Brexit: Irish border backstop still centre of debate

- Published

In a matter of days, MPs in Westminster will have their say on the prime minister's Brexit deal (again).

Will they or won't they?

With fewer than three weeks to go until Brexit day, the political drama enters its final act.

At the core of opposition to it: the Irish border backstop.

Since the PM's deal was first voted down in January, there's been all sorts of talk about how she might get changes to it, in order to win-over Brexiteers in her own party and enough in Labour's ranks too.

The key to much of that also involves securing the support of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), whose 10 MPs prop up the government in a confidence-and-supply pact.

Why is the backstop the focus of any Brexit deal?

Let's go back to basics.

At the start of the discussions, the Irish border was one of the three key issues EU negotiators wanted addressed before a transition period and substantive trade talks could begin.

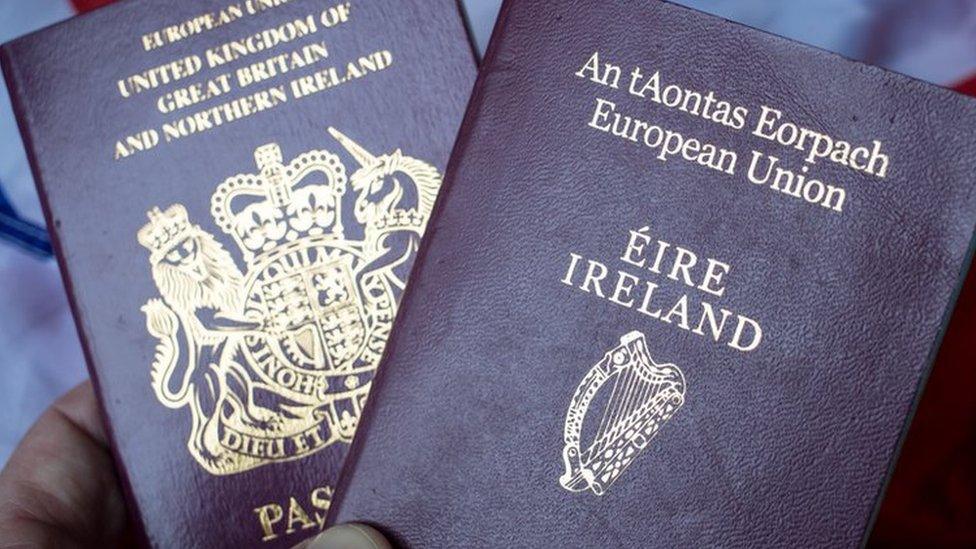

This is because after Brexit, the UK will no longer be in the EU single market and customs union: the two parts of Ireland could be in different customs and regulatory regimes, which could mean products being checked at the border.

For political reasons too, to protect progress made through the Good Friday peace agreement, neither the UK nor EU wanted to see a hard border, so in 2017 they committed to the need for a backstop.

It's a position of last resort to maintain a seamless border on the island of Ireland unless and until another solution is found.

In November 2018, after months of negotiations over how the backstop should work, the UK and EU published a draft agreement that included a backstop, external, which would see extra checks on some goods coming into Northern Ireland from Great Britain, and keep the whole of the UK in a customs union with the EU.

What will become of the Irish border when the UK leaves the European Union?

It would take effect if another solution hadn't been found by the end of the proposed transition period in December 2020.

But not everyone was happy.

Brexiteers, including the DUP, were outraged on two fronts. First, they claimed it posed a risk to the integrity of the union by creating an "Irish Sea border", and secondly, that it tied the UK to EU rules indefinitely with no say in them.

They vowed to vote down the Brexit deal unless the backstop was removed from the withdrawal agreement - and followed through on this in January, when the government suffered one of the biggest defeats in modern times on the deal.

Theresa May promised to get changes to the backstop, but it is still not clear what she might achieve.

What's the DUP view now?

It hasn't really budged.

The DUP has previously said it wants one of three things: the removal of the backstop from the deal; a time-limit to the backstop or a unilateral exit clause from it.

Last week, the party's Brexit spokesman, Sammy Wilson, said the DUP could back a deal with a time-limited backstop, because it would effectively remove it.

This gets to the crux of why the EU has refused to consider a time-limit, or anything that would put an end to the backstop, without another solution in place.

Whatever Attorney General Geoffrey Cox negotiates, the DUP will be keen to scrutinise it carefully.

Its deputy leader, Nigel Dodds, is one of eight pro-Brexit lawyers who have set out terms the deal must meet to ensure changes to the backstop are "legally binding".

But the majority of Northern Ireland's political parties - as well as a large number of business and farming groups - have repeatedly urged support for the original backstop.

It's thought that if changes are made to the backstop that can placate the DUP, many other Brexiteer MPs would then back the deal too.

Has the decision to offer more votes changed the Brexit course?

Some MPs certainly think so.

If Mrs May's deal gets voted down again, MPs get two more votes. One would be to rule out no-deal. If that is passed, then MPs would vote on whether or not to extend the exit process.

Labour's Owen Smith told BBC News NI last week that he believes, as a result of offering these votes, the PM is essentially pushing some Brexiteers into backing her deal, rather than risking a delay to Brexit.

Conservative MP Andrew Murrison, who chairs the Westminster NI Affairs Committee, also told the BBC he believed that would happen.

"Increasingly that's likely to be the case. And not just my colleagues on my side of the house but increasingly colleagues on the other side of the house as well and I think they're going to be crucial in this," he said.

Those votes will only happen if MPs reject the government's deal again.

Other political commentators and MPs believe a no-deal outcome has increased as a result of the PM's decision last week, with some Brexiteers calling to leave on World Trade Organisation (WTO) terms if the EU won't budge.

How do others rate the chances of a deal now?

That depends who you ask.

On Tuesday, the Welsh and Scottish governments demanded that Mrs May rule out a no-deal outcome, and also called for Brexit to be delayed.

Some Tory MPs who are members of Parliament's Eurosceptic European Research Group (ERG) have said they are willing to "compromise", but would rather have no-deal than a bad deal.

Whether they will do a sharp volte-face and back the deal, depends on what Number 10 can deliver from Brussels.

But the Irish government has said it still believes a no-deal outcome is unlikely.

Last week, Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Leo Varadkar said: "We are entering quite a sensitive period over the next week or two in the run-up to the next set of votes in the House of Commons on 12 March and the European Council summit which happens the week after.

"I don't want to say too much about it at this stage, but I think that the United Kingdom crashing out of the European Union without a deal on 29 March is unlikely."

What is the EU saying?

The mood music is not positive.

It's a tense time for all sides involved, and the EU has been reluctant to say much other than that it wants to provide the UK with assurances, but has stressed that the withdrawal agreement is not up for re-negotiation.

Brexit Secretary Steve Barclay headed back to Brussels on Tuesday with Geoffrey Cox in another bid to get changes.

On Wednesday, the European Commission said those talks had been difficult and still no breakthrough had emerged.

EU officials said they would work non-stop over the weekend if "acceptable" ideas were received by Friday to break the deadlock over the Irish backstop.

He said it would be able to exit the single customs territory unilaterally if it chose to do so.

But, he added, Northern Ireland would remain part of the EU's customs territory, subject to many of its rules and regulations.

Brexit Secretary Stephen Barclay accused Mr Barnier of trying "to rerun old arguments".

As of right now, there are 21 days to go until the UK is due to leave the EU.

The final act of this political drama approaches, and no-one has a clue how the plot is going to end.

- Published5 March 2019

- Published4 March 2019

- Published28 February 2019

- Published23 February 2019

- Published3 April 2019