Invisible wounds of trauma that cut deep

- Published

GPs said 3,500 people attended with overwhelming anxiety and distress following the Omagh bomb

Hanora will never forget the little boy she saw lying on the street after the bomb exploded.

Stuart wakes up from nightmares of babies screaming - the babies he could not save.

Hanora and Stuart witnessed at first hand the Omagh bombing in August 1998. Their wounds may not be visible, but the bomb left ugly scars.

A new documentary from BBC Northern Ireland reveals the impact of severe trauma on four individuals.

All suffered post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

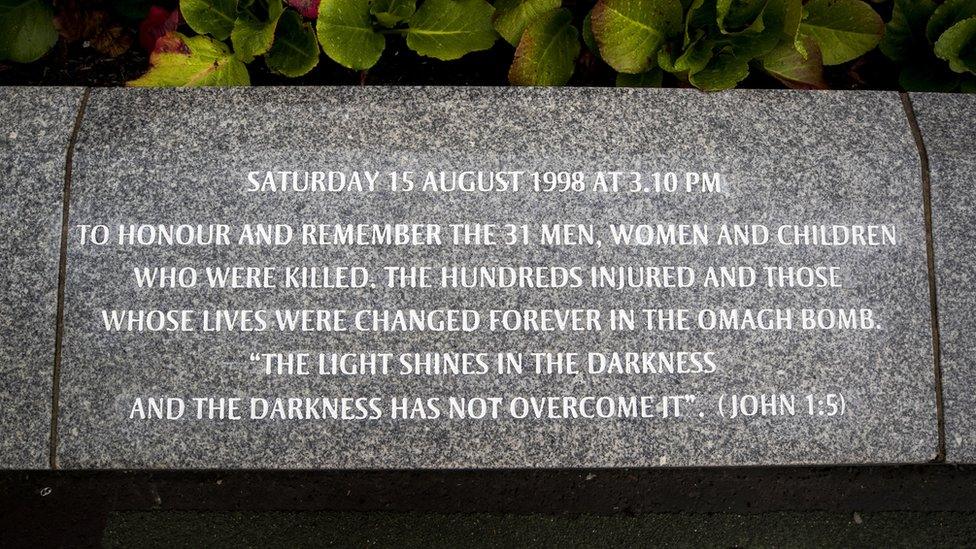

For Hanora Raflewski and Stuart, it started on 15 August 1998 when the Omagh bomb exploded, killing 29 people, including unborn twins, and injuring more than 300 others.

On the 20th anniversary of the Omagh bomb, a little girl lays flowers in memory of those who died

Hanora was 15 years old and was in town with her friends. They were standing in a circle about a car and a half's distance away from the bomb.

She remembers seeing a ball of fire, being lifted into the air and waking up to find a friend, nearby, covered in blood.

She remembers her feet were bare - her shoes blown off - and she remembers running.

After the bomb, she changed. She was angry, irritated. Time passed.

The 9/11 bombings triggered Hanora Raflewski's flashbacks

On her first day at Queen's University in Belfast, the 9/11 attacks happened in the United States and it triggered her trauma. She felt that the world was going to end.

She stayed in bed, did not eat and lost a lot of weight.

She was plagued with flashbacks. She remembered that little boy lying on the street in Omagh and felt paralysed and thought how she should have reached out.

She remembered picking up an umbrella and hoping the blood on it was not from someone she knew.

For Stuart, a policeman, who ran out into the aftermath of the bomb, it was the pregnant woman in the rubble whom he couldn't save that haunts him.

"I should have dug her out, I could have done more," he said.

After the Omagh bomb, he changed, too. He felt so angry. His work and his family life were in turmoil.

He said he was suicidal and drove himself to a psychiatric ward.

"You need to be referred by your doctor," they said.

"Take me now or you'll never see me again," he told them.

Mark witnessed the Westminster attacks

For Mark McCormick, in 2017, life was sweet. He had moved to London, he was in a steady relationship and he had found a career doing something he loved.

It meant a trip to Westminster on 22 March.

He was standing looking down from a window onto Westminster Bridge when a man driving an SUV ploughed into pedestrians.

He saw the attack in which six people died, including the attacker, as it happened.

It started to haunt him. He stopped sleeping, he lived in constant anxiety; became frightened in public places; suffered a panic attack.

Flowers left to remember those who died in the Westminster attacks

For Claire, who wanted to keep her identity private, it was rape - and more than once. Even the feel of a particular cotton duvet could trigger her flashbacks.

These were so intense and so terrifying that she would have done anything to avoid them.

"I'd be sorry that lobotomies don't exist any more," she said.

In 2011, Northern Ireland had one of the highest rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in the world.

But while this documentary charts the effect of severe trauma on people's lives and the psychological pain that is PTSD, it also offers real hope.

Dr Michael Duffy and his team have been treating extreme trauma for more than 30 years. He is one of the world's leading experts.

He began his career in the Mater Hospital in north Belfast in the 1980s and 1990s where he met huge numbers of people who had been exposed to shootings and bombings.

Some became hyper-vigilant and cut themselves off from the world - all the time on the lookout for danger and reliving their trauma. This was PTSD.

The Troubles may be over, but many people remain hyper-vigilant, scared to go into certain areas, isolating themselves from the world. Their troubles are never really over.

Dr Duffy was instrumental in setting up a trauma centre in the aftermath of the Omagh bomb.

At that time, GPs had reported 3,500 people coming in with overwhelming anxiety and distress.

He also advised others in the aftermath of 9/11, the Manchester Arena and the Norway attacks.

Dr Michael Duffy says people with PTSD can recover with the proper help

His message is positive.

"People with PTSD can recover very well if they get adequate, evidence-based treatments," he said.

"Sadly, the reverse is also true. If people don't get access to these treatments, they can suffer for many years."

This documentary follows people using Cognitive Behaviour Therapy to help their recovery.

Mark braced himself to return to the scene of the Westminster attacks.

Hanora visited the little boy's grave.

She understood that he was no longer lying on that street, that his family had cared for him and laid him to rest close to them. She understood that there was nothing she could have done.

"To say I was mentally injured by it (the bomb) seems trivial at times," she said.

"On an emotional level, it feels like I got away easily, because I did walk away. I'm eternally grateful that I walked away.

"But I walked away injured - just in a very different way."

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story you can contact the BBC Action Line.

PTSD - Stress of the Past is on BBC One Northern Ireland at 21:00 on Monday 17 February.

- Published22 February 2019

- Published28 January

- Published1 October 2019

- Published22 November 2018