The Irish Giant: Charles Byrne, my uncle and Hilary Mantel

- Published

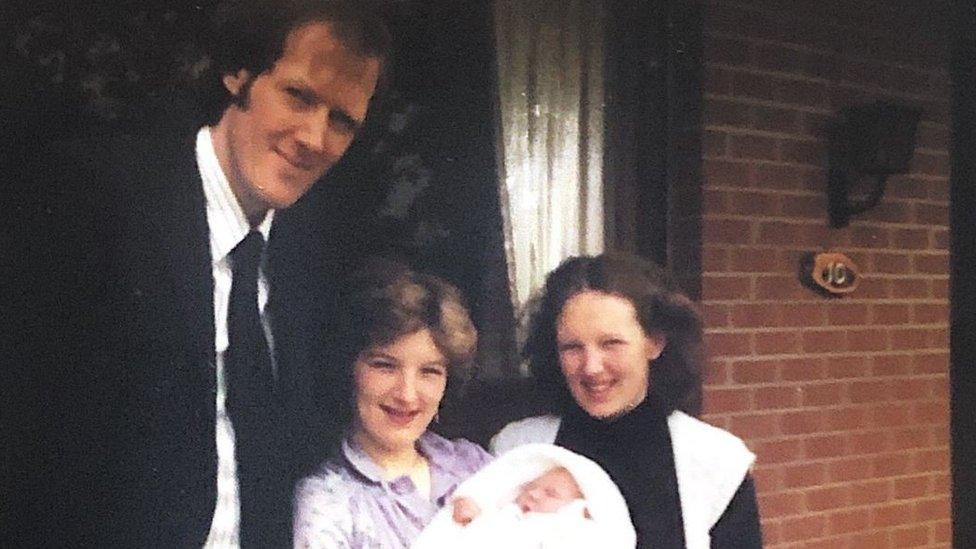

My uncle Brendan Holland with our distant cousin Charles O'Brien (Byrne)

Every family has a skeleton or two in the closet, but for mine it's in a museum display.

The plight of the remains of a distant cousin hit the headlines this week when celebrated author Hilary Mantel called for the bones of 'Irish Giant' Charles O'Brien to be released from a museum in London and returned for burial in his native mid Ulster.

Charles O'Brien was born in mid Ulster in 1761.

By 1782, his great height meant he was one of London's greatest celebrities, being paid to entertain audiences by displaying his 7ft 6in (2.3m) tall body under the stage name of Charles Byrne.

The legacy of this 18th Century celebrity is very much alive for my family in the form of my uncle, and godfather, Brendan Holland.

One of eight children born to my paternal grandparents in Killeeshil in County Tyrone he has stood out for most of his life.

Brendan was always tall and in 1972 at the age of 20 he reached 6ft 9-and-a-half inches (2.06m) in height.

Brendan (far right) aged 18 - the other family members are standing on a step

That year doctors at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London told him a benign tumour in his brain meant his pituitary gland was producing too much growth hormone and it was life-threatening.

Radiation treatment meant he stopped growing at 6ft 10-and-a-half inches (2.08m), but it took almost four decades for Brendan to find out why he had developed the tumour in the first place.

Mutated gene

In 2009, a documentary crew were making a film about O'Brien and another very tall man from mid Ulster was asked to take part.

It was only then that Brendan learned about Charles' life and came face-to-face with his skeleton in the Hunterian Museum.

The film-makers brought him back to St Bartholomew's Hospital where he met another doctor who would change Brendan's life.

Dr Márta Korbonits, a world-leading expert in growth hormone conditions had been working with O'Brien's DNA and believed both of them had grown so tall because of a "rogue" gene which had mutated.

Subsequent tests proved the O'Brien family and the Holland family shared a common ancestor about 1,500 years ago, and so the "Irish Giant" was a distant cousin of ours.

