Trail gone cold: The heartache behind NI's missing people

- Published

Danny Cullen and Joanne Conway have both experienced what it's like to have a loved one go missing

What would you do if a loved one simply didn't come home? Vanished.

It's an anguish felt by thousands of families across Northern Ireland every year.

Some live with heartache after a relative's body is found, others shoulder the unbearable burden of not knowing what happened.

Police received more than 60,000 reports of people missing in Northern Ireland between 2013 and 2018

A family's pain

"When somebody dies you have to accept it. When somebody is missing you can't accept it."

For Joanne Conway, the trail has simply gone cold.

Her face lights up when she talks about her brother, Gerard, the eldest of the family, now missing from his home in Cookstown, County Tyrone, for 13 years.

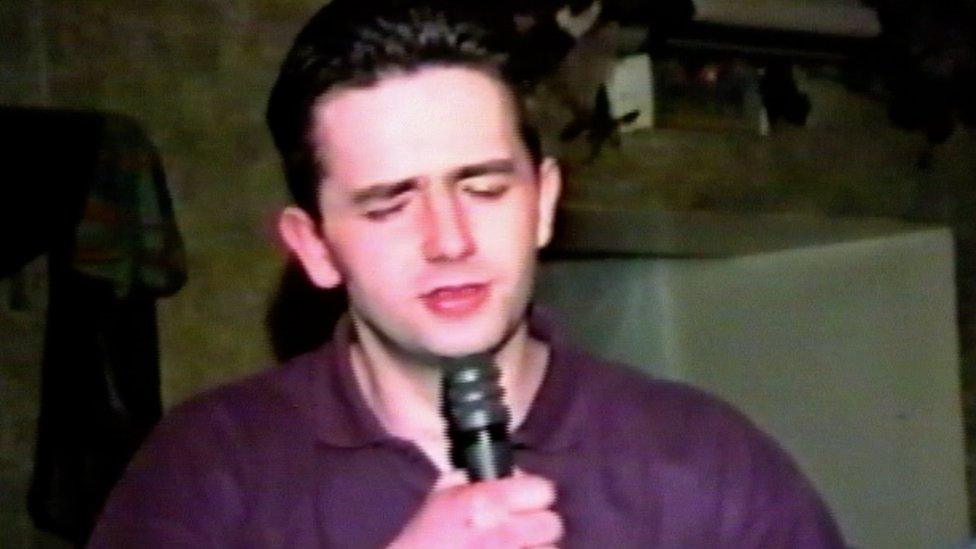

Home footage of Gerard Conway singing in April 1993

A kind, generous man, she says, who was funny, and loved English, history, politics.

"We'd lots of good times, we definitely liked going out together, going to the pub. He loved singing, we all loved singing and dancing. He always made you feel safe.

"He would tell you how it is - if it was good, bad or ugly, he'd tell you. He was honest. He was a good big brother."

Gerard Conway is still missing, 13 years after he left his home in County Tyrone

But there is a deep sadness, coupled with a frustration that so many years have passed, and Gerard, then 32, is still gone. Gone, seemingly without a trace.

Gerard had bipolar disorder. The last recorded sighting of him was at a bank in Cookstown on 25 January 2007.

At the time, his mother offered a reward of £100,000 in an attempt to find him, external.

Joanne says: "We tried to contact anyone we knew he would have hung about with. Everything was, sort of, coming up quiet.

"We got posters made up all, went all around Cookstown and surrounding towns. Nothing, nothing. It was scary, you feel like, this isn't happening.

"But it was happening. You are clutching onto straws, trying to find ways, solutions, answers, but everything was coming back blank."

Joanne Conway says if she knew where her brother, Gerard, was, she would bring him home

In the five years up to December 2018, the PSNI received more than 60,000 reports of missing persons in Northern Ireland. The vast majority turn up - 80% are usually found within the first 24 hours - but 119 have been recorded as dead.

Fifty-eight are still considered as long-term missing persons cases and the police say they are kept actively under review.

For the Conway family, the hours of waiting for Gerard to come home turned into days; the days turned into months and the months into years.

Police renewed their appeal for information in 2017 - the tenth anniversary of his disappearance.

But the PSNI said at that time that despite "extensive" enquiries over a number of years, including liaison with police in the Republic of Ireland, there were "no clues as to his whereabouts".

The most recent police search for Gerard Conway took place around the Drummond Wood area of Cookstown in June 2020, but nothing was found.

Joanne says the passage of time has not made her brother's disappearance any easier to bear.

"It's had a huge impact on our family. It's created so much tension and stress, anger. You need to find him in order to move on, fill the gap, fill the missing link."

The family accept that Gerard is dead, but there are many unanswered questions.

2013 - 2018More than 60,000 reports of missing people

Deceased119 recorded as dead

Found80% usually found within the first 24 hours

Still missing58 are considered long-term cases

"What happened to him, where is he? You need answers. You find them, you can have your funeral, you can bury them, feel like you can go and talk to them," she says.

