Q&A: How does the border plan differ from the backstop?

- Published

How does the prime minister's Irish border plan differ from the backstop? BBC News NI's economic and business editor John Campbell has a look.

The backstop - remind us?

It was the plan for keeping the Irish border as open as it is today, if that can't be achieved through a trade deal or technological solutions.

It was agreed by the former Prime Minister Theresa May in November 2018.

It would mean the whole of the UK staying in a customs union with the EU.

Northern Ireland alone would stay in EU's single market for goods.

This arrangement would remain until both sides agreed there was something better to replace it.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson opposes the backstop saying it is antidemocratic and could trap the UK in the EU's customs territory

PM: Boris Johnson: "It (no deal) is not an outcome we want... but is an outcome for which we are ready"

How does his plan differ on customs?

It says the whole of the UK should leave the EU's customs union.

This inevitably means a new customs border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland with new requirements for cross-border traders.

However the prime minister believes the impact of this can be minimised with any checks taking place away from the border.

His plan involves trusted trader schemes and simplified customs procedures with the smallest traders being exempt from all customs procedures.

He suggests that physical checks would only be required on a small proportion of trade and that most checks could take place at traders' premises.

However the plan suggests that checks may also have to happen at "other designated locations which could be located anywhere in Ireland or Northern Ireland."

Are those 'designated locations' customs posts by another name?

The plan would also probably require the EU to make changes or derogations to its customs rules.

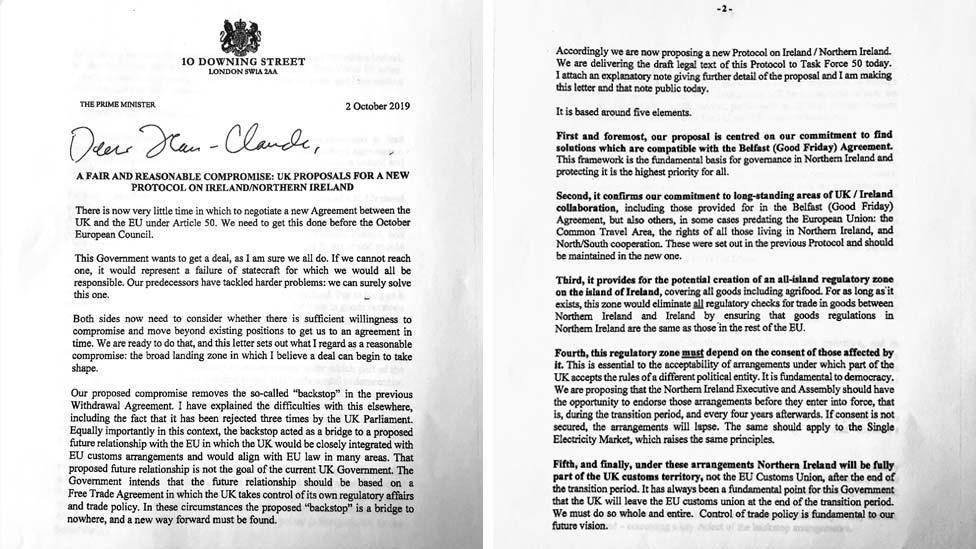

Mr Johnson has written to the European Commission president about his proposals

And what about single market rules?

Mr Johnson's plan has big similarities to the backstop.

Northern Ireland would continue to follow EU rules on agriculture, food safety and industrial goods -the rest of the UK would not.

That would effectively mean a new border in the Irish Sea with checks on goods coming in here from other parts of the UK.

These sorts of checks already happen on livestock.

All animals coming here from the rest of UK enter through an inspection post at Larne Harbour.

The new plan would mean an increase in the scope and scale of these checks.

The DUP has welcomed the new border plan

What about Stormont?

One big difference in the new plan is that the Northern Ireland Executive and Assembly would have to approve that single market arrangement coming into force.

Then every four years, Stormont would have to decide if it wants to continue to follow EU rules or align with the rest of the UK.

The DUP, which has welcomed the plan, believes that would mean Northern Ireland would always default to UK regulations unless there is a cross-community vote at Stormont to continue to follow EU regulations.

Nationalist parties fear this would amount to a unionist veto on whether to continue to follow EU rules.

That is because of the existence of a veto mechanism at Stormont known as the Petition of Concern.

The Irish government agreed on an interim Brexit deal with the UK in 2017

Will the Irish government go for this?

It seems unlikely at this stage.

From the Irish government's point of view, they made an agreement with the UK in the 2017 Joint Report - a kind of interim deal - which said there would not be "any physical infrastructure or related checks and controls" as a result of Brexit.

That was not just an agreement to prevent any new infrastructure at the Irish border, it was any new checks on the island of Ireland.

So the Irish government's position has been that the UK agreed that the status quo would be maintained for cross-border trade.

What Boris Johnson is proposing on customs would not meet those criteria.

- Published2 October 2019

- Published2 October 2019