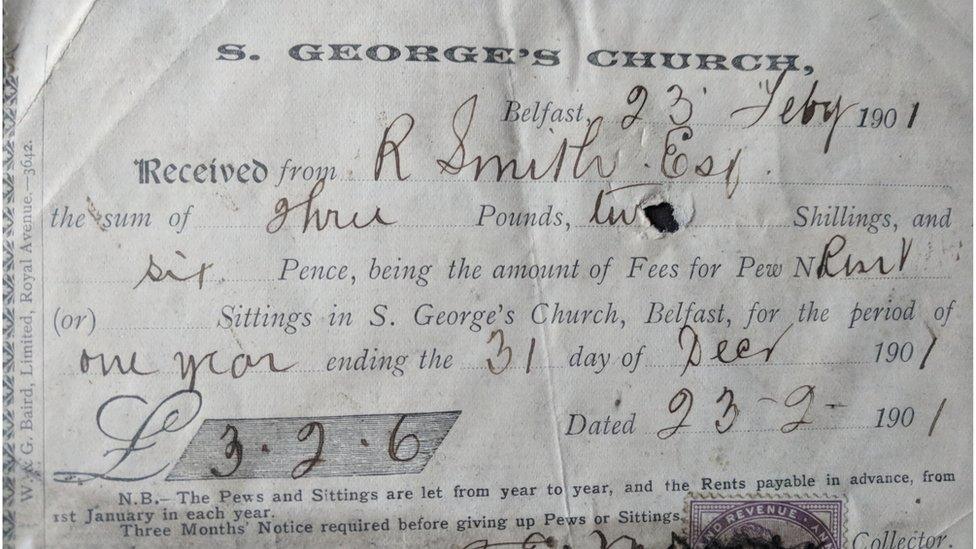

He bought a pew at St George's Church and was an avid reader of the Belfast News Letter.

Mr Smith bought a pew at St George's Church in Belfast

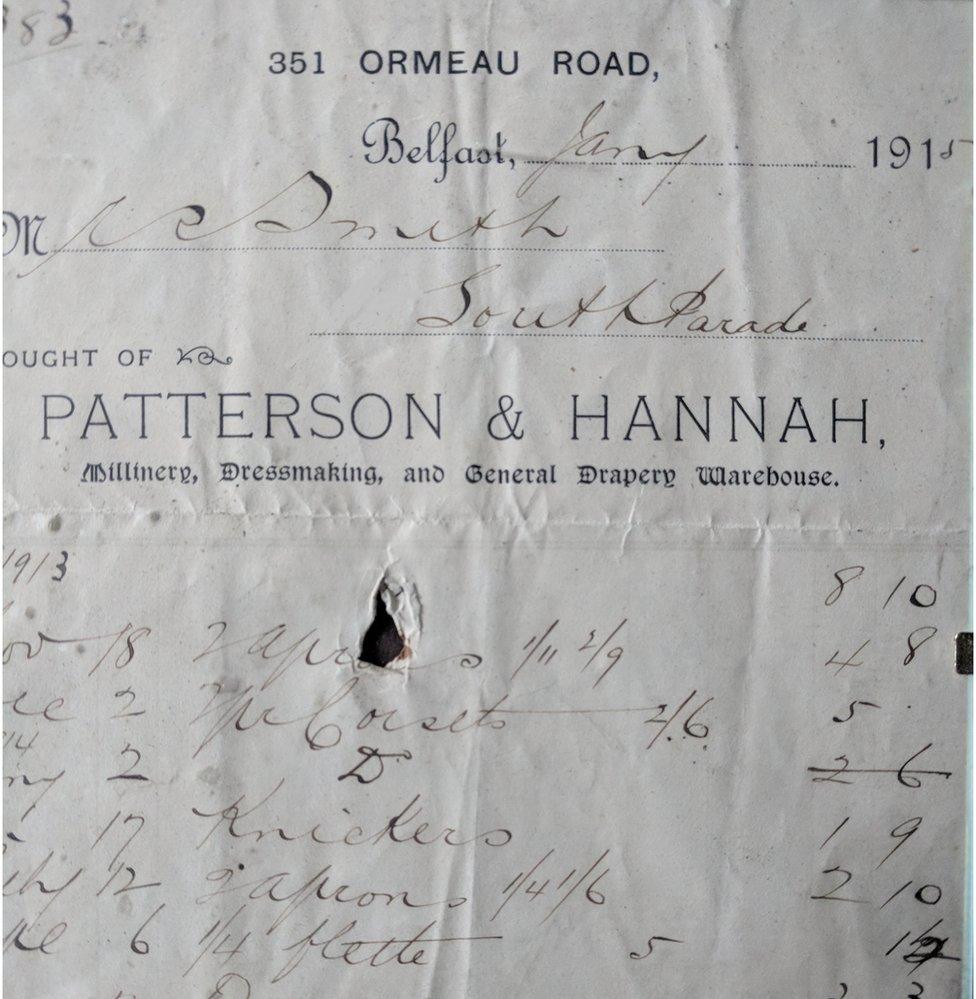

Jane, his wife, bought meat, milk, stout and bread on the Ormeau Road - things she, or her maid, would have cooked on our range.

I couldn't let it go.

In a last ditch effort to find it a good home, I phone the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum in Cultra.

They appeared interested, but not enthusiastic. They asked for photos. I sent them.

Time was running out.

A receipt from a draper dating back to the early 1900s

The following day, I received an early-morning call from Fiona Byrne, the Curator of History at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum.

She was enthusiastic. The museum loved our range. They wanted our range. It had provenance!

Fiona told me that the range's most significant feature was its Riddell brand.

'Significant family'

"Riddell was a well-known iron monger company, in fact at one time it was the largest in Ireland. John Riddell, who established it, became a significant man in Belfast, as did his family.

"His daughters Eliza and Isabella pioneered female education and established Riddell Hall at Queen's University, which is now a major conference centre. They also provided sponsorships to help female students get third-level education.

"John Riddell's sister Mary married into the Musgrave family - another significant Belfast family. Henry Musgrave, a nephew of John Riddell, went on to inherit a company which was a sister firm to Riddell, which also dealt with ironmongery and Musgrave stoves were exported throughout Europe."

So, working at speed because our builders were demolishing our kitchen around it, the museum organised a team to come and view it.

Our wonderful builders painstakingly removed the surround, tile by tile. Even the tiles were special - 5cm fire tiles imported from Kilmarnock. Expensive.

Several hours later, they rolled our range out through our hall and loaded it onto a lorry.

The tiles around the stove were imported from Kilmarnock

The best bit about this story is the fact that our range - Mr and Mrs Smith's range - will be preserved, lovingly restored and will go on display at the Cultra museum.

Not only that, we were told that it may eventually end up adorning either the parochial house or the bank manager's home on the site.

This fact made our children beam with both joy and pride.

Our range had found a new home living in the past and we could one day go and visit it.