Contaminated blood inquiry: 'Infection has ruined my life'

- Published

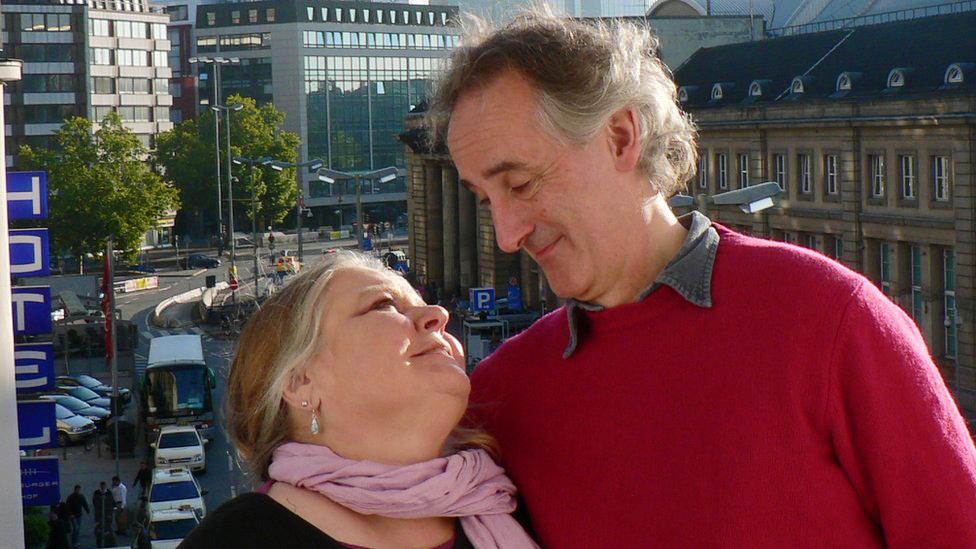

Marie Cromie says a contaminated blood transfusion "ruined my life"

A Belfast woman has said her life was ruined after she was given infected blood in a transfusion.

Marie Cromie found out she had hepatitis C in 2005 and has had to have two liver transplants.

She spoke ahead of the public inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal starting to hear evidence from people in Northern Ireland on Tuesday.

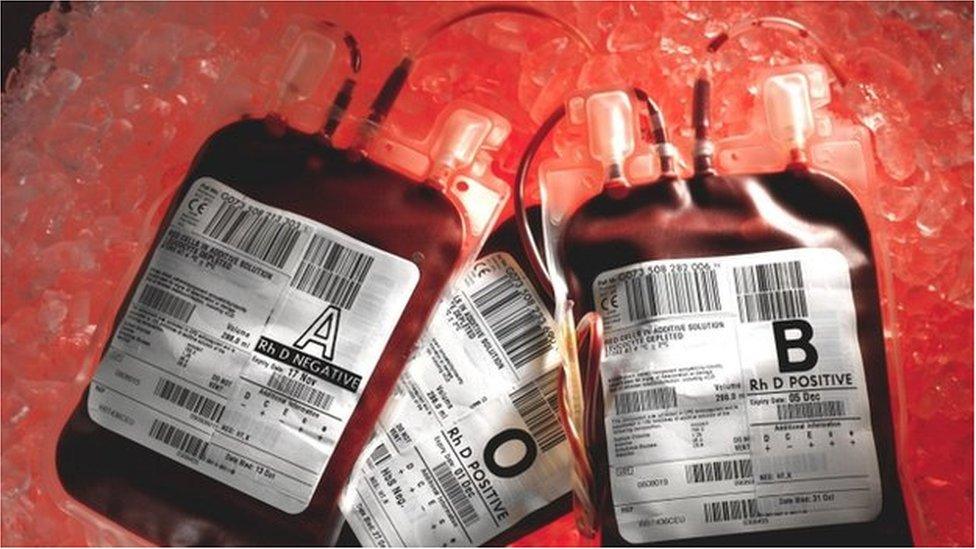

Thousands are believed to have been infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses through contaminated blood products.

