Bloody Sunday commander Derek Wilford stands by soldiers

- Published

Lt Col Wilford: "We thought we were under attack"

As January 1972 dawned, the month forever associated with the tragedy of Bloody Sunday, Lt Col Derek Wilford commander of the 1st Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, was one of the British Army's rising stars.

He was tough, outspoken and charismatic, adored by his men whom he adored in turn.

But Wilford was no ordinary Para. He was an accomplished artist and used to read Virgil's Trojan War saga, The Aeneid, in the original Latin outside his tent.

In Belfast, where Wilford's battalion was based, the Paras had a fearsome reputation, used by General Frank Kitson, the controversial guru of counter-insurgency operations, as shock troops to deal with trouble whenever and wherever it arose.

The battalion's Support Company, consisting of some the regiment's toughest and most battle-hardened soldiers, including veterans of Aden, became known as "Kitson's Private Army".

According to Lord Saville, who conducted the 12 year inquiry into Bloody Sunday, Support Company was known for "using excessive physical violence".

Following internment without trial in August 1971, Wilford's battalion, along with other Paras, was sent to deal with serious rioting in west Belfast's Ballymurphy estate, then home to Gerry Adams, where the army had swooped to arrest and intern IRA suspects.

The operation ended with 10 people dead. Local people said the victims were all innocent civilians.

The long delayed inquest is currently being held in Belfast.

Just over five months later, Col Wilford's battalion was deployed to Londonderry to crack down on rioters, known to the army as the 'Derry Young Hooligans', who, local traders said, were ruining their business and getting ever closer to the town centre.

In response, General Robert Ford, the operational head of the army in Northern Ireland, travelled to Derry to listen to the businessmen's concerns. He was given an earful.

The situation was getting ever more serious with the result that General Ford wrote a chilling memorandum to his superior, General Sir Harry Tuzo. It said: "I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders amongst the DYH (Derry Young Hooligans) after clear warnings have been issued."

Although Ford wasn't issuing a 'shoot to kill' instruction, his words do indicate the increasingly fraught climate of the time with more soldiers and police officers now being killed after internment and the allegations of "torture" by Army interrogators that followed in its wake. "Kitson's Private Army" was called in.

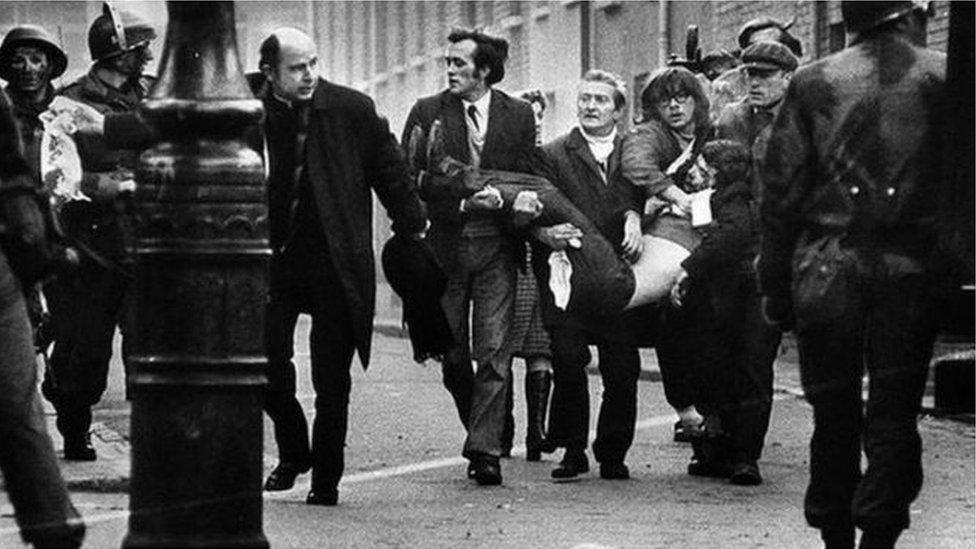

Soldiers on the ground in Derry in January 1972

Wilford had been outraged watching television images of soldiers in Derry being forced to retreat in the face of increasingly emboldened rioters.

When I interviewed him on the 20th anniversary of Bloody Sunday in 1992, he told me, "The soldiers just stood there like Aunt Sallys… I had actually said in public, my soldiers were not going to act as Aunt Sallys - ever."

With the emphasis on the "ever". Wilford was a man of his word.

Given the tensions of the time, there was a certain inevitability that trouble would break out before and during the march that had been called to protest against internment. Thousands took part.

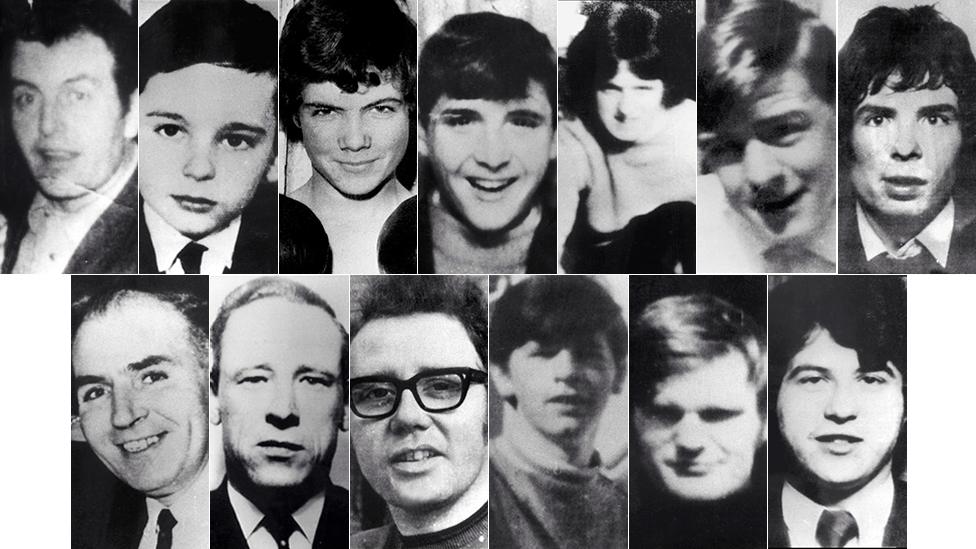

But no-one envisaged that 13 men would end up dead on what became known as Bloody Sunday.

