Autism: Mandatory training for all NI teachers 'premature'

- Published

The Department of Education (DE) is not yet in a position to introduce mandatory autism training for teachers.

Autism NI has called for the move due to the significant increase in autistic pupils in Northern Ireland's schools.

DE said making the training mandatory would be "premature".

A DE spokesman said officials were engaging with initial teacher education providers and the Education Authority on current training provision, with a view to identifying any gaps.

However, the chief executive of Autism NI, Kerry Boyd, said mandatory training would benefit both teachers and pupils.

"It's something that the teachers are saying needs to be done, and our parents are saying it," she said.

Kerry Boyd from Autism NI

"We hope that it'll provide a culture of change within schools and within society for better autism awareness.

"More and more of our children are being diagnosed and this is something that needs to be done to ensure they get the best educational outcomes."

Department of Health figures have shown that the proportion of school-age children with autism has almost trebled in a decade.

That has led some parents to say they have to battle to get appropriate support for their children.

'Under the radar'

In Northern Ireland, school-age boys are three times more likely to be diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) than girls.

Recent scientific studies have suggested many autistic girls and women go undiagnosed.

That echoes the experience of Gillian O'Hagan, an experienced special educational needs co-ordinator (SENCO) at Aquinas Grammar School in Belfast.

She told BBC News NI that girls were often thought to be shy, depressed or anxious rather than having ASD.

"For the boys, it's more overt and we can catch that earlier but for the girls it can go under the radar," she told BBC News NI.

"Girls appear to have anxiety disorders or mood disorders - actually what you then find out is that there is a primary underlying diagnosis of ASD there.

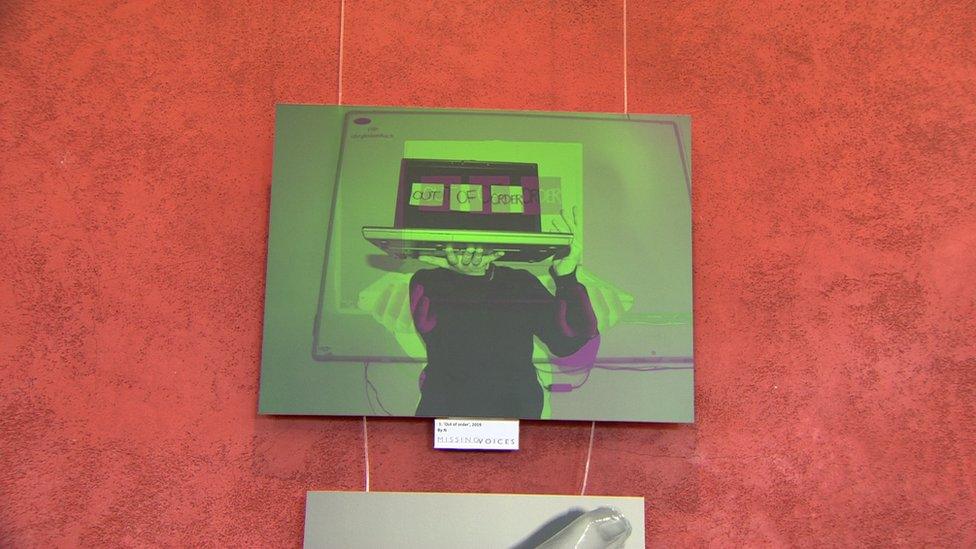

The Missing Voice project gave nine teenage girls with ASD the chance to tell the story of their lives in mainstream education

"If we had known that all along, or were able to target that from when they had transitioned from primary into post-primary, you might find that the anxiety or mood disorder wouldn't have had progressed."

To help some girls with ASD to express themselves, she runs a project to enable them to tell the story of their lives in mainstream education.

Nine teenage girls from four Belfast post-primary schools were taught photography as part of the Missing Voices project, which culminated in an exhibition of their work at Stormont.

Ms O'Hagan said it showed the difference that targeted help for small groups of pupils could make.

"It can often be hard to articulate how you're feeling, especially if you're challenged by ASD," she said.

Art from the Missing Voices exhibition

"The use of photographs provided a stimulus around which we talked and I couldn't get them to stop talking when they were telling me what was in their photographs."

Olivia McCambridge, 19, said the photography classes made it easier to convey how she felt.

"It gave us a chance to speak," she said.

"Talking to someone about your experiences is not easy but if you have a visual to point at, it makes it so much easier."

Olivia McCambridge said the Missing Voice project gave her 'a chance to speak'

She added: "The social landscape is definitely the most poignant challenge in school.

"Academically I never had too much trouble, but socially it seems like everyone has been to this class but you just happened to miss out so you want to be taught how to be social."

Having left school last year, Ms McCambridge has just completed her first year at Queen's University and has high ambitions for the future.

"My hope is to go on to do a PhD at university with some kind of astrophysics research," she said.

- Published8 July 2019

- Published10 May 2019

- Published21 February 2019