Others who had blood transfusions after surgery in the 1970s and 1980s were also exposed to contaminated blood.

Speaking to BBC News NI, Ms Cromie described her shock and anger at being told she was infected and said it "took away part of my life with my children, with my grandchildren".

The public inquiry into contaminated blood arrives in Northern Ireland on Tuesday

Meanwhile, a letter has been sent by party leaders and senior MPs to the prime minister, calling for compensation.

Among those who signed it are Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, Liberal Democrat leader Vince Cable and Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) MP Nigel Dodds.

'Turned upside down'

The public inquiry will hear evidence in the Waterfront Hall in Belfast over four days.

Some of the Northern Ireland victims and their families will give evidence - among them will be Mrs Cromie's daughter Danielle Mullan.

Mrs Mullan said the family's world had been "turned upside down" by the diagnosis.

She said: "It was really hard because I was no longer a daughter, I was more a carer to my mum."

She said that as the years went on it became harder as she saw the complications her mother was having to endure.

Mrs Cromie has traced the hepatitis back to a blood transfusion she had to have when her son was born in 1981.

Until she began to feel very unwell in 2005, she was unaware she had been infected.

After testing, a consultant told her she had hepatitis C, that it had already begun to affect her liver and that she would eventually need a transplant.

She has since undergone two transplants, the second of which took place in 2015 at King's College Hospital in London.

Saying goodbye

Mrs Cromie described being at "death's door" waiting for a suitable liver and said it was "horrible" having to say goodbye to Mrs Mullan in Belfast's Royal Victoria Hospital.

She said: "I just looked at her and thought: 'I mightn't see you again.'"

Marie Cromie has had two liver transplants

The problem dates back to the 1970s when blood-clotting products imported from the US caused some patients to be infected with HIV and hepatitis.

That is because some of the human blood plasma used to make the products came from donors such as prisoners and prostitutes, who sold their blood.

The blood products were made by pooling plasma from up to 40,000 donors and concentrating it.

Warnings were raised as early as 1974.

Eight years later as the Aids crisis unfolded, the Department of Health in Westminster received expert advice that they should be withdrawn but that was not heeded until 1986.

Families want to know why and who within the NHS and the government knew what and when.

Vomiting up blood

For Mrs Mullan, the seriousness of her mother's condition became clear after a particularly frightening incident when she began to vomit up blood at home.

She said: "I went into the bedroom and turned on the light and there was just gallons of blood. Blood after blood. It just kept coming up, wouldn't stop.

"We phoned for an ambulance, got her to the hospital.

"They told us it was touch and go for the night and that for me was when it really hit home."

Danielle Mullan will give evidence to the inquiry

She said at that moment she realised her mother was battling something "way beyond" a normal infection.

The public inquiry into what's been called the "biggest treatment scandal in NHS history" was announced in 2017.

The first witness evidence began to be heard in London in April 2019.

'Take responsibility'

Both women said they would like answers and for someone to take responsibility.

Mrs Cromie said: "Why did somebody take the decision to buy infected blood? To take infected blood from America, from prisoners, drug addicts and give it to us innocent people who needed the blood?"

Mrs Mullan said she would also like better understanding.

She said: "I want to kill the stigma that comes with the disease, so many people over the years, you mention the word hepatitis and automatically people think - they must have been a drug user, they were an alcoholic.

"That's not the case, my mum and all the people who were involved in this inquiry were victims in this.

Derek Martindale's brother was also infected with HIV: "He knew he was dying... I wasn't there for him"

For Mrs Cromie, the public inquiry hearings in Belfast are another step on a long road.

She said: "At the start when I got it I was told by a couple of nurses, hepatitis nurses, not to tell too many people.

"I just had to say: 'Oh I caught a virus.'

"That's what I said instead of being able to say: 'I got hepatitis C through infected blood.'"

"But now, I will say to people when they say about, you know, your transplants and things, I say: 'Yeah I got it through contaminated blood.'

"And my husband says the same to people. Through no fault of my own, I got it."

- Published30 April 2019

- Published24 September 2018

- Published30 April 2019