The sculptor who mended Great War soldiers' shattered bones

- Published

Anne Acheson: The artist who changed medical history

An artist from Northern Ireland made the breakthrough in resolving one of the biggest medical dilemmas facing soldiers injured in World War One.

Anne Acheson's achievement is all the more remarkable because it was made when women did not even have the vote.

As a sculptor, she went on to develop plaster of Paris for use in treating limb injuries.

She pushed it on to widespread acceptance, despite resistance by the medical establishment.

Lifelong disability

Before her pioneering work many of the wounded faced lifelong disability, or even amputation of broken limbs.

It was her detailed understanding of human anatomy, learned while studying at art college, combined with her experience as a volunteer helping injured soldiers, that led to the breakthrough.

Her pioneering work has been retold in a new BBC Two Northern Ireland documentary.

Wounded soldiers flooded into London from the battlefields of Belgium and France

Anne was born in Portadown, County Armagh, and benefited from an education that was progressive for the time.

Her work is hard to find now but, between the wars, it was popular and as well as sculptures, she made mascots for racing cars.

Anne was a student at the Belfast School of Art, and moved to the Royal College of Art in London after winning a scholarship in 1906.

In 1914, she was confronted with the consequences of the war, as injured men were flooding back from the front for treatment.

Dr Emily Mayhew says Anne would have seen wounded soldiers every day in London

According to historian Dr Emily Mayhew: "If you lived in central London at that time, you were engaging in that end of the war.

"She would have seen nurses, doctors and, most importantly, wounded men, every day of the week.

"She would have seen a lot of patients on crutches, because they were amputees, or because they had these limb problems."

Many of Anne's neighbours were going out after work, volunteering at the hospital.

Bandages

"Quite often they were doing quite basic things, like putting together kits and rolling bandages. So she would have been in an environment in which pretty much everyone she knew, and everyone she saw had engaged with the war," says Dr Mayhew.

Anne joined a women's voluntary group called the Surgical Requisites Association (SRA) and worked with injured troops for the rest of the war.

As Anne's biographer David Llewellyn explains, the treatment of broken bones was a particular problem: "The Tommies were being shelled and the shells were exploding over their heads.

"So they would put their arms over their heads to protect their faces and the shrapnel would break a bone - the humerus, radius or ulna.

"They would then be crudely splinted. That meant the fracture would often have been reduced, but by the time they got back to Britain 10 days later, the bones were back to where they were - they were broken or not aligned."

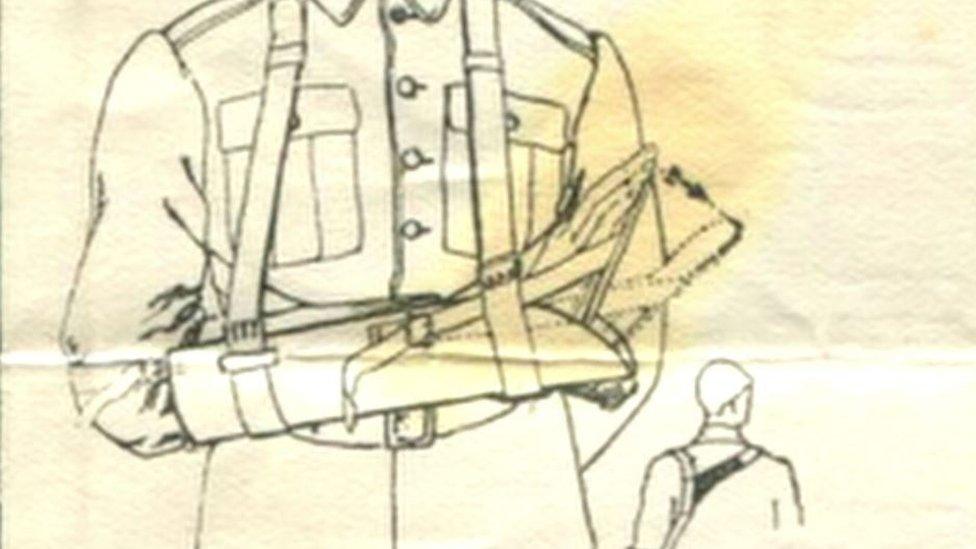

Anne's initial splint designs were effective but time consuming to make

The SRA was asked to come up with a cradle to help with the recovery of soldiers with broken arms.

Anne and a colleague came up with one that was a great success, but they were time consuming to make and she wanted to take things a step further with a customised treatment.

So, using her artistic background, Anne turned to plaster of Paris as an alternative - thereby changing medical history.

Dr Mayhew says finding a way to treat fractures was the single, greatest medical need of World War One, as more injured soldiers were being kept alive than ever before and the vast majority had orthopaedic injuries.

Anne's use of plaster of Paris was inspired by her artistic practice

The medical profession was slow to adopt her technique, even though the bones could still be x-rayed when a patient was wearing a cast.

Anne's technique was eventually adopted, and she was made a CBE in 1919.

In 1938 she became the first woman elected as a fellow of the Royal British Society of Sculptors.

Anne volunteered again during World War Two, working in London for the Red Cross during the Blitz.

In later years, Anne moved back to Northern Ireland and continued her artistic career

She eventually moved back to Northern Ireland to continue working as an artist.

You can see Anne Acheson: The Art of Medicine on BBC Two NI at 22:00 on 4 November.

- Published23 August 2018