Troubles trauma - the hidden legacy of violence

- Published

The Agreement Generation - What do they think?

Half a century ago, life in Northern Ireland took on a grim new normality.

The dreadful rhythm of murders and maimings continued for three decades, with the conflict largely ending in the late 1990s.

But while the worst of the Troubles may feel more distant with each passing year the legacy of trauma is very current.

Denise Mullan is one of thousands of people living with it.

Her father Denis was shot dead by loyalists at their family home near Moy in County Tyrone in 1975.

Many of those experiencing mental health problems today were children during the Troubles

She was four years old but describes her memories in detail.

She remembers clay balls, which the gunmen threw at the house before they attacked, "sliding down the wall".

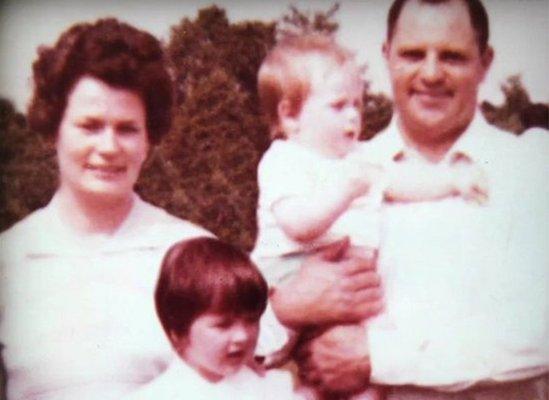

Denis Mullan's wife, son and daughter Denise were close to him when he was killed in 1975

She recalls her mother, who was also fired upon a number of times, "going out through the kitchen window".

She went to look in on her younger brother, who was 13 months old at the time, in his cot.

Then she went back to her father and stayed with him for, she now knows, two hours.

"My nightdress was covered in his blood," she recounts.

'Feel like you've been beaten'

A form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) means a certain smell - which reminds her of the night her father was murdered - brings back memories, suddenly and terribly.

"I can't exactly describe to you what it's like," she says.

"But whenever that smell comes over me, I take the shakes. My legs become weak. My mind becomes blank.

"It can pass within a few seconds or minutes. But for the rest of the day you just feel you've been beaten black and blue."

Denise Mullan was four years old when she witnessed the murder of her father

PTSD affects different people in various ways.

Researchers have found the condition is particularly common in Northern Ireland.

An Ulster University study in 2011 found that 8.8% of people had met the criteria for PTSD at some point.

Academics said that was ahead of the rate in other post-conflict societies.

Siobhan O'Neill, who is professor of mental health sciences at the university, says: "The difference here is that people here weren't offered support and services.

"We didn't screen for PTSD, so there is a lot of hidden post-traumatic stress disorder."

Other figures she and her fellow researchers have published are just as sobering.

Prof O'Neill says that contributes to a high suicide rate: "Our male rate is twice that of England."

She also points out that in spite of the fact that the prevalence of mental illness is highest in the UK funding for mental health is significantly lower compared with other regions.

"It isn't until relatively recently that we've realised the mental health needs of this population," she says.

"Until five or 10 years ago, people weren't really coming forward and asking for help.

"But there's been a huge shift in that.

"People are asking for help and we're finding services are struggling with the demand because of the lack of investment in this area."

'Poured us brandy and sent us away'

Mental health has become a much more public issue since the height of the conflict.

Denise Mullan remembers that people "hadn't even heard of counselling in the 1970s and 1980s".

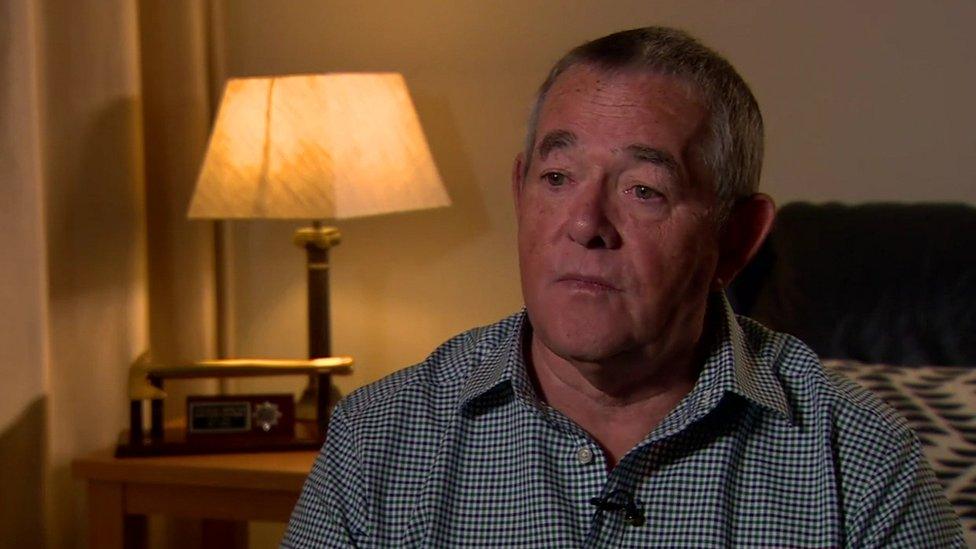

Many people are living with "hidden post-traumatic stress disorder", says Prof Siobhan O'Neill

Of the many thousands of people who witnessed appalling scenes, members of the emergency services were particularly exposed.

