Age limit at children's hospital emergency unit 'should rise'

- Published

Patients aged 14 and over cannot use the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children's ED

The mother of a severely disabled boy has criticised the age limit imposed by Northern Ireland's only dedicated hospital emergency unit for children.

The Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children's emergency department accepts patients up to the age of 13, but those older than 14 must go to adult A&E.

Monica McCann's autistic son is 15 and so is too old for the children's ED.

She said exceptions should be made for teenagers with learning disabilities who struggle to cope in adult settings.

The Belfast Health Trust apologised for any distress caused to Ms McCann's son.

The Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children is currently being rebuilt and the trust plans to raise the patient age limit to 16 and "up to 18 years for some specialist services".

Belfast is the only part of Northern Ireland which has a separate hospital for children, so in other towns and cities people of all ages use the same EDs.

'Daunting place'

However, the treatment of young teenagers in adult wards is "becoming an increasingly big issue" in the health service, according to the president of Ulster Paediatric Society, Prof Mike Shields.

He told BBC News NI the current system should be "flexible" - especially when dealing with severely disabled teenagers.

Ms McCann spoke out after spending several hours with her son, James, in Northern Ireland's busiest ED - Belfast's Royal Victoria Hospital (RVH).

James and his mother Monica spent hours waiting to be seen in the adult ED

"James has a severe learning disability, autism, and ADHD [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder]," she explained.

"He is 15, but he behaves like a three or four-year-old."

She added: "Adult A&E for any child is a very daunting place, but for a child with learning difficulties it's more daunting."

James had been ill over a 10-day period earlier this month and last Sunday, after a number of visits to the family doctor, his mother brought him to the RVH ED for tests.

"With autism, if you think of all their sensory needs - the bright lights, the noise - all that stuff in a busy A&E," she said.

'14-year-old adults?'

They were in the waiting room for almost four hours, and Ms McCann said: "There were no toys and nothing to stimulate him."

She described how she tried to distract James by singing and reciting nursery rhymes, but she was conscious that they were in a room full of sick patients.

"It was particularly busy. I'm sure there were 100 people and you can imagine the range of their needs and behaviours and issues that they're all dealing with," she recalled.

The RVH is home to Northern Ireland's busiest ED with more than 98,000 attendances in 2017/18

Ms McCann said James received "excellent service" when he eventually saw a doctor, but she contrasted the adult waiting room with previous visits to the children's ED, which incorporates toys and play into the patient experience.

The mother of three teenage boys also said that, "irrespective of his learning disability", James was too young to be treated alongside adults and she called for the upper age limit to be raised for all young teenagers.

She asked: "Are we deeming that 14-year-olds should be treated as adults?

"Because in any other circumstance they're not treated as adults, they can't vote until they're 18."

Apology

A spokesman for the Belfast Health Trust said: "Staff at the RVH Emergency Department will endeavour to do all they can to assist those with special requirements, however in exceptionally busy periods, unfortunately this is not always possible.

"Belfast Trust is disappointed to learn that the mother of this young patient felt that there was no support for her while she waited and we would take this opportunity to apologise for any distress this may have caused."

Could there be a simple solution?

On the outskirts of Belfast, one health care professional has already taken matters into her own hands in order to make the hectic ED environment more welcoming for autistic patients.

Joanne McConnell, a nurse at the Ulster Hospital in Dundonald, was inspired to set up a dedicated "quiet space" for patients after witnessing an autistic teenage boy struggling with a "sensory overload" in the crowded ED.

Ulster Hospital nurse Joanne McConnell set up dedicated room for autistic patients last year

The nurse, who has two autistic sons at home, recognised the teenager's distress from her own family experience.

"The only place we had free in that area was a small room, that I was able to convert into a quiet space, I wouldn't call it a sensory room", she said.

"With no funding within the NHS, we were able to put together some jigsaw mats, some beanbags and we were able to decorate the room to make it look less clinical and just give them a quiet place to go."

The room was set up about a year ago and is now frequently used by autistic patients and others with learning disabilities or mental health issues.

"I would say that we're probably averaging two or three patients a day but there was one Saturday recently where we had five different patients through it, of varying ages," the nurse said.

Her team also introduced an "ED passport" which is a document given to autistic spectrum disorder patients when they arrive at reception.

It allows patients to list examples of things which might trigger distress and helps to improves communication between staff, carers and patients.

The initiatives earned Ms McConnell an award in the learning disability category at the 2018 Royal College of Nursing's Nurse of the Year prize-giving ceremony.

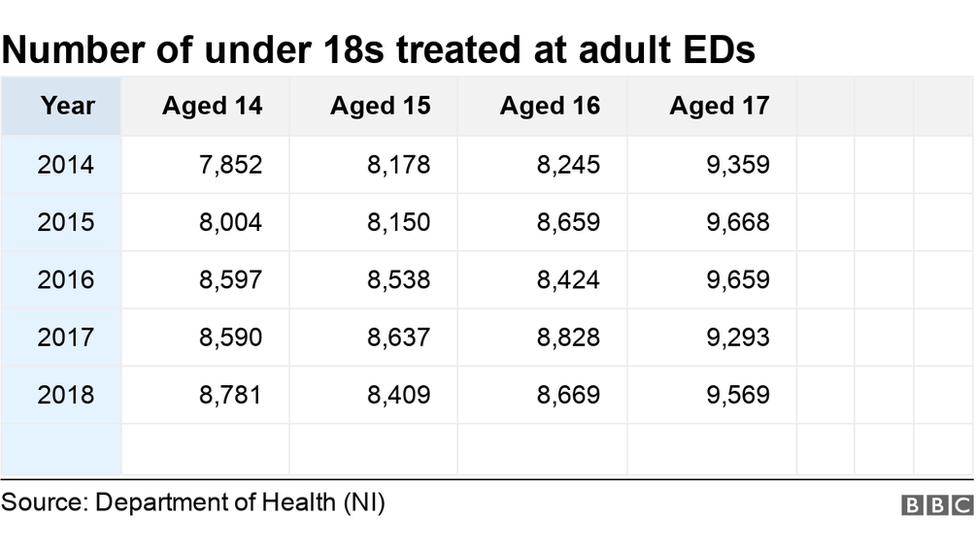

In the last five years, almost 175,000 teenagers aged from 14 to 17 have been treated at adult EDs across Northern Ireland.

The president of Ulster Paediatric Society, Prof Mike Shields, said there was a "grey area between 14 and 18" which can complicate matters for staff and patients.

"More and more children with very complex conditions, particularly with learning difficulties and complex neurological issues, are surviving longer and there is no real way of transitioning them [to adult services] at the moment," he said.

Belfast is the only part of Northern Ireland which has a separate hospital for children

Prof Shields added that the Department of Health has suggested that all paediatric services in Northern Ireland move to "a target transition stage of 16".

But he said the change would take time because he did not believe the children's hospital currently had the capacity to deal with complex adolescent health issues.

'No national standard'

He explained that paediatric surgeons were very experienced at diagnosing a range of abdominal conditions, such as appendicitis, but argued that if the age was raised to 16 or 18, then they would have to deal with teenage pregnancy and ectopic emergencies.

"That skill set isn't there at the moment and there would have to be a lot of training."

Prof Shields argued that the current system should be "flexible" when dealing with severely disabled teenagers and called for a "more organised transition" between child and adult health services.

The situation is not clear cut in Great Britain either, according to the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) which told BBC News NI there was "no national standard" on ED age limits.

"It is a local issue so it can vary according to commissioners (i.e. age 14/16/18)," its spokeswoman said.

- Published20 December 2017

- Published17 November 2015