"You lose a lot of anger, a lot of frustration that's staying with somebody just disappearing without trace, you just can't accept it.

"I often think if it was me missing, Gerard would have me found, he'd have left no stone unturned. For me I feel: 'What can I do to find him?'"

The family have their own theories about what may have happened to Gerard - most of them believe he was murdered after "getting mixed up with the wrong people".

However, Joanne says: "I don't know what happened to Gerard. If I knew, we'd have him.

"The other scenario would be if Gerard had maybe committed suicide and there was no foul play involved. But we can't accept that. I can't accept that."

'We woke up to a nightmare'

For several weeks, the face of 33-year-old Michael Cullen stared out of "missing" posters on lamp posts and flyers around his home city of Belfast.

A researcher at Ulster University, Michael was also an award-winning beatbox performer who was passionate about fitness. He was last in contact with his family on 9 January 2018.

Michael Cullen went missing in January 2018

His brother, Danny, remembers his family's shock when they discovered Michael was missing.

"I was at the house and we found out that Michael wasn't responding to us at all," says Danny. "At that stage it was completely out of character for him and that's what alarmed our family.

"During that time it was very difficult. It seemed like every day was the same. There was a lack of sleep and when you'd wake up, it'd be like waking up to your nightmare.

"Around that time was devastating and I wouldn't wish it on anyone."

Michael Cullen was an award-winning beatboxer

Michael Cullen's family experienced the unimaginable distress of not knowing where he was for 22 days.

There was a massive search, involving police, community groups and, at one point, a police drone.

His family played out every scenario in their head. Was Michael injured? Was he just trying to get some space?

For several weeks, the face of 33-year-old Michael Cullen stared out of "missing" posters

"Every single day we were out there from light until dark and it [the search] involved community search and rescue," recalls his brother.

"They were out searching every night with a team of volunteers.

"We had people from everywhere volunteering and the police looking into it. They were all great and heroes for helping us out."

So when the news came that Michael had been found dead, it left them reeling.

"Through the whole search, I didn't think that Michael had taken his own life," says Danny.

Danny Cullen talks of the horror of finding out that his brother, Michael, had disappeared

"I believed that there was a possibility that he would be found alive and, maybe, injured.

"I hadn't believed that he had done anything to himself because I hadn't seen any signs. This goes to show you that there are so many people, they can be walking past you any other day, and you don't see the problems that they face inside."

Link to mental health?

Northern Ireland has the highest rate of suicide in the UK; it is also higher than that of the Republic of Ireland.

In January, Northern Ireland's Health Minister Robin Swann said tackling suicide was a key priority for his department.

Finding out a missing loved one has killed themselves can worsen relatives' guilt, says Siobhan O'Neill, a professor of Mental Health Sciences at Ulster University.

Siobhan O'Neill is a professor of Mental Health Sciences at Ulster University

"Often families feel, somehow, that they might have been to blame, that they didn't spot the signs," she says. "It's frequently very, very difficult to spot the signs.

"Families are tormented with the idea that they somehow could have prevented this. So there's the search for that person and also devastation caused by a suicide."

More needs to be done to tackle what she calls a "very pertinent problem" in Northern Ireland.

Although good services exist for those in a crisis situation, Prof O'Neill stresses: "Seventy percent of those who die by suicide haven't been in touch with the mental health services, and maybe the only connection they've had to the health services has been through their GP.

"We need to be very clear, we need more spending on mental health services.

"Suicide is a preventable death - there's lots of things we need to be doing.

"One of those things is to provide adequate mental health services for people who could benefit from mental health services."

She stresses that not everyone who has a mental health problem will go missing; equally, a life event can be that trigger for someone to simply disappear.

But that loss of someone, that not knowing where they are, can have a cataclysmic effect on a family, she says.

"When you've lost someone and you're searching, that uncertainty has the impact of a trauma on the person's whole sense of existence."

The front line

The police are on the front line when someone is reported missing.

Det Ch Supt Anthony McNally, of the PSNI's Public Protection Branch says the vast majority of people are found in the first 24 hours. Only 4% are missing for longer than seven days.

"While the statistics are important, it's not about statistics for us," he says.

"It's about finding and keeping people safe so I fully understand... those concerns that loved ones have, and that's exactly what the PSNI are here to do."

Det Ch Supt Anthony McNally works in the Public Protection Branch of the PSNI

The police have a number of resources at their disposal.

After an initial call from a concerned relative, a well-rehearsed operation swings into action that can involve trawling through hours of CCTV or the deployment of a police helicopter.

"We will carry out a risk assessment to identify the level of risk that we believe is presented to that person," says Det Ch Supt McNally.

"That allows us to prioritise what resource we can deploy, but the ethos for them all, irrespective of why they went missing, is that we want to find them safe and well and return them to their loved ones."

Police keep the long-term missing cases under review, he adds: There is no timeframe in terms of when an investigation will be closed.

"We very much realise that there's a family waiting for that loved one to be returned," he says.

The psychic medium

In some cases, families will call on other outside parties, such as private detectives or psychic mediums, to help in the search for someone who has disappeared.