Retired firefighter Bob Pollock recounts that after he and some colleagues were caught up in a bombing in the early 1970s, a senior officer "poured us a brandy each, then said: 'Away you go.'"

Such stories are common among those who were on the frontline, responding to tragedies.

Bob says he is thankful he has not suffered major psychological distress as a result of his experiences.

But he is aware that his generation may only have started to consider their long-term mental health after they retired.

"Post-traumatic stress can come on many years down the line - people can suppress it," he says.

"When you're in the job you have other things going on.

"But when you're coming out of the job you have time to think about things like: 'Was I really that close to that?'"

As a firefighter, Bob Pollock dealt with many major incidents in the Troubles

As awareness of mental health has risen and issues that were once taboo are talked about more, many from the generation that lived through the Troubles are seeking out help for the first time.

Alan McBride, the co-ordinator of the Wave Trauma Centre, says Troubles anniversaries tend to bring an influx of people asking for help.

"We never really escape our Troubles here," he says.

'Toxic enviornment for children'

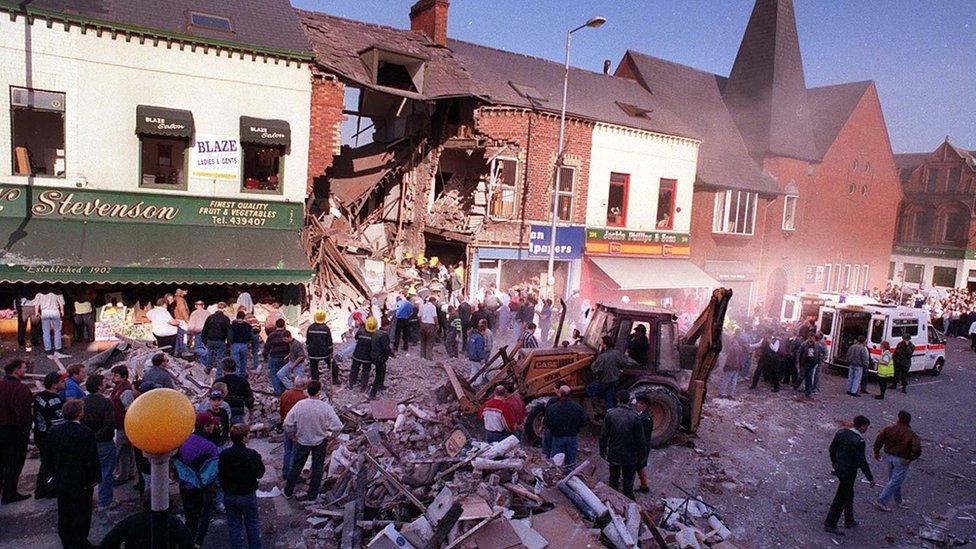

Alan, whose wife Sharon was one of nine civilians killed in the IRA Shankill bombing in 1993, has "no doubt" that people in certain areas of high deprivation feel "left behind" by the peace process and are particularly feeling the legacy of mental health problems.

"In Northern Ireland, there's a shortage of counsellors and a shortage of resources," he says.

"The waiting list at Wave is four months."

Experts are becoming more concerned that young people, who were not even born when the conflict was going on, are now feeling the effect too - so-called "trans-generational trauma".

Alan McBride's wife Sharon was one of 10 people who died when an IRA bomb exploded on Belfast's Shankill Road

Prof O'Neill explains: "Children who have parents with mental health issues are more likely to have mental health problems themselves.

"It's also about the legacy of the conflict in some communities.

"There is unemployment, drug use and low educational attainment.

"All of these things can come together to create an environment which is toxic for a child."

She believes there needs to be a greater focus on funding for measures to prevent mental illness.

"We know if we can intervene early, we can prevent the long-term damage to children's health and life chances as they grow into adulthood."

You may also be interested in:

The worst years of the Troubles are receding further into the past but the impact of the conflict remains very present.

Denise Mullan began to go to counselling last year, she says, after her mother "hit the wall" as a result of the trauma she suffered.

She told me: "There are many weeks when it pains me to go.

"But I know I have to continue with it because in 20 or 30 years, I don't want to hit the wall."

She strongly believes the mental health consequences of the Troubles must be addressed for the sake of the future.

"This is how Northern Ireland will move on.

"There are so many victims out there who need help and understanding."

- Published26 January 2018

- Published4 February 2016