Dyslexia: 'Mummy, am I stupid because I struggle to read?'

- Published

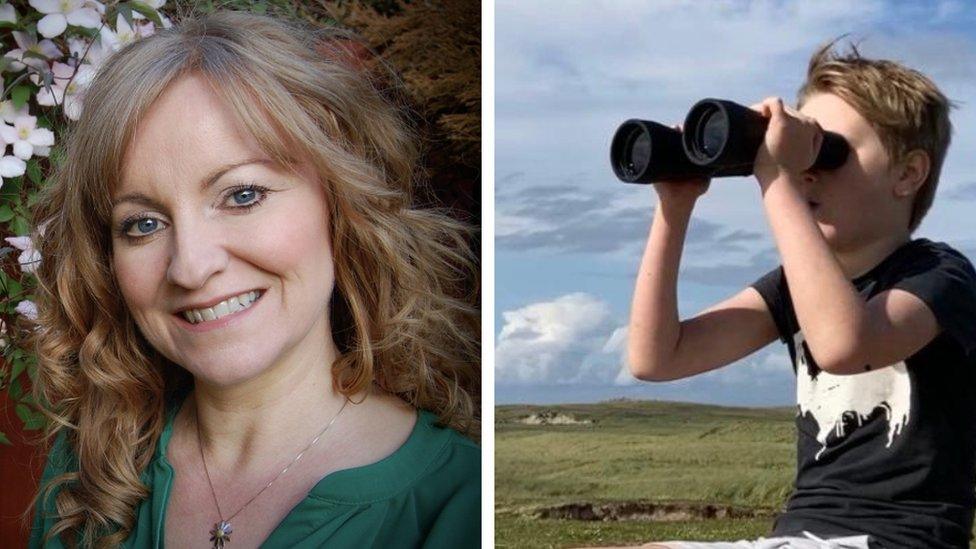

Ciara Riddell's son Shea is among the estimated 15-20% of people with dyslexia

Journalist Ciara Riddell has produced a Radio Ulster documentary describing her efforts to help her son Shea overcome his dyslexia. Here she tells her story.

I closed the storybook and tucked my son into bed with a goodnight kiss. "Mummy," Shea whispered, "am I stupid?"

Shea was in his third year of primary school and it was hard for him because he was having difficulties learning to read.

Later, Shea described sitting in a room full of classmates and looking around in confusion as his friends seemed to easily understand the words on the whiteboard.

He didn't. He was just six years old and felt scared and alone.

The Education Authority doesn't hold official figures for the numbers of children in Northern Ireland schools who have difficulty learning to read, but it's estimated that 20% of children in UK schools reach eight to nine as poor or non-start readers.

According to government figures, it is estimated that 15 to 20% of the population has dyslexia - just like my son.

'Hours of tears'

At school Shea was being taught to read by learning sounds of single letters and then blending them together to sound out a word. So Cuh-Ahh-Tuh becomes cat.

This method is known as synthetic phonics and works for a lot of children - it even worked for my older child - but not Shea.

Shea's school was supportive. He got extra reading lessons, they told us to keep practising at home, that eventually it would 'click'.

It didn't click, however, and his inability to read became an even bigger issue. He was anxious about school because he hated feeling different from his friends, and homework took hours with lots of tears.

In the years that followed we tried everything we could to help. This is what I discovered - dyslexia is neurological in origin and not related to ability.

Traditional methods of teaching reading do not suit all children

Lots of information online can be confusing for parents and many of the tools and programmes advertised - like specialist glasses and balance programmes - are often expensive and I could find no clear scientific evidence to prove they work.

I thought a diagnosis of dyslexia would radically change how my son was being taught to read, but a diagnosis did not help the way I thought it would. So in desperation to help him I looked elsewhere.

A mother on a social media network for parents of children with literacy difficulties suggested I try a book which teaches children to read using a different approach.

We decided to try it and sought help from our friend Alison Davidson who knew the system and Margaret Appleton, a specialist teacher.

This time Shea was being taught to analyse different words with the same letters and sounds and was learning the rules behind it all.

He was breaking down and de-coding words rather than blending them letter by letter. Soon, Shea's reading started to improve.

'A long journey'

Dr Sharon McMurray, who heads up the SEN (special educational needs) Literacy Unit at Stranmillis College, Belfast, is an expert in dyslexia.

She said schools need to take into account the differences in children's learning profiles to prevent disadvantage by focusing on only one teaching method.

"Children should be taught to learn to read using a broad and balanced approach which includes the use of a systematic phonics programme, either synthetic or analytic, but preferably drawing on both of these phonic methods," she said.

"It is important that a range of other strategies are also used.

"For children who have working memory and/or orthographic processing difficulties a phonics only approach is insufficient to develop reading skills and can prevent progress."

It's been a long journey of encouragement, hard work and determination by Shea.

He's now in his final year of primary school, happy and is reading. As anyone with dyslexia knows, there are still difficulties to overcome.

Shea's story shows that, with the right intervention, children with reading difficulties can learn to read and, more importantly, they are definitely not stupid.

Stories in Sound: Mummy Am I Stupid? is on Saturday 19 September, BBC Radio Ulster, 12:00 BST, and also on BBC Sounds