Michelle Rooney-Clancy describes herself as a psychic medium.

She has worked with families of some of Northern Ireland's missing who, she says, are desperate for a glimmer of hope.

Michelle Rooney denies she is giving desperate families false hope

They may have exhausted all other areas, she says, and are seeking any sort of connection that could lead them to their loved one.

"What normally happens is someone will contact me, whether it be a family member or a third party," she says.

"I only require a photo of the person who's missing and if there's a map or any other photos of the area, it's appreciated, but they aren't needed."

Michelle Rooney says she has been successful in locating a number of missing people, including a man who had been missing for four years.

Although her claims may be met with some scepticism, Ms Rooney denies that she is giving desperate families false hope - she offers her services for free in these cases.

"A lot would come open-minded. You do get the sceptics - but I just take it for what it is at that given time.

"As a medium, I can only be given what I'm given but it's not to me to explain whatever is given to you in a reading. It's up to the receiver to understand it.

"In the work that I do as a medium, you're aware that it can't be dramatic. You can't give false hope and you can't give a seed of doubt. That would be cruel to do to any family. The information we [mediums] are giving is normally guidance and direction."

She says that, in some cases, families have been encouraged to pass on information she provided to the police, but that she can't say for certain if it was.

Commenting on the use of external sources such as private detectives and psychic mediums, Det Ch Supt Anthony McNally says "all information is valuable" in missing person cases.

But any information is evaluated in terms of what police already know and "anything that may corroborate it", he adds.

He also says that with any investigation into the whereabouts of a missing person, the police should always take the lead.

Joe Apps, head of the NCA UK Missing Persons Unit, echoes that sentiment on the caution with which police treat information provided by mediums,

"I [have] experience myself in how psychics operate and the information coming in from psychics," says Mr Apps.

"Some would appear very interesting in the first instance, but later turn out not to be useful at all."

The missing children

Not all of those who go missing are adults.

According to the Health and Social Care Board, between 2013 and 2019 there were 351 children reported missing from care in Northern Ireland. And there were 762 occasions when children, who are cared for by the state, ran away.

These statistics relate to children who were missing for more than 24 hours.

'No child should ever feel they have to run away'

These children are the most vulnerable people in society, according to Northern Ireland's Commissioner for Children and Young People.

"If you can imagine what it's like to be a cared-for child. You are taken out of your home because your home isn't safe for you, it's not appropriate, you're not being properly looked after and you're taken into another situation," says Koulla Yiasouma.

"You are already quite vulnerable. You are confused, you are concerned. It's not a surprise that you may want to run away, to go to a place where you think you are more likely to be cared for, or you are likely to be looked after.

"More often than not the place you're running to isn't safe for you. It is a place that poses more risks for you. So am I surprised at the number? No, I'm probably not. Do I wish it was less? I absolutely do."

She says most of the children return safe and well, but that poses another question.

"What we need to know is: How long are they away for? Is there a tailored response so when they come back have they been asked what was it that led them to stay away?

"Why did they leave? What can the Health and Social Care Trust do to make sure it doesn't happen again, to make sure they feel safe?"

Life's challenges

The number of people who go missing in different parts of the UK is broadly the same, per head of population.

If someone is missing for three days, the relevant police force must notify the National Crime Agency.

Joe Apps says the highest number of people who go missing across the UK, accounting for 60% of incidents, are aged between 12 and 17.

Most people who go missing across the UK are in the 12-to-17 age group

Children who are being cared for by the state are three times more likely to disappear than children in family settings, he adds.

"Anything that challenges you in life could be a factor that causes you to go missing, whether you are a child or an adult," he says.

"For adults, it can be drugs or alcohol abuse, relationship breakdown, financial worries, worries about family and bereavement - anything you can think of would be a reason for someone to go missing."

'Sense of perpetual torment'

Young or old, male or female, behind each statistic is a person and a family enduring immense heartache.

For some, like the family of Michael Cullen, the discovery of a body ends a frantic search, but it then unleashes a lifetime of grief and unanswered questions.

"I miss him being around," says Danny. "His humour, his laughs and his smile - and just the whole character that he was."

The families of those still missing are haunted by a lack of closure; they live with a trauma every day.

Prof Siobhan O'Neill describes it as a "sense of perpetual torment".

"We need completeness, we need a story, we need to understand where a person is and that's an innate, human need for the story to begin and end," she says.

"People will have beliefs and cultural expectations about what should happen to a person's remains whenever they die. If they don't have that body, then that ending never happens."

For Joanne Conway's family, the waiting is never over. And Gerard's mother is hardest hit.

"It's horrific," says Joanne. "Every day it's torment for her. This is her son, her first-born child that's been taken away. No answers.

"The feeling of despair doesn't leave her, you can see it in her. It's broken her heart.

"I don't think she'll ever be at peace."

Trail gone cold: The Search for Northern Ireland's Missing is on BBC Radio Ulster on 20 June just after the news at 12:00 BST and afterwards on BBC Sounds.

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story you can contact the BBC Action line.