American troops, murders and a race riot during World War Two

- Published

What's the connection between a racial clash in Antrim and the murder of a Belfast pimp?

Both incidents happened during World War Two and both involved American soldiers based in Northern Ireland.

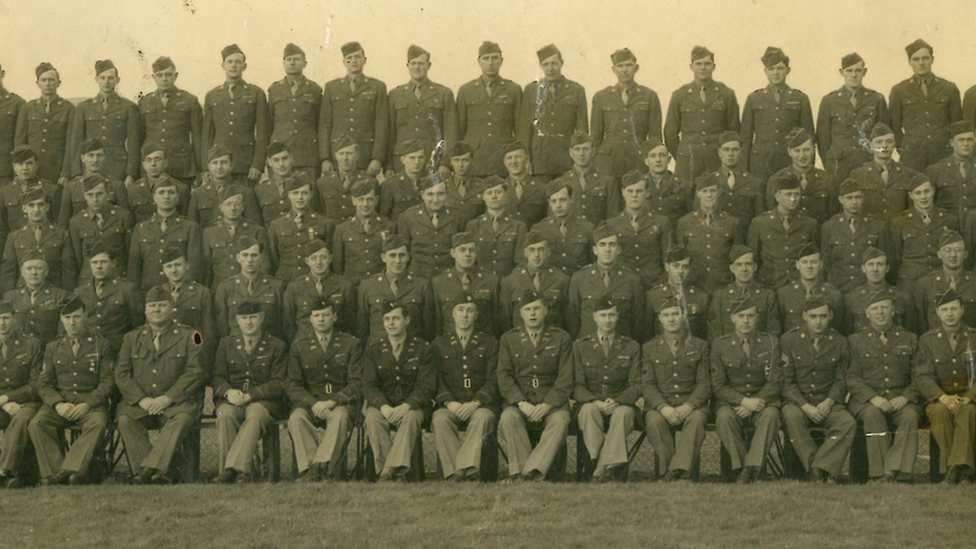

At one stage during the war, US military personnel made up about one tenth of Northern Ireland's population.

An estimated 300,000 Americans were based in Northern Ireland or passed through between the beginning of 1942 and the end of the war.

Nearly 2,000 Northern Ireland women became GI brides, starting a new life in the United States after the war.

US personnel were based all over the country as they prepared to fight in North Africa and later the invasion of Normandy on D-Day.

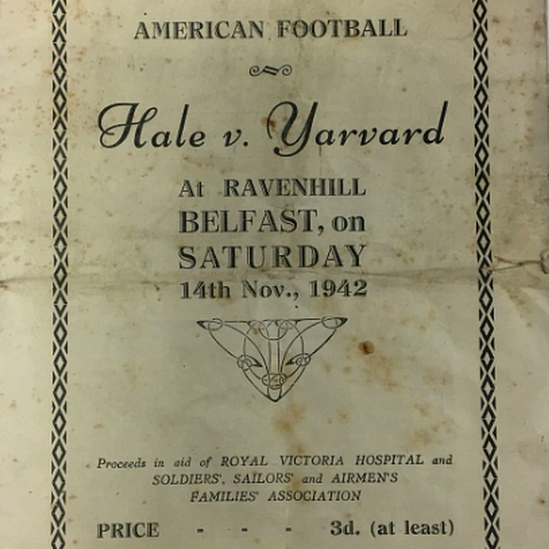

American football matches at east Belfast's Ravenhill stadium were among the events staged during World War Two

