State papers: Officials' concern at internet 'propaganda war'

- Published

The broadcast ban on Sinn Féin operated from 1988, but broadcasters in Northern Ireland got around it by dubbing Sinn Féin speeches and interviews with an actor's voice, repeating the interview word for word

The issue of whether to continue the UK government's broadcast ban on Sinn Féin in the run-up to the 1994 IRA ceasefire concentrated minds from Downing Street to the Northern Ireland Office (NIO), according to previously confidential files just released.

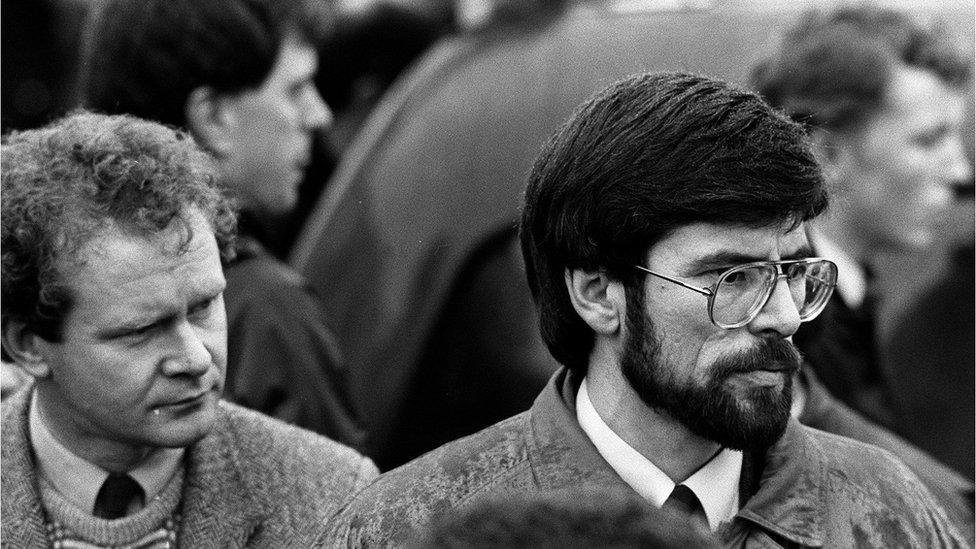

The issue came to the forefront in November 1993 when a Conservative MP alleged at Prime Minister's Questions in the House of Commons that in a recent interview on the Shankill bombing, then Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams "had stretched the broadcasting restrictions to the limit".

As a result, the then Prime Minister John Major asked Peter Brooke, the national heritage secretary, to examine the operation of the broadcasting restrictions in relation to Northern Ireland.

They had been introduced by the Home Office in 1988 to exclude violent groups from the airwaves.

The view then was that such appearances enhanced the standing of such organisations.

'Martyrdom syndrome'

In a memo, dated 9 November 1993, Peter Edwards of the Department of National Heritage (DEN) informed David Cooke from the NIO: "This is in response to concerns about the way that broadcasts have been using sophisticated lip-synching techniques to give a very realistic impression of the Gerry Adams' voice during interviews with him."

In a response, DJ Watkins of the NIO was critical of the ban on Sinn Féin spokesmen.

Many nationalists, he argued, "consider the ban… only contributes to the martyrdom syndrome on which Sinn Féin and the PIRA (Provisional IRA) survive, not to say thrive, and prevent any real opportunity for Sinn Féin to be questioned particularly about issues which might embarrass them… I strongly share that view".

Mr Watkins argued that if the government's aim was to remove a grievance from republicans, they should consider ending the ban.

The official concluded that while the NIO would not be in favour of lifting the restrictions at that time, such a move might be seen as "an imaginative" way in which the government might respond to the ending of IRA violence.

In a memo to John Major, dated 11 February 1994, the Home Secretary Douglas Hurd recalled that during Gerry Adams' visit to New York, he had enjoyed widespread sympathy on the issue.

He recommended lifting the ban in advance of the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis (annual conference) in February.

'Pro-active PR vehicle'

It was not lifted until September 1994.

The papers also highlight Whitehall's alarm at the republican movement's increasingly successful use of the internet for propaganda purposes and their own belated attempts to combat this.

The possible threat to British national security from a sophisticated Sinn Féin website was raised by the junior Home Office Minister, David Maclean, in a letter to Sir John Wheeler on 12 March 1996.

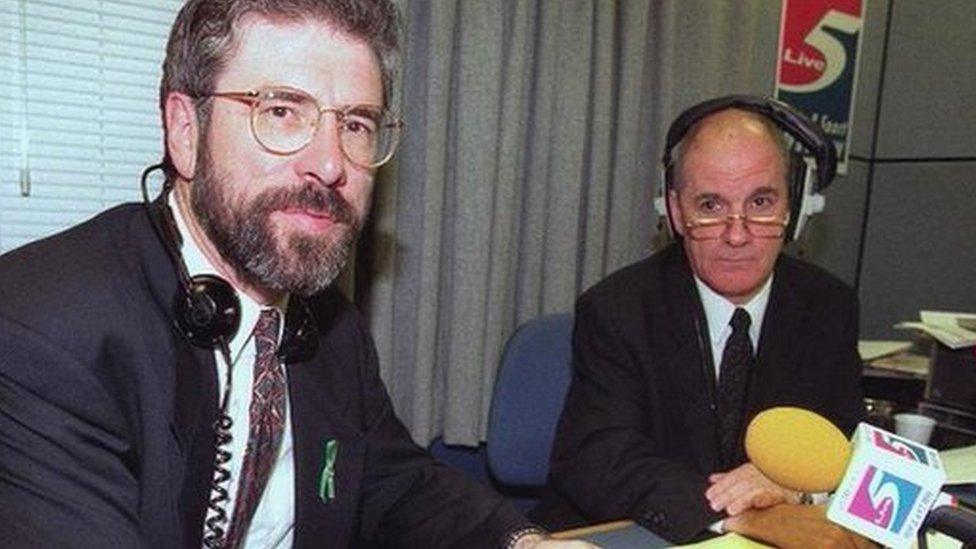

The then Sinn Féin President, Gerry Adams, speaking on BBC Radio Five Live to promote a book in September 1996

Mr Maclean wrote, enclosing documents from a Sinn Féin website: "Amongst the unsavoury nasties were these very professionally produced pages, apparently showing our complete (military) deployment in NI".

The material gave details of British military, Royal Navy, RAF and Royal Irish Regiment numbers in Northern Ireland with a detailed list of permanent vehicle checkpoints (PVCs) in border areas.

Mr Maclean wondered whether, since the internet already had nine million American and one million British users, the British Government should be putting "our own counter-propaganda on the net".

Mr Wheeler replied, expressing his "horror" and asked his officials to explore the matter.

'Pro-active PR vehicle'

The issue was discussed at the NIO Security Information Group at Stormont Castle on 3 April 1996.

The meeting noted that Sinn Féin was using the internet to good advantage.

Officials also learned that the NIO had a website but that it was essential for the government to use the internet as "a pro-active PR vehicle".

It was agreed that the Royal Ulster Constabulary and military would provide appropriate material.

- Published22 January 2014