Bloody Sunday: What next after Soldier F charged with murder?

- Published

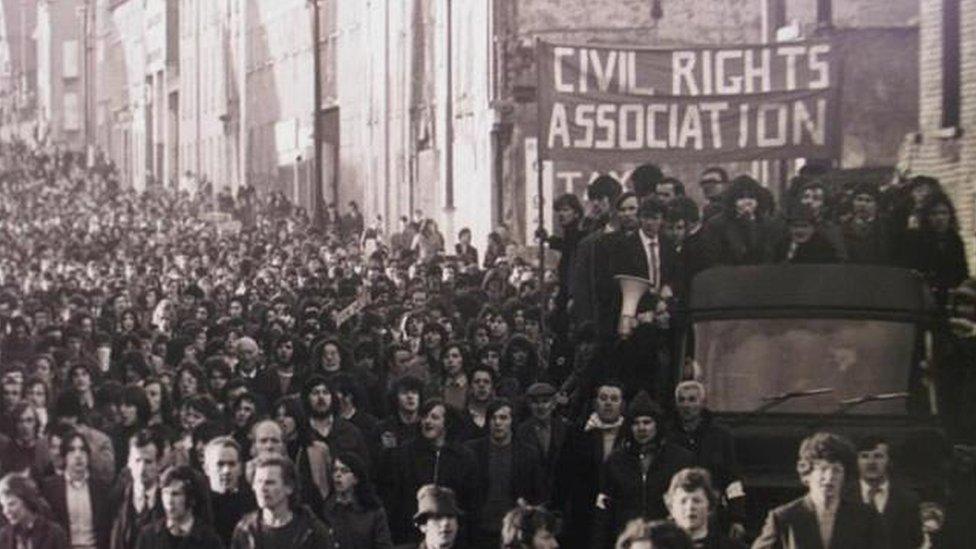

Demonstrators took part in a civil rights march through the streets of Londonderry before the shootings on 30 January 1972

On Thursday, the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) confirmed it would prosecute one former paratrooper over killings on Bloody Sunday.

The Army veteran, known only as Soldier F, is to be prosecuted for the murders of James Wray and William McKinney.

He has also been charged with four attempted murders on Bloody Sunday in Londonderry in 1972.

The sole prosecution is seen as a "terrible disappointment" by some of the families of the 13 people killed.

There are now a number questions about what will happen to Soldier F and the Bloody Sunday families following the landmark announcement by the PPS.

Were prosecutors able to rely on the testimony of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry?

No.

The long-running investigation by Lord Saville ran under the terms of the Tribunal of Evidence Act 1921.

Lord Saville chaired the Bloody Sunday inquiry, which looked into the events of 30 January 1972

As such, it was not bound by strict rules of admissibility of evidence that criminal proceedings are governed by.

So while Saville may have reached certain conclusions about the soldiers, the PPS could not rely on the same evidence for criminal proceedings - and effectively had to prove the cases afresh.

Can the families challenge decisions not to prosecute?

Yes.

All families have the right to formally request a review of a PPS decision not to prosecute.

James Wray and William McKinney were among 13 people shot dead at a civil rights march

If that independent assessment of the decision does not recommend a reversal, there are other legal options.

What next for Soldier F?

An official summons to appear before a district judge will be served.

When he receives that letter, proceedings become active.

The case will then progress through the magistrates' court before a decision is taken on whether it will be passed to the crown court for trial.

Where would a potential trial be held?

While family members might like to see Soldier F brought back to Derry to face justice, security concerns would likely prevent the trial being heard in the city's Bishop Street courthouse - a building targeted by a dissident republican car bomb earlier this year.

Dissident republicans targeted the courthouse on Derry's Bishop Street in January

Belfast Crown Court is a more realistic venue.

This is where other major Troubles related cases are held. The building is linked to a local police station, making it easier to transport high-profile defendants to court.

Will there be a jury?

This is a timely question.

For decades, any cases linked to the Troubles have been held without a jury.

A judge instead decides guilt or innocence in proceedings formerly known as Diplock trials.

However, another military veteran who is facing a conflict-related attempted murder charge - 77-year-old Dennis Hutchings - is currently challenging the decision to sit without a trial in the Supreme Court.

The judgment in that case may well impact whether Soldier F's trial will be tried by judge or jury.

Will the soldier's identity be revealed?

Anonymity orders covering 17 soldiers and two suspected Official IRA men were imposed during the Bloody Sunday inquiry and remain in place.

The decision on whether Soldier F's identity will continue to be kept from the public will be addressed during the future court proceedings.

Would Soldier F be eligible for a reduced sentence, like paramilitaries found guilty of Troubles-related offences?

Northern Ireland Secretary Karen Bradley confirmed on Wednesday that Bloody Sunday is not currently covered by legislation dealing with reduced jail terms for Troubles-related offences.

However, she noted there are plans to change the law, which were agreed five years ago.

Existing legislation only covers offences committed between 1973 and 1998 - the Bloody Sunday killings happened in 1972.

A new start date of 1968 is proposed in legislation yet to be implemented.

Could there be a future amnesty for veterans?

This remains an issue of intense controversy in Northern Ireland.

Last year, the government angered some of its own backbenchers, and Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson, when it did not include a statute of limitations on prosecutions of ex-service personnel among proposals for dealing with Northern Ireland's past.

Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson

Karen Bradley said such a measure would be unacceptable, because it would also have to cover terror suspects accused of historic crimes.

The prospect of a statute of limitations met with vocal opposition in Northern Ireland.

Both Sinn Féin and the DUP voiced concern, as did the Irish Government and representatives of victims..