Lost Lives: An egalitarian 'monument to the dead'

- Published

The film, Lost Lives, is a requiem for those killed in the Troubles

Not long after Lost Lives was published in 1999, it was reported to be the most stolen book in Belfast.

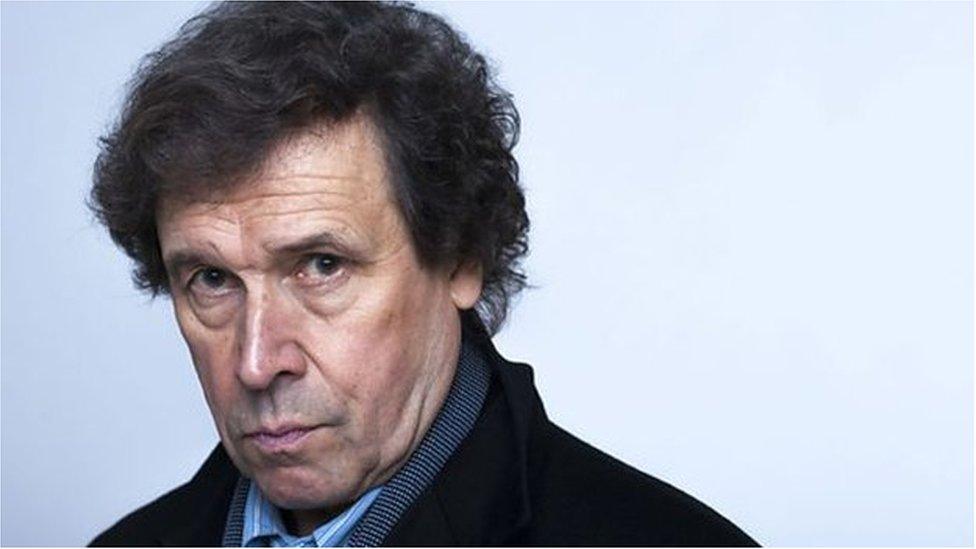

This factoid always delighted Seamus Kelters, the second-named author of the book and originator of the project, not least because he thought it was a tribute to the ingenuity of the city's shoplifters.

At more than 1,600 pages, a thickness greater than some editions of the Bible, and weighing something like an average roast, theft of the object involved substantially more than sliding it into your waistband and strolling out the door.

But Seamus mostly understood that this was a sign of the book's egalitarian appeal; that Lost Lives' goal, which was simply to record every death caused by the Troubles, was recognised and appreciated as much by thieves as it was by professors.

Monument to the dead

With hindsight, that was also an early sign that Lost Lives represented something more than the sum of its parts.

In the years after publication, the book was regarded as a monument to the dead and an act of historical recovery simply because it recorded all the deaths without judgement.

Its power, it's been often said, lay in its sober, straightforward presentation of terrible facts.

For many years a church in Dublin read from it continuously over the Easter weekend. Some people kept it in their homes as, apart from a grave, the only memorial to a loved one.

Now it has become a remarkable film, a visual poem that will be shown on Sunday on BBC One Northern Ireland; one that takes small portions of the book, and with the powerful additions of pictures and music, turns the words into a larger expression of Northern Ireland's grief.