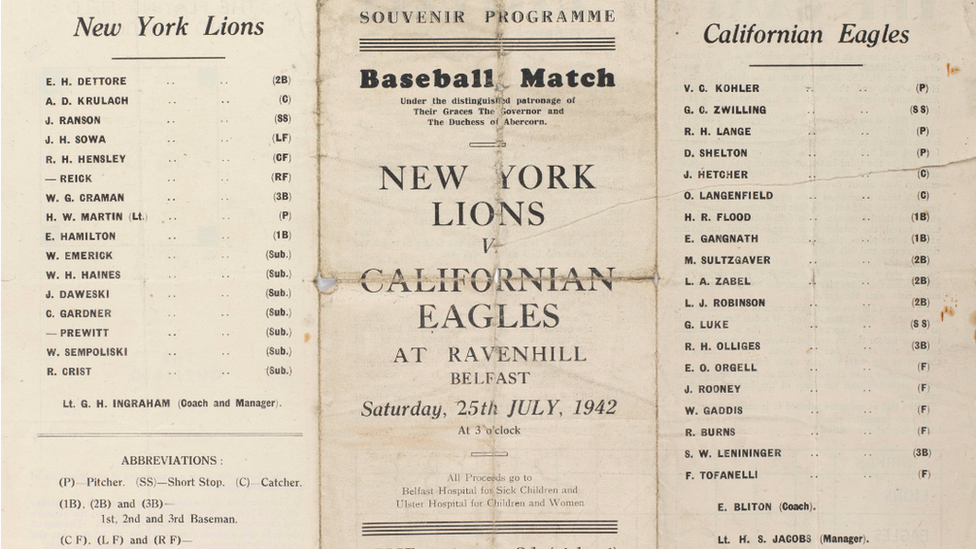

As well as training for upcoming military campaigns that would help the Allies win the war, they staged American football and baseball games in Belfast.

The proceeds went towards local hospitals, set up a fund for orphans of the Belfast Blitz and made toys for kids in the children's ward of the Royal Victoria Hospital at Christmas 1942 and 1943.

While their interactions with the population were overwhelmingly positive, there was a darker side to their presence.

It's a story that's been researched by Alan Freeburn, learning and collections officer of the Northern Ireland War Memorial.

He says the boredom facing some of the troops led to many cases of drunk and disorderly behaviour, striking officers, soldiers going AWOL and theft.

However, there were also a small number of much more serious cases, two of which resulted in American soldiers being executed for murders carried out in Northern Ireland.

Race riot

Antrim was the scene of a confrontation between white and black troops in September 1942.

It's fair to say details of the incident are rather sketchy.

A New York Times report from the time states that a black US soldier was fatally stabbed in a brawl with white US soldiers outside a pub in Antrim. A white soldier also suffered serious gunshot injuries, but survived.

The report quotes a statement from the Headquarters of the United States Army in Northern Ireland.

"Several shots were fired before the disorder was ended," it said.

"One soldier was killed, the victim of knife wounds. Another soldier was seriously wounded. No civilians were wounded."

Thousands of US soldiers passed through Northern Ireland during World War Two

Alan Freeburn has read US Army files that discuss the incident.

He says African-American soldiers from the 28th Quartermaster Truck Regiment, based at Lough Road Camp, were in their mess hall to watch a film on the night of 30 September 1942.

That night reports came through that a fellow soldier from the camp had been attacked and three others, including their staff sergeant, had been detained.

In response, Pte George McDaniels and other men of G Company stormed an ammunition room in a nearby Nissen Hut and set off for Antrim to "get the MPs [military police]" and to release their sergeant.

Mr Freeburn says they clashed with white soldiers returning from a dance with local women.

Pte McDaniels was later court martialled for "an assault upon Corporal Theodore B Janusz by shooting him in the side of the body with a dangerous weapon".

The soldiers passsed on their love of American sports

Corporal Janusz survived and testified during the court martial that he was returning to his camp "after he had taken his girl home" when 20 black soldiers called him over as he neared a bridge.

He said he was knocked to the ground with a rifle butt and, fearing for his life, got up and ran.

Pte McDaniels fired two shots at the fleeing corporal, hitting him once.

McDaniels was found guilty and sentenced to dishonourable discharge, forfeiture of all pay and confinement for five years.

The other most serious cases were:

Killing of Edward Clenaghan, County Down

Forty-seven-year-old Edward Clenaghan's mother ran Clenaghan's bar on the Soldierstown Road between Moira and Aghalee.

