The Troubles: Does South Africa hold lessons for Northern Ireland?

- Published

A peace wall that divides communities in Belfast

I arrive in Belfast on a chilly morning. I had spent many sleepless nights reading and preparing for the trip to Northern Ireland.

Everyone I'd talked to about what to expect had spoken about the peace lines - physical walls keeping two communities apart.

"There is nothing like it," a colleague who grew up in Belfast had told me.

Growing up in South Africa, segregation was stark, but even I'd never seen anything like it.

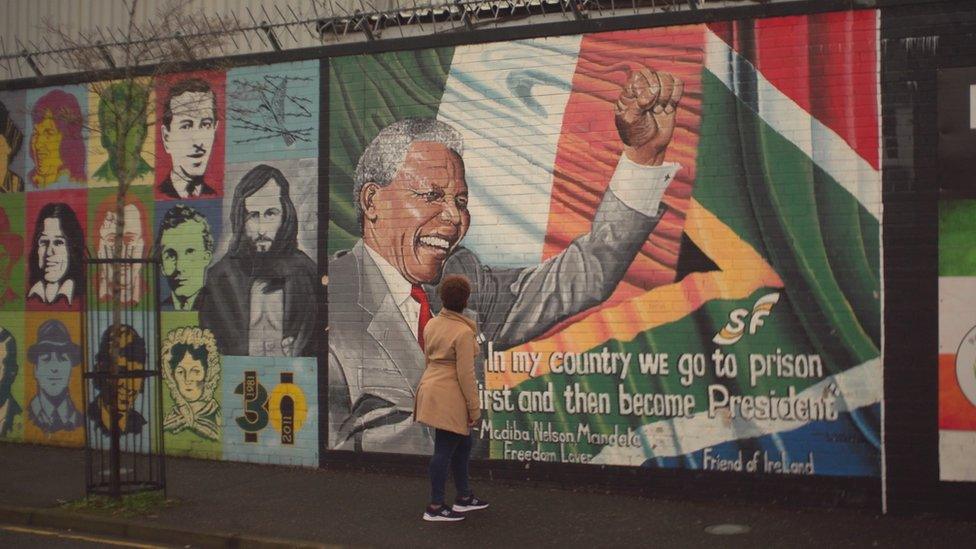

On Divis Street, one wall painted with murals, mostly political, included the face of my first black president, Nelson Mandela.

These seemingly demarcated areas reminded me of apartheid South Africa in a time of police curfews where there were spaces only whites were allowed and black people didn't dare wander.

This meant minimum to no interaction between races at most times, something the apartheid system thrived under.

It struck me as odd that here, in first-world Europe, these divisions still existed.

'Something felt broken'

Up ahead stood a large metal gate, which someone opened each morning and shut at night.

This unsettled me: I come from a broken society, and something felt broken here.

In South Africa, there is a common narrative - apartheid was wrong and black people were the victims.