The soldiers said they had come under attack and were returning fire.

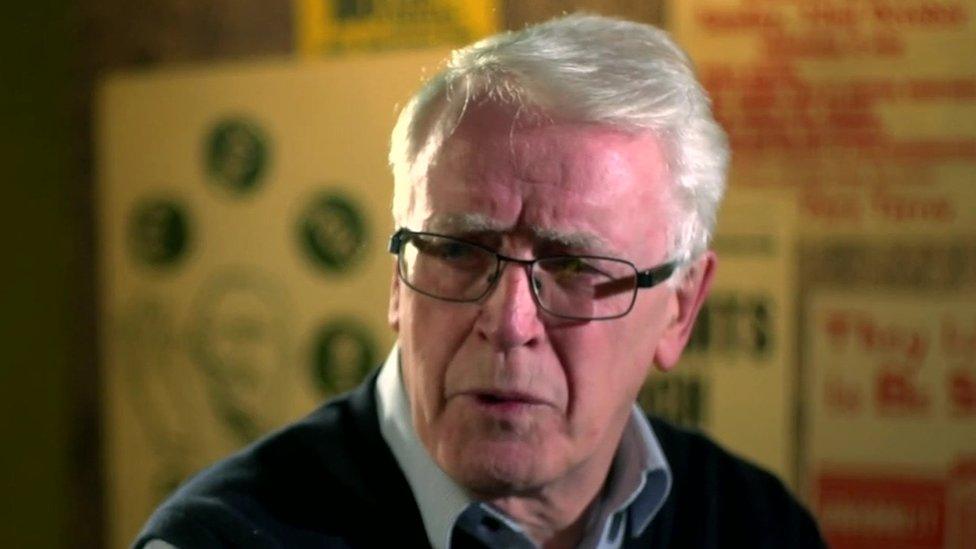

Many too were injured. Today, 47 years after the event, Derek Wilford still maintains that his men did not act improperly.

Almost a decade after the Saville Report, does he accept what the inquiry said? "No, I don't, because I was there," he said.

"We were under attack and we will actually remain convinced of that actually to the end of our days."

The victims, top row (l to r): Patrick Doherty, Gerald Donaghey, John Duddy, Hugh Gilmour, Michael Kelly, Michael McDaid and Kevin McElhinney. Bottom row : Bernard McGuigan, Gerard McKinney, William McKinney, William Nash, James Wray and John Young

In my 1992 interview, Wilford described the option soldiers faced when they came under fire.

"You can run away - certainly my battalion would never run away - take cover behind your shields or do what my battalion was trained to do, to move forward and seek out the enemy."

Lord Saville makes it clear that the first shots were fired by the Paras, wounding Damien Donaghey who, according to Saville, was not posing any threat of death or injury.

Shortly afterwards an Official IRA gunman fired a shot in their direction, it remains unclear whether that was in response to the Paras' first shots.

After Support Company invaded the nationalist Bogside enclave into which the rioters had fled, now pursued by Wilford's soldiers, a Para officer fired a warning shot.

Confusion and bloody chaos then reigned.

It is possible that the Paras thought they were then coming under attack.

Father Edward Daly who was an eye-witness on the ground, told me he saw a gunman against a wall and told him in unecclesiastical terms to get out.

In the 30 minutes following Wilford's command to "Move! Move! Move!", Support Company had fired 108 rounds and made 30 arrests.

I walked into the Bogside the following morning when the blood was still fresh on the ground and bunches of flowers had begun to appear where 13 men, young and old, had been shot dead the afternoon before.

None of them had been carrying a firearm.

I walked past the rubble of the barricade in Rossville Street in the vicinity of which six young men, mostly teenagers, were killed. One of them was John Kelly's brother, Michael, 17, who had been shot dead.

John Kelly's brother Michael was shot dead on Bloody Sunday

John Kelly and families of other victims have fought incessantly for justice, culminating in the demand that soldiers be prosecuted for the killings.

"You can't draw a line under murder," said John.

"Justice has to be seen to be done, no matter how long ago it is."

'We were betrayed'

Bloody Sunday has taken its own toll on Derek Wilford, debilitated by Parkinson's disease and age. Climbing the stairs, too narrow for his Zimmer frame, to his artist's studio, is a struggle.

The multitude of paintings in oil and watercolour, of landscapes and portraits, are testimony to his more energetic and creative days. Now he can't even hold a paintbrush.

He showed me his farewell present, a Parachute Regiment painted drum, resting on three rifle butts.

But he remains steadfastly defiant, standing by his men until the end. He is appalled at the possibility of his soldiers facing prosecution.

"I don't believe they were capable of that sort of indiscriminate shooting and killing," he said.

"We were betrayed and bringing charges against soldiers is part of that betrayal."

Would he apologise to the families of the victims? "I said that at the time and I've said it subsequently, he replied. "I see no point in repeating it because whatever I say will be discounted."

I finally asked what Bloody Sunday had done to him.

"I think it destroyed my world," he sighed.

In a far more direct way, it also destroyed the world of the families whose loved ones were killed and wounded by his soldiers.

- Published13 March 2019

- Published13 March 2019