Mental illness: Coping with a crisis in a pandemic

- Published

Oran Sludden, 21, is using his own experience of depression to help others

Just before the coronavirus arrived, another health issue was particularly prominent in Northern Ireland.

It too was being spoken of as a "crisis" and an "emergency".

Northern Ireland has the highest rate of mental illness of any part of the UK.

Proportionally more people take their own lives here, the suicide rate for men is about twice the level in England.

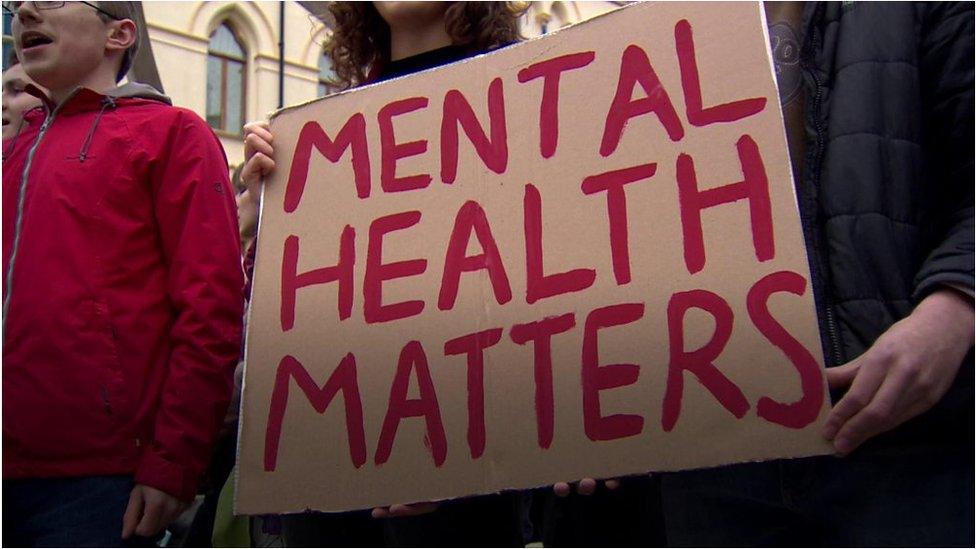

Over the winter, rallies were held, blogs were written, and petitions were signed, calling for urgent action.

Now support groups are warning that the pandemic may be making the issue all the more critical.

The sense of isolation generated by the lockdown can be tough for people with mental health difficulties.

"Not speaking to people can be like throwing everything into a volcano," explains Oran Sludden.

The 21-year-old, from Dromore in County Tyrone, is continuing therapy online during the lockdown.

He was a hugely successful young Gaelic footballer and began to be affected by depression after a severe knee injury removed him from the pitch.

'Over thinking everything'

He is well aware of the impact that a lack of face-to-face contact can have.

"When you're on your own, even the small things that you used to enjoy, annoy you," he says.

"You're just over-thinking everything."

When his illness was at its worst during the last couple of years, Oran attempted suicide.

"I'm thankfully now on the road to recovery, but you just have to take it day by day," he says.

"Not every day's going to be a sunshine day, you have to stick with it and battle through it."

On 1 February, a rally was held at Stormont calling for better mental health services

Oran is now passionate about encouraging people to "open up", seek help, and understand that talking to someone can make a massive difference.

He has set up "Project Hope and Beyond" on Facebook and Instagram - where he shares coping strategies and messages of positivity with hundreds of followers.

"Reaching out is the hardest part for a lot of people.

"During this time, I know it's hard because we're not able to go out.

"But I would encourage people to talk to somebody - on the phone, or on a video call.

"When you look back, you'll see how much better it was not to bottle it up."

'Proper funding needed'

Charities believe there has been an increase in need and they are concerned that people may feel "cut off" from help.

Philip McTaggart founded PIPS - the Public Initiative for the Prevention of Suicide and Self-Harm - after his son, also called Philip, took his own life 17 years ago.

He is worried about a widespread feeling of acute loneliness.

"People are sitting inside - their anxiety levels are high, because they're worried about the virus," he says.

"We know that in Northern Ireland, six people are dying by suicide every week.

"No-one wants that to increase."

He says that mental health services must be factored in to plans to end the lockdown.

"If the resources aren't there, if the proper funding isn't there to deal with it, we're only heading for disaster."

"Let's get things in place so we can save lives."

He is among a number of people involved in support work who argue that although Northern Ireland has a higher prevalence of mental health problems.

Funding for mental health has historically comprised a lower proportion of the health budget than the rest of the UK.

NI's Health Minister Robin Swann said mental health is a top priority

Annie Davey from the 123GP campaign says: "Even before the pandemic we had a crisis with mental health.

"I think now it's certain to get worse."

She thinks a number of lockdown experiences will have psychological consequences - including the restrictions on funerals.

"To lose a loved one and not be able to say goodbye - or as we put it in Northern Ireland, not be able to give them a decent burial - that could play on people's minds for years.

"We need more funding, more resources - and not just for the aftermath of the epidemic."

The health minister in the devolved government, Robin Swann, has acknowledged the "potentially catastrophic impact" of the pandemic on emotional wellbeing.

The Stormont Executive is appointing a "mental health champion" to guide its policies.

When he announced the move last week, Mr Swann said mental health was a "top priority" for him and other ministers.

He added that "if anything, this present pandemic has made this ever more important".

These times of less freedom and more worry have magnified some deep and personal needs, which were already urgent.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

WHAT WE DON'T KNOW How to understand the death toll

TESTING: Can I get tested for coronavirus?

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

- Published17 April 2020

- Published17 April 2020

- Published4 January 2020