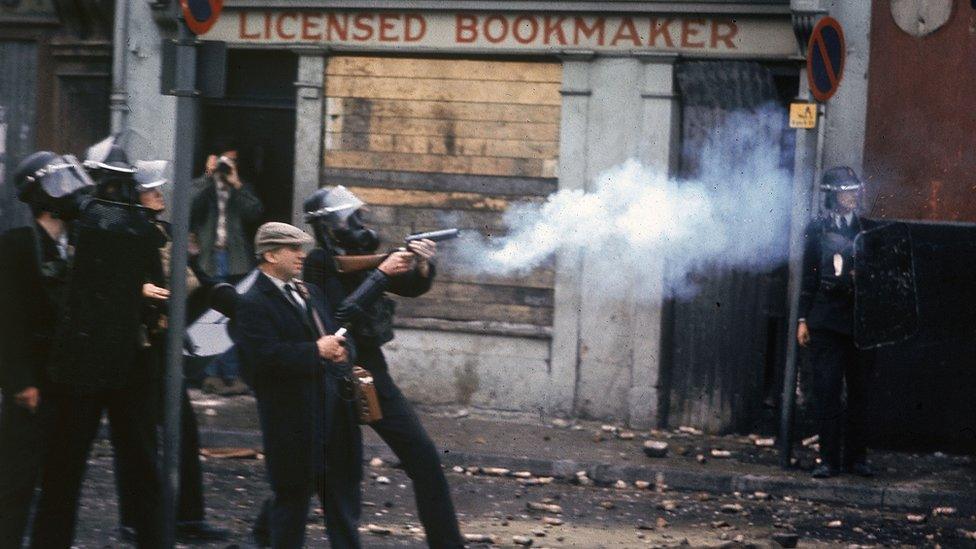

Alan Bracknell, whose father was killed in a gun and bomb attack more than 40 years ago, told me a common narrative does not exist in Northern Ireland.

He was seven years old when his father was killed in a bar during a family celebration.

"There is an ongoing debate as to the definition of a victim here," he said.

"There are so many different narratives out there but if we can get an understanding of how violence affected people, how people had to live through that violence, then we can get to a stage of acknowledging what we've done to each other."

Truth and Reconciliation

As part of healing, and perhaps even acknowledging the horrors of our history, South Africa had the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

It was an opportunity for victim and perpetrator to come face-to-face, speak openly about what had happened and perhaps even find forgiveness.

South Africans have been urged to embrace a national identity

There was once talk of a similar exercise for Northern Ireland after the signing of the peace agreement.

The people I met believe there is simply no political will to see this through.

Our TRC process was not without its flaws.

Even today, some question whether more should have been done, whether instead of confessions, families should have demanded justice.

In fact, some now are trying to lay criminal charges against known operatives of the apartheid government.

But one thing that many agree on is the process itself.

The roots of Northern Ireland’s Troubles lie deep in Irish history

It made it possible to hold a mirror to ourselves, it brought to the surface how deeply broken our society was, how scarred we were - and still are - by the violence.

Prof Brandon Hamber, an expert on post-conflict transition, was involved in reconciliation efforts in both South Africa and Northern Ireland.

"I don't think you can really rebuild relationships in a society if people are not interacting with each other in an ordinary way," he said.

But how do you make reconciliation work?

"Reconciliation for me is a contested idea," he said.

"It's not getting everybody together and saying we all agree on this great future.

"It's more that we agree to share the space. So how are we going to live with each other?"

You may also be interested in:

Have efforts at integration been enough? Some communities in Northern Ireland remain polarised.

This is evident even in the schools, most of which are segregated.

I visited two schools in Londonderry - one with many Protestant pupils, the other a Catholic school - separated by a river and a peace bridge.

The bridge was meant to be a gesture of connecting the two communities, but has it worked?

Pupils on both sides tell me they hardly ever go to "the other side".

And there, listening to young people, my heart ached. They had not lived through the Troubles but had inherited the idea of "us" and "them".

There have been a few incidents of unrest in recent months in places such as Derry.

"It's like the fear of the unknown," said 18-year-old Laura McFadden. "We all live in different areas."

One of the biggest things the leaders in South Africa advocated during the transition into democracy was embracing a national identity, that you cannot build a people without a common identity, we would need to be South African first.

In Northern Ireland, there is no consensus on national identity.

At the Catholic school, the group of pupils I spoke to identified instinctively as Irish, while at the other school the pupils told me they were British.

"There is still bitterness from older generations, and that is something that still trickles down," said pupil William Watson.

"We were born after the peace agreement so we don't really know the brunt of what happened.

"We can read it in a text book but it's never the same.

"The tensions don't have to be there."

Fireworks over the Peace Bridge in Derry on New Year's Eve 2013

But how do you overcome those tensions?

Maybe speaking about them openly is the first place, something South Africans have learnt to do.

The violence has diminished, but neither society has the luxury of forgetting about the past.

Of course, any kind of South Africa-style TRC would require political consensus, something that may not be easy to get.

I'm reminded that peace is a fragile thing.

- Published13 August 2019

- Published12 August 2019

- Published8 June 2018