At my christening in 1980, Brendan became my godfather as well as my uncle

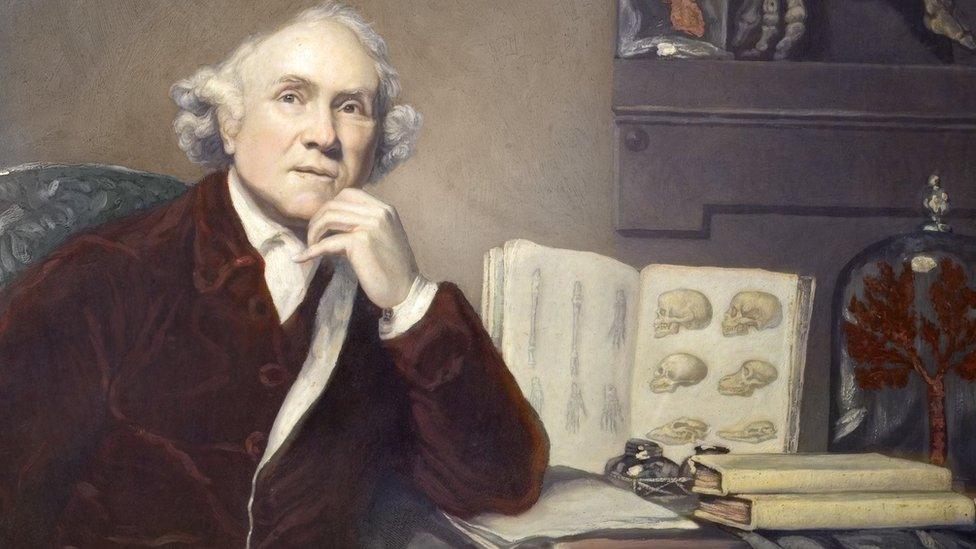

In the 18th Century, the Irish Giant inspired newspaper stories, plays and also one of the greatest surgeons and anatomists of the day.

John Hunter was known for collecting and displaying unique specimens for his museum and as O'Brien's health began to fade the surgeon offered him money for his corpse.

In June 1783 at just 22 years old, Charles O'Brien died and despite the best efforts of his friends to carry out his wishes to be buried at sea, Hunter managed to acquire the body.

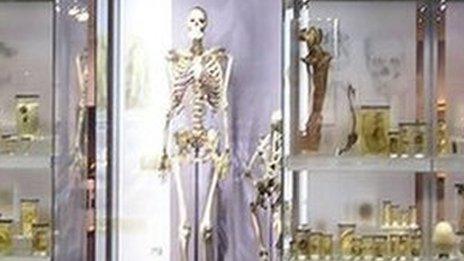

The skeleton of the Irish Giant later appeared in Hunter's private collection and then spent more than two centuries on public display at the Hunterian Museum in London which is run by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Ethical questions about the display of Charles' body have been raised many times and there have been frequent calls for his remains to be sent to mid Ulster, or for burial at sea.

In 2018, the Hunterian closed for renovations.

It is not set to reopen until 2022 and the museum said "plans for all the displays in the new museum will be issued in due course".

John Hunter, the Scottish surgeon and anatomist who put Charles O'Brien's body on display

Author Hilary Mantel published a fictionalised account of O'Brien's life in 1998 and recently told the Guardian "it's time Charles went home", external.

"I think that science has learned all it can from the bones, and the honourable thing now is lay him to rest," she said.

Initially I agreed wholeheartedly with that statement, but my uncle said it wasn't that simple.

Since 2009, Brendan has worked with Dr Korbonits to help identify others who could be affected by the condition in mid Ulster.

Three of his brothers and five of his nieces have the gene, and for Brendan the health benefits of knowing that is the "real payback" of having access to O'Brien's skeleton.

But how does he feel about O'Brien being kept in a glass case?

"One of the primary reasons they are on display, is so medical students can study the characteristics of excess growth. His bones are the perfect example of that."

He added: "If the experts were to say to me, 'that's it we aren't going to find anything more out from the skeleton', I would be happy to go along with that."

Brendan Holland spoke to the BBC in 2016 about gigantism

I had assumed Brendan would support the call for the skeleton to be released from the museum, that he would have been horrified by the thought of ending up in a similar position in 300 years' time.

"I'm a firm believer in the Scottish saying 'when you're dead, you're dead," he joked.

"We've had the same problems. I'm the lucky guy that was treated and was able to lead a normal life.

"If he knew his body would have been so useful in curing the problem that he lived with and suffered so much with, I think he would be quite happy about that.

"It's a difficult question and I'm not qualified to answer it, but I'm a bit more qualified than perhaps Hilary Mantel is."

- Published8 February 2013

- Published12 October 2016

- Published12 October 2016