Margaret Thatcher: 'A shrill and ageing woman'

- Published

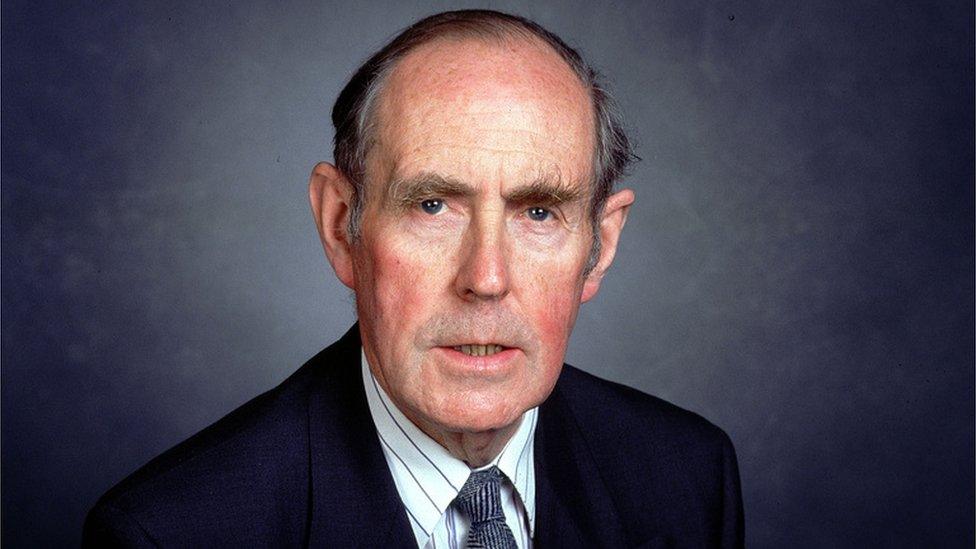

Charles Haughey and Margaret Thatcher were two powerful personalities who didn't always see eye to eye

Newly-released Irish state papers from 1989 reveal previously hidden aspects of Anglo-Irish relations from this turbulent period.

In one telling comment the Irish ambassador to London reports that Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was now seen as "a shrill and ageing woman".

The documents suggest that by 1989 relations between Mrs Thatcher and Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Charles Haughey were less cantankerous than they had been.

Paramilitary violence continued to dominate the headlines in Northern Ireland.

It was the year that saw the UDA murder of Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane and the IRA murders of senior RUC officers Harry Breen and Bob Buchanan shortly after they left a meeting in Dundalk Garda (Irish police) station.

However, the violence did not dominate talks between the two prime ministers to the extent that it had in the previous years.

Gerry Conlon, one of the Guildford Four, was released in October 1989

At the December European Council meeting in Strasbourg, Mr Haughey pressed Mrs Thatcher to re-open the case of the Birmingham Six.

It emerged years later that the men had been wrongly convicted of the 1974 IRA bombing of pubs in Birmingham at the cost of 21 lives.

Mr Haughey's pressure followed the release of the Guildford Four - three men and a woman who were wrongly convicted of another IRA pub bombing in 1974, which resulted in the loss of five lives.

The releases led to the disbandment of the West Midlands Serious Crime Squad, which was accused of incompetence and abuse of power.

Mrs Thatcher maintained that the Birmingham Six case had already been before the Court of Appeal and she could not interfere with the courts.

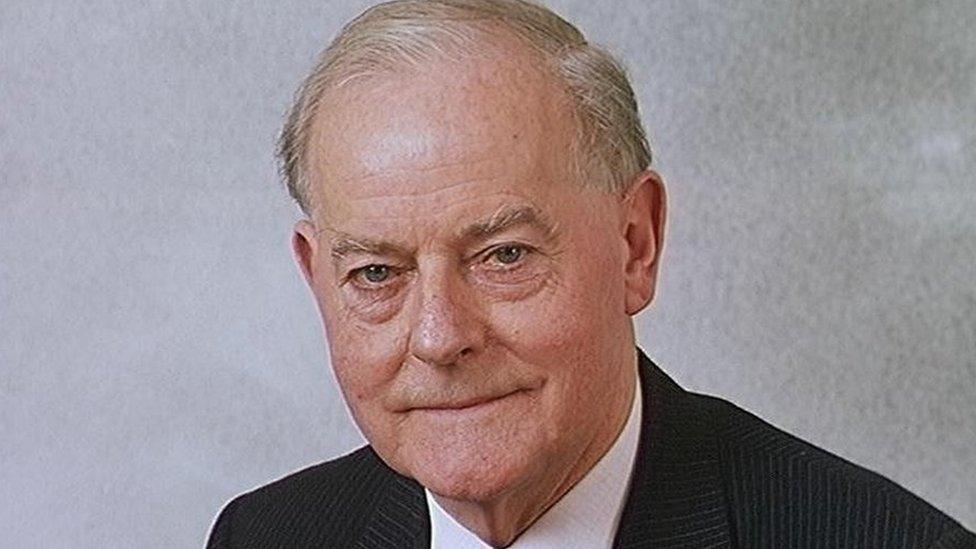

Northern Ireland Secretary Peter Brooke was highly regarded by both prime ministers

Both leaders spoke highly of the new secretary of state, Peter Brooke, who had said that if the violence ended, political talks involving paramilitary-linked parties could follow.

He had also said it it was difficult to envisage an IRA military defeat and that the UK government "would need to be imaginative" if terrorism stopped.

At a meeting in Madrid in June, Mrs Thatcher had complained about "an awful lot of Semtex (plastic explosive)" which appeared to be around.

She also raised the Fr Patrick Ryan extradition case, but not in a hostile way.

