Anorexia: 'My mum was waiting for me to have a heart attack'

- Published

Debbie is now a trained psychotherapist

When Debbie Howard was told that her eating disorder could cause her teeth to fall out, she dreamed about how much weight that would mean she could lose.

Doctors warned her that she was on the verge of cardiac arrest but she thought they were just trying to scare her.

The life of the Commonwealth Games gymnast, from Bangor, County Down, had spiralled out of control.

But there was no suitable treatment in Northern Ireland to save her. Now she is fighting for change.

"If I could tell my teenage self anything, it would be to ask for help," the 37-year-old told BBC News NI.

That's because it took Debbie more than a decade to ask for help with her anorexia.

And as her parents, Paul and Pam McLarnon, and her younger brother, Ricky, learned, an eating disorder can affect the whole family.

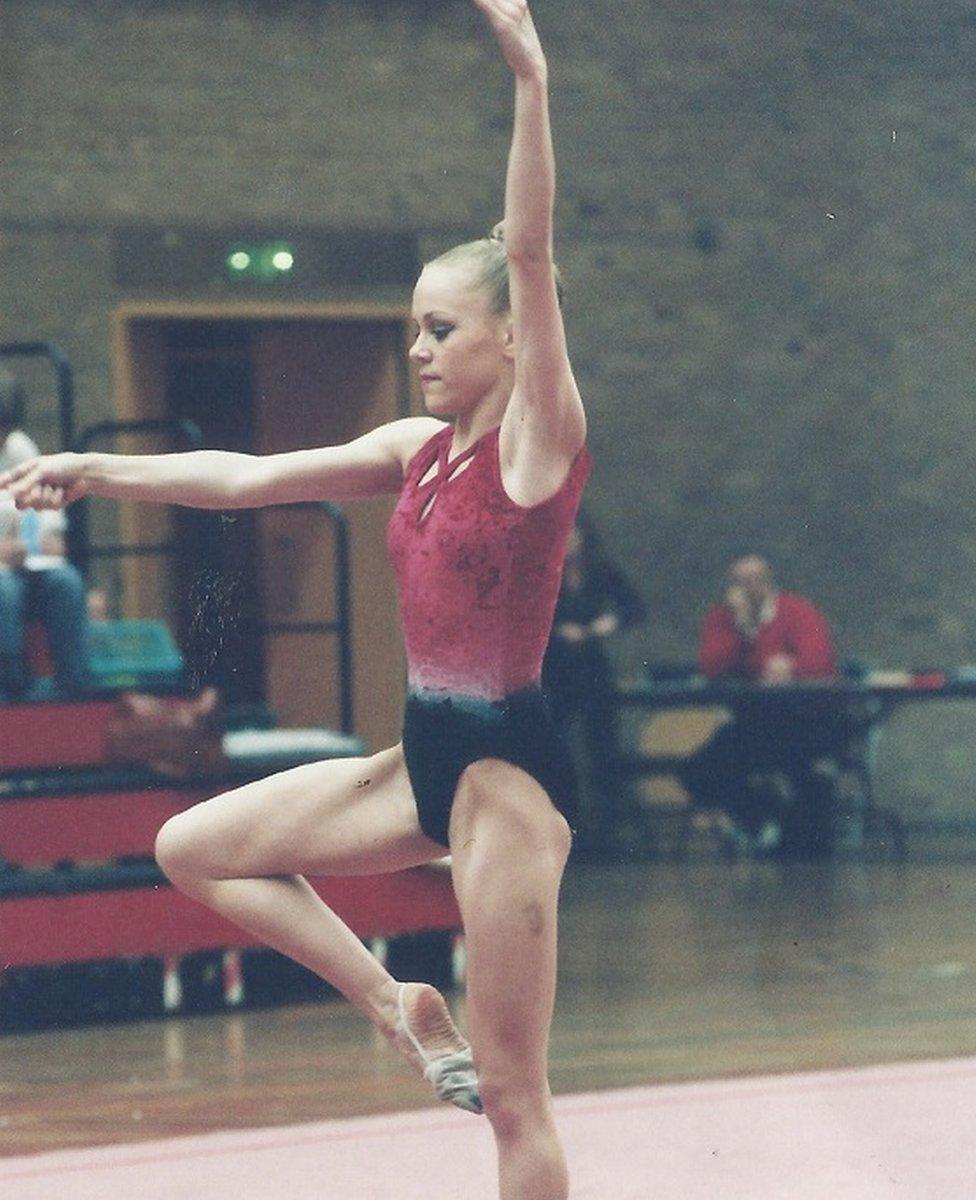

Debbie, pictured as a teenager, during her days as a gymnast

But 15 years ago, when Debbie was at her worst, her family, like many others, did not know how to deal with it.

The McLarnon family set up FightED to provide support and advice for families who have a loved one with an eating disorder.

Debbie was just 12 when she developed an eating disorder.

What is an eating disorder?

According to the NHS, external, an eating disorder is when you have an unhealthy attitude to food, which can take over your life and make you ill.

It can involve eating too much or too little, or becoming obsessed with your weight and body shape.

An eating disorder can be developed by men and women at any age, but most commonly affects teenage girls.

"As a gymnast, there was a lot of pressure to be skinny and we were weighed every day," she said.

"It started out with cutting out cakes and biscuits and ended in me eating next to nothing and nearly dying."

When she was 16, Debbie was training six hours a day on a stomach of two slices of dry toast and some Pepsi Max.

She then went home and did her best to eat as little as she could at the family dinner table, before punishing herself with sit-ups in her bedroom.

"I still felt fat," admits Debbie.

A year later, Debbie gave up gymnastics.

"It meant I gained weight and I couldn't cope with it. I felt obese," she said.

"Everything I ate, I had to throw up. My eating disorder had gone on for so long that I didn't know what normal eating was."

'I was just so tired'

Debbie's parents found laxatives in her school bag and took her for help.

She was warned of the risks of an eating disorder: infertility and hair and tooth loss, but it didn't matter to her.

