Stormont talks: Is there hope for political breakthrough?

- Published

Attention has again turned to Stormont, where talks are taking place in a push to restore the political institutions

On a dull and wet morning last Tuesday, journalists gathered in their usual spot in the Stormont estate, waiting for soundbites from the Northern Ireland political parties.

The reason?

A new round of talks was starting to try and kickstart the assembly, which has been sitting dormant for more than two years after a row between the main power-sharing parties.

But new discussions bring with them a big disclaimer: if several rounds of talks since January 2017 haven't achieved anything, why should it be any different this time?

It's a fair question.

Journalists covering the political beat have gotten used to hearing the same catchphrases from the parties each time talks have started.

And there's been no indication that they are prepared to budge from their red lines this time.

A source says they do not see a willingness for a deal in spite of the attention on the politicians

That being said, there are a couple of reasons that make the latest process marginally different from what we've become accustomed to seeing.

The first is the impact of the murder of journalist Lyra McKee in Londonderry last month.

'On best behaviour'

While there were always going to be talks again after the council elections, the public ire in the aftermath of the murder - and the direct plea from a priest at Ms McKee's funeral to the politicians - set the tone for the process.

A source involved in the new talks said the parties were being on their "best behaviour" so far but warned that it was far too early to start getting hopes up.

"I don't sense a willingness to do what needs to be done," they told me.

On Tuesday, we also learned of the structure that the UK and Irish governments have set out for the coming weeks.

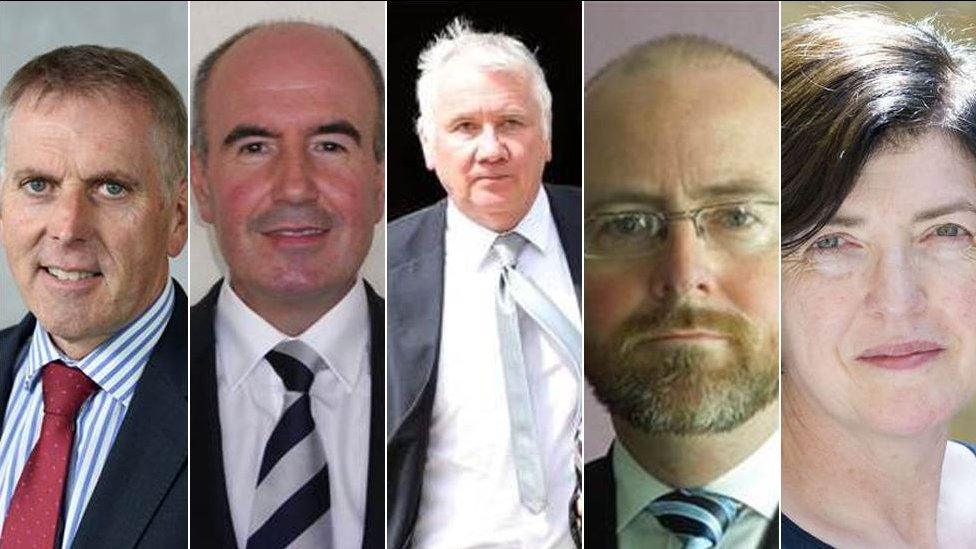

The working groups will be led by (from left): David Sterling; Paul Sweeney; Sir Malcolm McKibbin; Hugh Widdis and Sue Gray

It's a two-pronged approach: weekly roundtables involving all the party leaders alongside five working groups that will deal with specific issues relating to the deadlock and future of Stormont.

The groups are being chaired not by political officials but former and current senior civil servants.

Among them are Sir Malcolm McKibbin, the former head of the Northern Ireland civil service, and Sue Gray, an extremely powerful civil servant who previously held a top job in Whitehall.

For Sir Malcolm's part, he has previous experience in Stormont negotiations, working with the parties in summer 2017, not long after the assembly collapsed.

The working groups, made up of three representatives from each party, have officially held their first meetings but it's not clear how effective they'll be in the short term.

Brexit ramifications simmering

Will the civil servants take charge and get the parties down to work? And how will the politicians deal with each other?

The talks source told me: "You won't know if it's serious until after the election."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The European election takes place on 23 May.

With all the main parties battling it out at the ballot box for another two weeks, it seems unlikely that there will be anything to report from Stormont until after the election at least.

And Brexit and its ramifications are still simmering away in the background.

There is a theory as to why the UK and Irish governments have not placed any firm deadlines on the process yet.

The DUP addressed the media in Parliament Buildings after talks began last week

In the past, fixed deadlines have been missed and privately some in government feel putting a firm date on the talks will just harden minds, as opposed to softening stances that have developed over the past two years.

Instead, all the two governments have said is that they will review progress at the end of May.

Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney has repeated his view that he thinks there can be progress "within weeks, not months".

That might be feasible if it wasn't for the fact that it's not just the issues dividing the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin that need to be resolved.

As I have written before, time away from Stormont has not been a healer.

Trust between the parties has broken down and if the assembly is to function properly again relationships need to be repaired too.

Northern Ireland's politicians have surprised the public before by achieving compromise when it looked impossible.

Many hope they will now do it again.

But it's a question of how and when.

- Published10 May 2019

- Published8 May 2019

- Published7 May 2019