In September 1942, Pte Herbert G Jacobs, 23 from Kentucky, and Pte Embra H Farley, 27, from of Arkansas, both soldiers of H Company 13th Armored Regiment, were inside the bar and were described as "having consumed a considerable amount of intoxicating liquor".

Ravenhill also hosted a baseball match between teams from New York and California

They refused to leave and stole bottles of beer until finally persuaded to vacate the premises. Fifteen minutes later the window of the pub was smashed.

The publican's eldest son James Joseph Clenaghan left to remonstrate with Jacobs and Farley, while his brother cycled to report to the commanding officer of the nearby American camp.

"Later that night a Mr Samuel Hendron, who was cycling home from Moira train station, found Edward unconscious at the side of the road. He was brought to Lurgan hospital but he died that morning due to a fracture of the skull," Alan Freeburn says.

A Northern Ireland boy gets to check out a US Army jeep

Farley and Jacobs had been due to be on guard duty that night but didn't turn up. They were arrested the next day.

A court martial was held in October in Castlewellan. They were found guilty of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years hard labour in Ohio.

"The evidence was pretty much stacked against them. The jurors decided that without doubt they were the ones responsible for it, but they couldn't determine who had struck the fatal blow," Mr Freeburn says.

"But they were found with Edward's bike, there was blood on their overcoats. They couldn't decide who did it, so they charged the two of them together."

Murder of Henry Coogan, Belfast

Wiley Harris Jr was the first US soldier to be sentenced to death for a murder carried out in Northern Ireland during World War Two - a sentence that provoked protests and pleas for a stay of execution.

Harris was in a Belfast city centre pub, before relocating to an air raid shelter with a local prostitute.

Henry Coogan, described in newspaper reports of the time as a dockworker, but in reality believed to have been a pimp, said he would keep watch during the tryst.

However, after a short time he interrupted Harris and the woman, falsely claiming police had arrived.

An American military band performs in NI

A fight ensued, before Harris stabbed the Belfast man 17 times with a switchblade.

Harris was court martialled and sentenced to be hanged.

"There were protests," Mr Freeburn says.

"The Marquess of Salisbury, leader of the House of Lords at the time, telegrammed President Roosevelt saying that 99% of the population were indignant at the verdict and asked that the sentence be postponed to cement the Anglo-American friendship.

"The leaders of the local Catholic, Presbyterian and Methodist churches made a joint appeal the night before the execution to stay the execution."

However, the protests were to no avail - Pte Harris was executed on 26 May 1944 in Shepton Mallet Prison, Somerset.

Patricia Wylie, Killycolpy, County Tyrone

Pte William Harrison was the only American who was convicted of child murder in the UK during the Second World War.

"He clearly had mental health issues," Mr Freeburn says.

"He was diagnosed in April of 1943 with constitutional psychopathic state and inadequate personality along with hysteria and amnesia.

"However, a board found - even though at this point he had resorted to alcohol to cope - he had no definite mental illness and it was recommended that he be returned to duty."

Pte William Harrison was the only American who was convicted of child murder in the UK during the Second World War

In June of 1944 Harrison was subject to court martial for going AWOL and inflicting injuries on himself. He was sentenced to six months hard labour which was due to end on Boxing Day 1944, but his station commander remitted it on 23 September.

Two days later, Harrison persuaded a reluctant member of the Wylie family to let seven-year-old Patricia accompany him to a shop to buy minerals and sweets.

But he later attacked and killed Patricia, whose body was found behind a haystack half a mile from their home in Killycolpy.

"You almost get the sense it could have been very easily avoided [if Harrison had not been released]. It was incredibly tragic," says Mr Freeburn.

While the Harrison case in particular is horrific, it should again be stressed that considering the sheer number of US military personnel who served in Northern Ireland during World War Two the number of serious criminal cases involving them is tiny.

Almost 2,000 women from Northern Ireland became GI brides

Generally, the US servicemen and women - including African American soldiers - got on very well with the population of Northern Ireland.

However, for a small number of NI people their interaction with the liberators of Europe was a violent and in some cases fatal, and their stories should not be forgotten.

- Published19 May 2014