Five years later, and now living in London, Debbie "just got to a stage where I was so tired".

"It had been 10 years of restricting my whole life and I was exhausted. I remember thinking about how I couldn't live for another 60 years like this."

She told her mum she needed help and began seeing an eating disorder specialist in London.

"It was everything that Northern Ireland didn't have, and still lacks," she said.

But after two years, she was told she had to go back to Northern Ireland due to concerns over her safety.

"The psychiatrist told my mum that my heart was the last thing working in my body and I had to go home so there could be a care plan in place," said Debbie.

"I remember sitting in the chair, thinking that everyone was making a big deal, trying to scare me out of what I was doing."

Debbie Howard is now a trained psychotherapist

When she came back to Northern Ireland, her family campaigned for better services.

"There was nowhere for me to go like there was in London," said Debbie.

"My mum was just waiting around for me to have a heart attack and then she would drive me to A&E."

Debbie was so ill that it resulted in the government paying for her to fly to London every Wednesday for her appointments.

"It was a lifeline for me and I never missed a single appointment."

The Health and Social Care Board told BBC News NI that it currently refers about 1% of patients (fewer than 10) outside of Northern Ireland for treatment, at a cost of £620,000 per year.

Better services

It said funding for such treatment is only available to people whose "specific needs are complex and outside of the normal needs for people with the specific condition, and the treatment they need is not available in Northern Ireland".

It also said that an average of £1m is spent locally treating adults with an eating disorder in inpatient facilities in Northern Ireland.

"Work is ongoing to consider the options for improving eating disorder provision across the region," it added.

Her family's dream is to set up a facility for people with eating disorders, to reduce the need to go to London for treatment.

"If you go to therapy, you're usually there for 50 minutes, once a week. How are families supposed to know what to do for all the other hours in the week?

"We want a homely place for people to go, rather than something clinical. We want people to feel safe.

"Eating disorders are like coping strategies. You've got a whole bunch of things that you don't want to feel and you think you're able to keep a lid on all of those things by allowing your eating disorder take over.

"But things can get better."

If you’ve been affected by eating disorders, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.