Calls for memorial to Dungannon workhouse dead

- Published

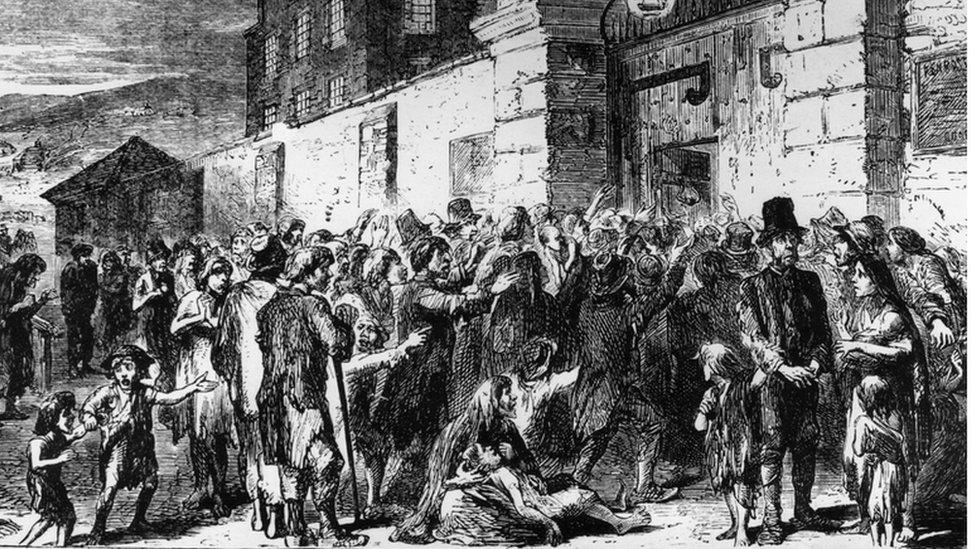

At times during the Irish famine of the 1840s the hungry clamoured to enter the workhouses

Mid-19th century Ireland was a bleak place.

"A lot of people only had a holding of half an acre," said Bertie Foley of Donaghmore Historical Society.

"Out of that, they had to feed their family, and they had to make enough money to pay the rent. And they couldn't do it."

As poverty and starvation increased, workhouses began to open - ostensibly to offer succour and survival.

But there was a saying that the road to the workhouse was the road to death, and for thousands it was.

The mass grave at Dungannon overlooks an estate of newly-built houses

Dungannon was no different. The workhouse there was built in 1840, on the grounds of what is now the South Tyrone Hospital.

Opened in 1842, it was designed to accommodate 800 people, but up to 1,200 at a time ended up calling it home.

"When they went in, that was it for the family," said Bertie.

"The women went to one side, the men to the other, the children to yet another part of the building. And they almost never saw each other or spent time together again."

About 2,000 people died in the workhouse and its adjacent fever hospital in the century the site was in operation - 700 of them in the early years.

Bertie Foley would like to see a permanent memorial to the many workhouse inmates buried in the unmarked grave

They were buried in a large-scale paupers' grave, beneath quicklime in a bid to limit the spread of disease.

But there was nothing to record who they were, or even to say for certain how many were interred there.

Now there are houses being built on the ground below where the graveyard was.

The developers, Radius Housing, commissioned a small-scale dig to try to ascertain the boundaries of the graveyard.

The findings of the archaeologists will be presented in a report.

The developers commissioned a small-scale archaeological dig at the site

There is nothing left of the workhouse now, although a plaque on Quarry Lane, some distance from the site, does say the workhouse existed.

But as development continues close to the site, Bertie and the society believe what remains of the bodies of those buried here without ceremony or marker should be commemorated.

"The bell of the old workhouse is still in the hospital - it controlled the lives of everyone here, you only moved or did anything on the ringing of the bell," said Bertie.

"There should be something here at the back of the hospital, above where these houses are being built, to say they lived and died here - a stone plinth, in a flower bed maybe.

"They had a silent death, completely unremarked upon.

"If we don't remember the past, in my opinion, I don't believe we have a future."

- Published20 November 2018