Speaking to the BBC in 2019, Patrick Ryan said Margaret Thatcher was right to say he had an "expert knowledge" of bombing

The Irish government was refusing to extradite Fr Ryan, who was wanted in the UK to face IRA-related bombing charges, on the grounds that he could not get a fair trial because of media and political comments about his case

By mid-1989, senior British politicians had settled on "disappointing" as their preferred description for the failure to extradite.

Duisburg was the venue for secret talks between some of Northern Ireland's party leaders

1989 also saw prominent politicians in the DUP, SDLP, Alliance and the Ulster Unionists take part in secret talks at Duisburg in Germany aimed at breaking the political deadlock.

The Irish government papers suggest that most of those involved blamed the Alliance Party for leaking details of the meetings to the BBC.

Another reported to Dublin after meeting John Hume that the SDLP leader was "critical for the first time of Joe Hendron, the party's West Belfast representative and is giving thought to replacing him with Brian Feeney".

But Mr Hume stood by Dr Hendron, who was elected an MP three years later.

Jim Molyneaux: One Conservative MP described the UUP leader as 'a decent man, but no leader'

Not for the first time, Ian Gow, a Conservative MP who had resigned as a minister in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Agreement, was privately critical of the Ulster Unionist leader Jim Molyneaux.

Mr Gow, who would later be murdered by the IRA, told an Irish official, Joe Hayes, in November 1989 that "Molyneaux is a decent man but no leader".

Conservative Party frustration with unionism and the apparent absence of leadership is a running theme in much of what was reported back to Dublin.

'Unionists are like children'

Lord Gowrie, a former UK minister, told an official that: "The unionists have shown no sense of what is good for them. They are like children. They have to be taken in hand for their own good."

His belief was that this could only be done by Dublin and London.

The Irish officials were also very keen to pick up on what was happening in the Ulster Unionist Party.

Irish official David Donoghue reported back from a lunch he had with Jonathan Caine of Conservative Central Office, who would later serve several Tory secretaries of state for Northern Ireland before being made a lord.

Mr Caine, who had contacts with the UUP, was quoted by the official as saying that Molyneaux was reluctant to hand over leadership of the party to John Taylor, then one of his MPs.

He said: "Caine expects the UUP leader will delay his retirement until an alternative successor is in sight."

Mr Molyneaux's successor, David Trimble, became an MP in a by-election the following year and party leader in 1995.

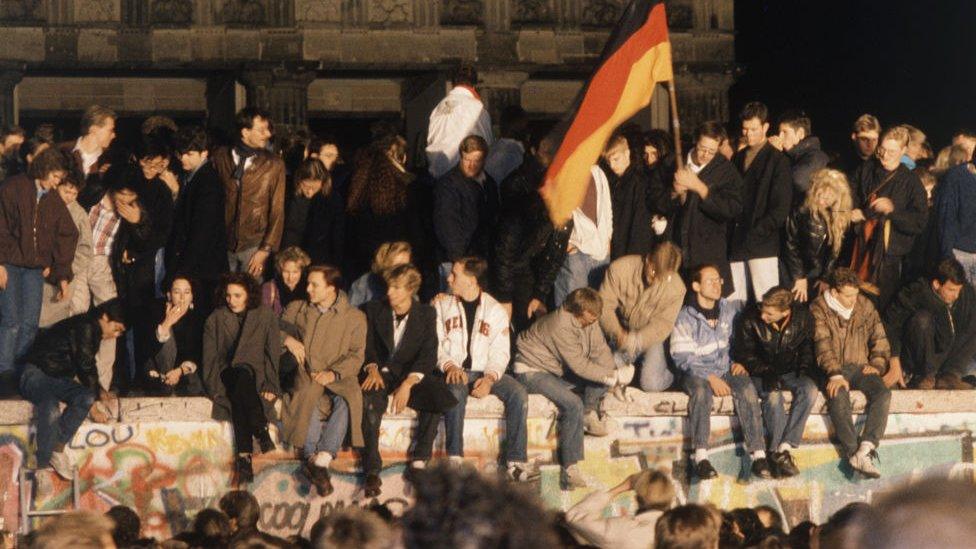

The fall of the Berlin Wall had profound implications for the future of the European Union

What is most striking from the meetings between Mr Haughey and Mrs Thatcher is the amount of discussions they had on European issues.

Ireland was to assume the six-month presidency of what became the the European Union in January 1990.

This was the period of the fall of the Berlin Wall, in November 1989, and the beginning of the end of Mikhail Gorbachev's Soviet Union and the Iron Curtain.

Mrs Thatcher told Mr Haughey: "Gorbachev doesn't want German unity. Neither do I."

But within a year Germany was united and Mrs Thatcher was no longer prime minister.

She also complained about the European Social Charter that was intended to improve workers' rights, saying: "People didn't know what they were letting themselves in for."

As for talk of European monetary union, most of those leaders who did the talking "hadn't read the papers".

She warned that: "A community where three (countries) contributed and nine were net beneficiaries couldn't survive."

Margaret Thatcher left Downing Street in November 1990

The Irish government papers also reveal a sense that the Thatcher era may have entered its twilight phase.

The Irish ambassador to the UK, Andrew O'Rourke, reported back to Dublin in November that "after 10 years of strong leadership there is now an image of a shrill and ageing woman, lacking judgement and unable to get on with her colleagues in government".

Another official, Richard Ryan, reported after a meeting with Lord Gowrie, a former British minister, that she was "moving into the legacy phase of her life and he gets the whiff of political mortality from her".

Within a year, she would be forced to resign mainly because of her attitude to European integration.

- Published30 December 2018