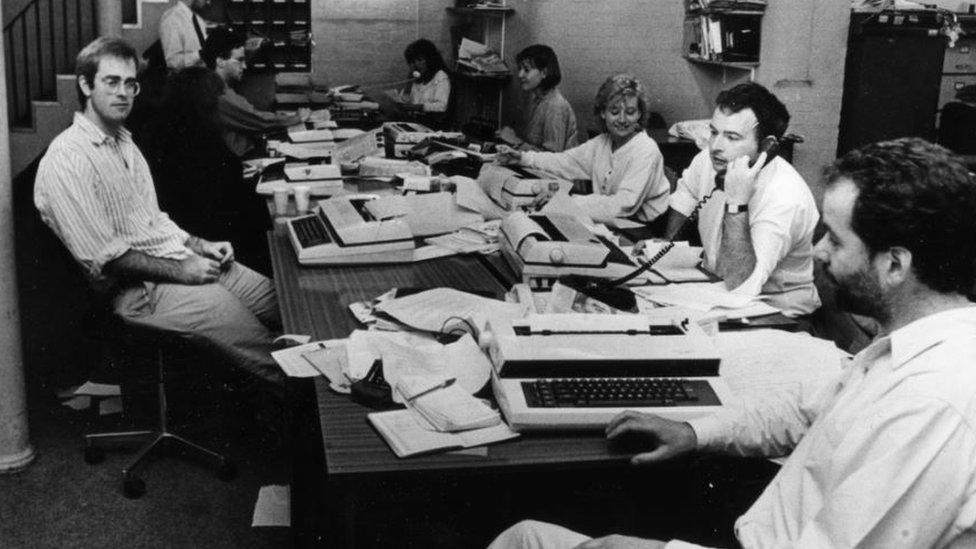

Chris Thornton, left, and Seamus Kelters, on the phone, in the Irish News

It was never intended to be those things. Lost Lives started partly as a reference work, originating in the Belfast Irish News.

Seamus Kelters, then the paper's main news reporter, had been assigned to write a project on violence in north Belfast, where something like a fifth of all killings had happened.

I was asked to help him.

The most demanding part of that project was a list of every killing in north Belfast, which at that time amounted to more than 600 names.

It was an extraordinary exercise. Records were scant and in the worst days of the Troubles, newspapers hadn't been able to keep up with the death toll - some killings were mentioned briefly, then forgotten in the next wave of violence.

We spent weeks poring over books and old newspapers, and tapping the information into a computer: names and ages and personal details of people, some of whom were the parents or brothers or sisters of our colleagues and friends working beside us.

It was an early indication of the sensitivity of the project.

'Should we keep going?'

We finished the north Belfast list, my memory says, one lunchtime when we were the only people in the newsroom.

Since we had recorded so many deaths, Seamus asked, "should we not just keep going?"

To do that we approached David McKittrick, then the London Independent's Ireland correspondent, a man already recognised as one of the foremost chroniclers of the Troubles and someone who had a considerable personal archive.

Then we recruited Brian Feeney, who carried the benefits of academic rigour and intimate knowledge of north Belfast.

David McVea, another academic and student of the Troubles, joined not long after. Dozens of others contributed their knowledge, advice and practical help.

Over the next seven years, the list of killings gradually grew into accounts of every death in the Troubles from 1966, about 3,600 people by the late 1990s.

A still from the film which combines beautiful imagery with the horrors of footage from the Troubles

It became apparent (to us at least) that the database of victims was the basis for a reference work, but publishers were harder to convince.

At a million words, it was said to be too big and unwieldy, and would be of interest to only a small number of people.

It was Mainstream in Edinburgh which agreed to publish, with the support of the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust and the Ireland Fund.

Lost Lives first appeared not long after the Good Friday Agreement, and that timing is probably important in understanding the book's impact: it came at a moment when Northern Ireland was just beginning to look at the immensity of what happened over the previous 30 years.

The book was never meant to be an elegy, but in the absence of anything else it was treated like one.

Two decades later, with the book long out of print, the superb filmmakers Michael Hewitt and Dermot Lavery became dedicated to the idea of turning Lost Lives into a television programme.

It was a puzzling suggestion: their production company, Doubleband Films, has an immense creative reputation, but how could a book with no narrative be turned into a film? The idea seemed like making a movie out of the dictionary.

It turns out they knew what they were doing. It's often been said that any random page of Lost Lives encapsulates the immense grief and suffering of the Troubles, and the film of Lost Lives captures that idea.

A small selection of the book's entries, read by Ireland's' best actors, including Jimmy Nesbitt (above), conveys the bigger picture of what happened to Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

The power of those terrible facts is enhanced by seeing the faces of those who died and the loved ones they left behind.

It is an intense experience - when it was shown in cinemas at the end of last year, audiences invariably left in sobered silence - but it is also compelling and important.

A lasting legacy

In what are nearly the very first words of Lost Lives, David McKittrick admitted that the authors "shed tears while researching and writing it".

We have again.

The supreme irony is that the man who McKittrick described in that introduction as the heart of the project, lost his own life before the film was finished.

Seamus Kelters contracted cancer in the early stages of the production and died in September 2017 at the age of 54.

He would be the first to point out that his death had nothing to do with the Troubles, and so lay outside the criteria for inclusion in Lost Lives.

Nevertheless, his lost life also deserves to be recorded: a journalist, author and married father-of-two, he was the originator of a monumental book, and the inspiration for a remarkable film.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised by this story you can contact the BBC Action Line.

Lost Lives will be available on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published10 October 2019

- Published26 February 2017