Millions spent compensating wrongful convictions

- Published

More than £9m has been paid in compensation since 2010 to 16 people who have had their criminal convictions overturned in Northern Ireland.

New figures show that 84 people were wrongly convicted of crimes between 2007 and 2017.

Charges ranged from murder to rape and included people serving life sentences.

At least half of those who had their convictions overturned spent time in prison, amounting collectively to more than 100 years in custody.

The figures were obtained through a series of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests sent by BBC News NI.

One man, who spent three years in prison as a teenager for a conviction that was overturned 30 years later, has spoken about the significant impact it had on the rest of his life.

Miscarriages of justice

Cases can be referred to the Northern Ireland Court of Appeal by the Criminal Case Review Commission (CCRC).

The CCRC, which investigates wrongful convictions in the UK, was set up by the government in response to a number of high profile miscarriages of justice cases including the Birmingham Six.

It receives about 1,400 applications a year from across the UK, including about 40 from Northern Ireland.

Figures provided under FOI to BBC News NI show that a total of 84 defendants have had at least one criminal conviction overturned in the Northern Ireland Court of Appeal between 2007 and 2017.

In Northern Ireland

£9mIn compensation since 2010

84People wrongfully convicted of crimes between 2007 and 2017

30%Were sexual crimes

90% Of those wrongfully convicted were men

31Cases led to a re-trial

10Defendants were aged 16-20 when their conviction was quashed

The Northern Ireland Prison Service said it only held records for those who were found to be wrongfully convicted and spent time in custody since 2006.

The figures show that at least 46 people served prison sentences for convictions that were subsequently quashed. The longest single prison sentence served was six years.

Twelve people who had their convictions overturned were serving life sentences.

Dr Hannah Quirk is a former case review manager at the CCRC. She now lectures in criminal law at King's College London with an expertise in wrongful convictions and miscarriages of justice.

Reacting to the figures, she said: "I understand that people will be surprised as one person who is wrongfully convicted is one too many.

"But it's important to also understand what is meant by wrongful conviction.

"It would be very unusual for the Court of Appeal to say someone is innocent, instead it decides whether any new evidence has come to light that makes a conviction unsafe."

She added: "So not all these cases will necessarily be about innocence and more about if the criminal justice system applied the rules fairly at the time and whether or not if the trial happened today that the person would be convicted based on the latest available evidence."

'You go into survival mode'

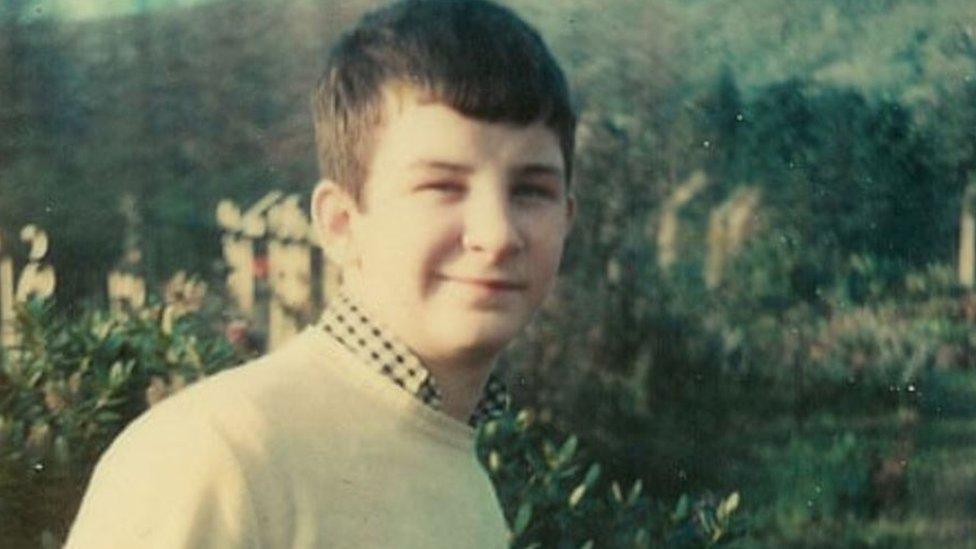

Charlie McMenamin was 16 years old in April 1978 when he was arrested and charged with a number of terrorist charges in Londonderry. He spent three years in prison.

In 2007, almost 30 years later, the Court of Appeal ruled that he was wrongly convicted and found he was in a training school on the day he was alleged to have been involved in a gun attack on soldiers in Derry's Bogside.

The Court of Appeal found evidence showing that an official at the Director of Public Prosecutions at the time told police that the charges were not to be proceeded with, but that was never passed on to the prosecuting lawyer.

Mr McMenamin said: "You have to remember I was 16 years old and I was being told by my legal people that if I fought the charges I could go to jail for 17 years.

"I was really reluctant to admit to something I hadn't done, but eventually I just give up because I didn't have faith in the justice system either way."

Mr McMenamin spent two years on remand and served a further year of his prison sentence.

Charlie McMenamin was 16 years old in April 1978

"Jail was tough, I got a lot of beatings. I felt why should I be here, so I just fought against the system.

"I was being told I was a political prisoner, but I was saying I wasn't because I was in jail for something I didn't do. So as a teenager I had all those battles going on as well, but you just go into survival mode."

He said the experience changed the course of his life.

"When I came out of jail, everything had changed, friends had moved on. I had a girlfriend, my teenage sweetheart, and in my last year in prison she died of cancer.

"Even practical things like travelling, I couldn't go to America and employment was a problem. It had huge impact on the rest of my life."

In its conclusion, the Court of Appeal said it was left with a "sense of unease" about Mr McMenamin's case.

It raised concerns about his age at the time and the fact he was denied access to a solicitor or an appropriate adult until after he had made admissions to an offence which was accepted by the prosecution he could not have committed.

"I fought the case for my family. My mother and father, who are now both deceased, had lived with it their whole lives.

"When I found out the conviction had been overturned I was actually physically sick, it was like the whole thing had left me and I was a different person."

The court service said it could not provide a breakdown of why each of the 84 criminal convictions were overturned because of the time and cost involved in a manual trawl of individual judgments.

Deputy director of the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Daniel Holder said there was a public interest in finding out more about why convictions were overturned.

He said: "I am surprised that this exercise has not been undertaken in order to identify and remedy any emergent patterns.

"One of the alarming issues from the legacy of our past is the circumstance where information is withheld from prosecutors and the courts to provide cover for the activities of paramilitary informants, who themselves were allowed to operate outside of the law."

Those who have had convictions overturned can apply for compensation.

The Department of Justice in Northern Ireland has had responsibility for compensation since the devolution of policing and justice in April 2010.

Compensation is calculated by independent assessors who look at what the person was convicted of, what the punishment was and what consequences it had on the person's life and whether they had a criminal record before.

The Department of Justice said when considering an appeal for compensation for a criminal conviction there must have been grounds to support the appeal decision that a person experienced a "miscarriage of justice".

- Published30 May 2018