Harland and Wolff: The troubled history of Belfast's shipyard

- Published

HMS Eagle, an aircraft carrier built by Harland and Wolff, was launched by the Queen in 1946

Famous for building the Titantic, the Belfast shipyard was founded in 1861 by Yorkshireman Edward Harland and his German business partner, Gustav Wolff.

By the early 20th Century, Harland and Wolff dominated global shipbuilding and had become the most prolific builder of ocean liners in the world.

The firm survived two world wars; the partition of Ireland; the Troubles and the sinking of its most famous product.

But it has also faced longstanding financial problems and over the decades about £1bn of taxpayers' money has been pumped into Harland and Wolff to keep it afloat.

The Belfast shipyard has huge cultural and historical significance.

It was once one of Northern Ireland's biggest employers and the engine room of its economy.

The workforce reached a peak of about 35,000 people, but now on the brink of insolvency, about 120 staff face losing their jobs.

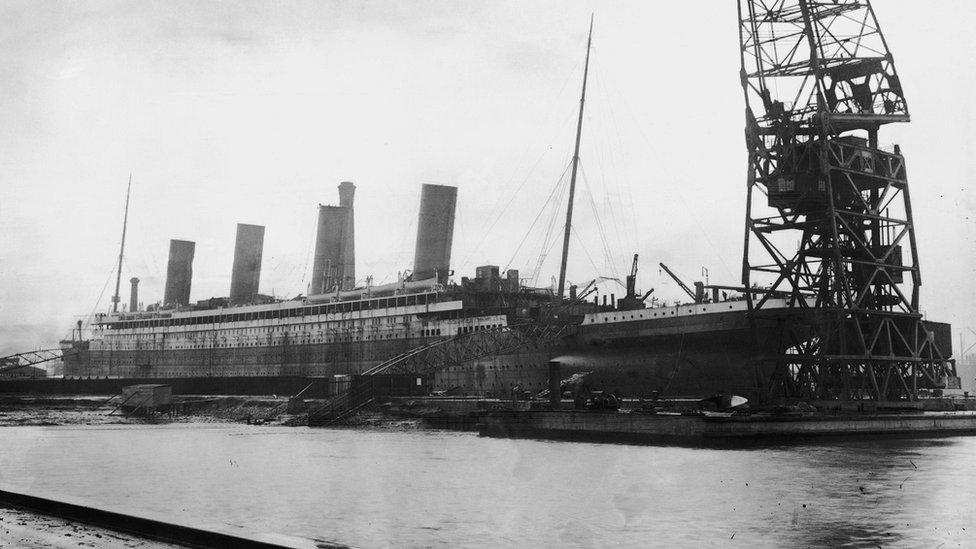

The Titanic in dry dock at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in February 1912

Pride and nostalgia for the shipyard extends beyond its industrial heritage or past commercial success.

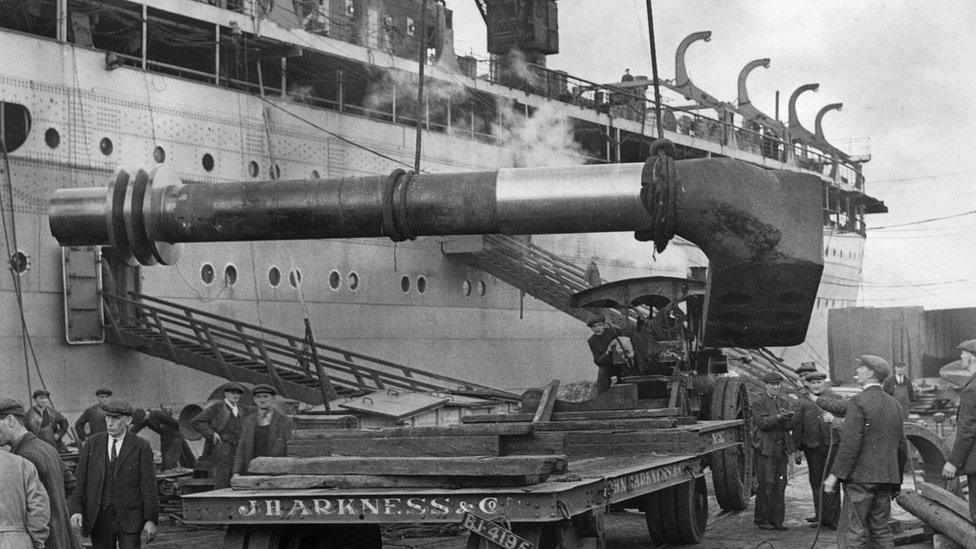

It was an important UK asset during World War Two, producing 140 warships, 123 merchant ships and more than 500 tanks.

"When you think that Harland and Wolff holds the record for ship production in World War Two, it proves that we did do our bit," says former shipyard worker and author, Tom McCluskie.

The shipyard's contribution to the British war effort also made Belfast docks a key target for German bombers.

About 1,000 people were killed during the Belfast Blitz of 1941, with Harland and Wolff among the buildings that were hit by the Luftwaffe.

Nationalisation

The workforce peaked in the post-war years, but by the late 1950s, the yard was facing increased global competition and the impact of the rise of air travel.

The launch of the Canberra in 1960 marked the last cruise liner to be built in Belfast, and by the middle of the decade, the business was in serious decline.

The Canberra was built for P&O to sail between London and Sydney

At one stage in 1966, the management went to the old Stormont government and pleaded for a subsidy because it did not have enough money to cover the next pay day.

That was the start of more than 30 years of subsidies.

The firm was nationalised in 1975 with the Northern Ireland Office minister Stan Orme describing the business as having "a sorry financial record".

By that stage it was still employing about 10,000 people.

It returned to private ownership in 1989 through a management-employee buyout, backed by the Norwegian industrialist Fred Olsen.

The shipyard increasingly focused on the oil and gas sectors, but struggled to compete against major shipbuilders in east Asia.

Harland and Wolff has also been badly scarred by sectarianism.

The firm's workforce was overwhelmingly Protestant and some Catholic staff were subjected to insults, threats and even physical attacks.

A 1970s BBC report focused on complaints of sectarianism by Catholic shipyard staff

Shortly after the partition of Ireland in 1921, sectarian riots erupted on the streets of Belfast and some of it spilled over into the workplace.

"In the shipyards, there were cases of men being thrown into the dock and pelted with sawn-off rivets - Belfast confetti," said one archive news report.

Fifty years later, as the Troubles took hold in Northern Ireland, Catholic workers complained of intimidation inside the shipyard.

Another worker said a colleague asked if he was a Protestant and when he said no, he was ordered out of the shipyard by a gunman.

In the 1970s, a Catholic shipyard worker said his Protestant colleagues threatened him with a gun

When he refused to leave, he described how another colleague moved towards him, showing the "butt of a revolver," at which point the Catholic worker left the yard.

The sectarian strife inside Harland and Wolff "reflected what was going on in society," according to retired trade unionist Tom Gillen.

He adds that the firm's management was "slow at addressing community difficulties".

The Stirling Castle was built in Belfast in 1935

The yard built its last ship in 2003 - a Ministry of Defence ferry called the Anvil Point.

Since then it has worked on other areas of marine engineering such as oil rig refurbishment and offshore wind turbines.

Later on Tuesday, an insolvency request is expected to be filed at the High Court in Belfast, marking the end of a chapter of the city's industrial heritage.

However, staff at the yard are still calling for government intervention and have vowed to stay on site and continue their protest.

- Published5 August 2019

- Published30 July 2019