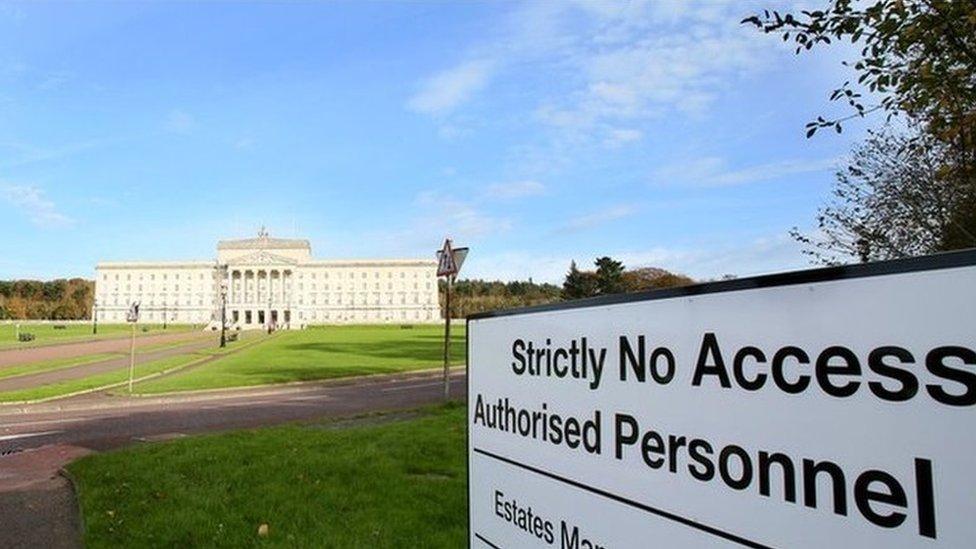

Stormont stalemate 'putting children's health at risk'

- Published

- comments

The research came from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Ireland

The political stalemate in Northern Ireland is putting children's health at risk, according to a new report.

The research came from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Ireland.

It found that the two years without an executive has led to "no real progress" in child health policy.

It showed that the mental health of children is getting worse and that a quarter of children are obese or overweight.

The report calls for an end to the political deadlock and for leadership that puts "children's health before politics".

In 2017, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) delivered a major report that made a series of recommendations for improving the health and wellbeing of children across the UK.

Now it has produced a "scorecard" for each of the four UK nations and the situation in Northern Ireland is described as not as encouraging as in the other devolved nations.

It found that a child death overview panel has yet to be implemented - despite legislation being introduced to establish it.

Northern Ireland has had no government since January 2017, when a power-sharing deal collapsed

According to the report, this makes it harder to learn from child deaths in Northern Ireland and prevent cases reoccurring.

It found that the Protect Life 2 strategy on suicide prevention remains in draft form and without a focus on children.

The scorecard revealed no progress in preventing child obesity - it said there are no plans to extend the measurement of children so data is captured after birth, before school and in adolescence.

There are also no plans to reduce the proximity of fast food outlets to schools, colleges, leisure centres and other places where children gather.

Breastfeeding

The report found no progress had been made in other areas including delivering high-quality health education to children and developing research to drive improvements in children's health.

This, it said, was "even more concerning" in light of Brexit.

Dr Ray Nethercott says optimism that the situation would be resolved has turned to dismay

However, the report said that despite the absence of a functioning assembly and executive, progress has been made in several specific areas.

These include road safety, with a new graduated driver licensing system due to be introduced in Northern Ireland in 2019/20, and home safety - health-visiting services and home-safety equipment schemes are being delivered.

On breastfeeding, the Department of Health has continued to monitor progress against the current strategy and have published a mid-term review on its implementation.

'Most alarming'

Dr Ray Nethercott, from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, said that in the two years since the Northern Ireland Executive collapsed, optimism that the situation would be resolved has turned to dismay.

"This scorecard reveals child health policy has stalled and where progress had been made before dissolution - a draft Children and Young People's Strategy and a draft Suicide Prevention Strategy - the absence of ministers and MLAs has meant that very little policy development or implementation have been achieved since.

"What I find most alarming, especially in light of the recent hyponatraemia related-deaths inquiry, is that Northern Ireland remains without a child death overview panel.

"Without it, we cannot fully learn why children die and prevent future deaths.

"Our political system lacks leadership and as a result, is in a chaotic state.

"I urge politicians from all political parties to put an end to this damaging deadlock, put children's health before politics and put child health at the top of the agenda before it is too late."

The RCPCH found that the Scottish Government has published "bold plans" aimed at tackling child poverty, obesity and mental health and, in Wales, a series of measures have been outlined to reduce childhood obesity rates and to protect children from alcohol exposure.

In England, it praised the government on its commitment to child health, commending them on pledges in areas such as mental health and the integration of children's health services.

- Published24 September 2018

- Published30 November 2018

- Published7 August 2019