Covid-19 decision dysfunction mars Stormont's report card

- Published

First Minister Arlene Foster and Deputy First Minister Michelle O'Neill lead an executive that has come under fire for its decision making

During a visit to a school on Tuesday, external, Northern Ireland's First Minister Arlene Foster said if she had to mark the Stormont government's theoretical report card on Covid-19, it would state: "Could do better."

With that in mind, how might the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader rate the performance over the past 48 hours, given the dysfunction that has played out?

On Thursday night, Stormont's power-sharing government decided to impose a new circuit-breaker lockdown for two weeks from next Friday, to try to curb the spread of infection.

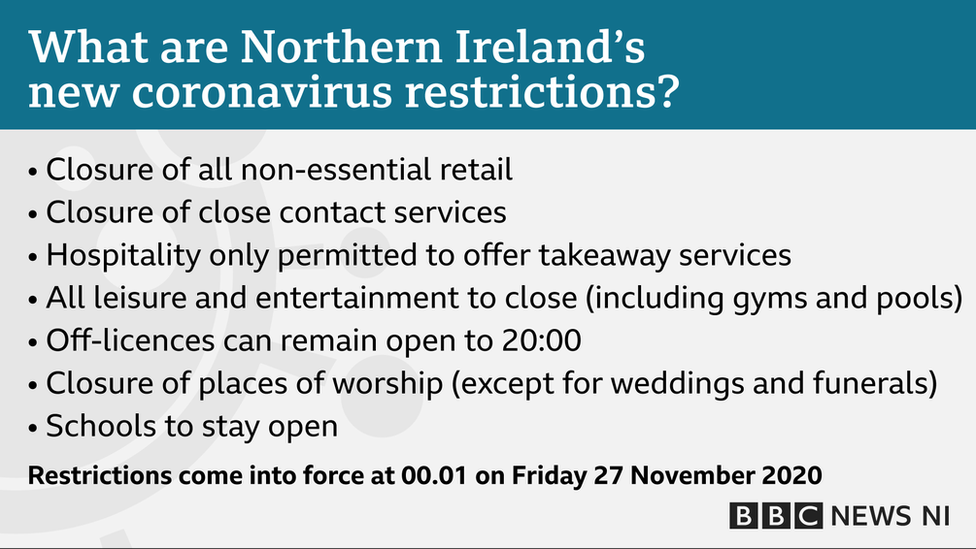

The measures - including the closure of shops, restaurants and most church services - are almost as strict as those of the first lockdown, although schools and childcare providers will remain open.

Just a week earlier, the DUP - then the most vocal opponents of more measures - had blocked two less extreme proposals to extend restrictions, arguing reopening the hospitality sector was crucial for Northern Ireland's economy.

Questions remain about why the party changed its mind so suddenly - and dramatically.

Along with nationalists Sinn Féin, the DUP co-chairs the NI Executive, which is made up of five parties who work in a mandatory coalition, sharing power to ensure equal representation for unionist and nationalist communities.

Hours before Thursday's executive meeting, the tone of senior DUP MPs shifted, as they argued Northern Ireland's situation had changed with medical evidence presented to the executive this week meaning tighter restrictions were required.

But the Department of Health's paper, external, given to ministers on Tuesday 10 November, stated that Northern Ireland's R-number - or rate of transmission - was sitting at 0.8 "and rising", while health officials were also warning that pressure on hospitals looked set to worsen.

Other executive parties also reject the DUP's assertions about a change in medical evidence and point out that health officials had initially proposed a six-week lockdown - including four weeks of school closures - as far back as mid-October.

So how to account for the DUP's 180-degree shift in position?

Senior party figures met last weekend and it's thought there was concern the DUP could find itself on the wrong side of the argument and be blamed, if figures rocketed or health service pressures became too much.

It's never a good thing for one party in the executive to be isolated on an issue - and the DUP had found itself in that position having triggered a cross-community vote twice on a public health matter.

Three or more ministers can ask for a vote to be taken on a cross-community basis, which effectively gives parties like the DUP, with enough ministers, a veto.

Mrs Foster and other DUP members have defended its use, but going into Thursday's meeting it was clear the party was not going to deploy it again, aware of the political backlash they had already faced.

'Scathing criticism'

It's perhaps coincidental, but not insignificant, that the DUP's former leader, Peter Robinson, wrote in his News Letter column on Friday, external that the vetoes should be done away with - an argument some executive parties would happily support.

There was also recognition of just how badly the previous week's events had damaged relations at Stormont, with some sources remarking that the situation was almost beyond repair.

While there's been a collective sigh of relief that executive spats didn't repeat themselves so publicly this time, the decision has left many wondering why there were such heated disagreements last week?

Among those asking questions are business representatives, who have been scathing about the executive's lack of communication.

Ministers met throughout Thursday as an agreement began to take shape, but some in the retail sector only found out from the media that the executive was preparing to close non-essential shops.

All non-essential retail will close for two weeks from Friday 27 November

At about 18:00 GMT, the executive met again to consider formal recommendations from Health Minister Robin Swann, and journalists were told a statement might be released by 19:30.

Interview requests rejected

News of what had been agreed began to leak to journalists at about 20:15 - but despite the agreement's magnitude, no joint press conferences or interviews were planned.

A statement from the Executive Office, external confirming the new measures was not released until almost 22:00 and it wasn't until 08:56 on Friday that the first executive minister, Justice Minister Naomi Long, featured on BBC's Good Morning Ulster radio programme.

It is understood the executive meeting had ended shortly before 20:00, with a presumption that some ministers were preparing to do a short media briefing. But this never materialised, despite the executive being told that all ministers needed to do some "heavy lifting" to sell the plan via media outlets.

Sinn Féin's Michelle O'Neill said ministers had "missed the evening news cycle"

Deputy First Minister Michelle O'Neill's explanation, when she spoke to reporters on Friday, was that the executive meeting had run late and "missed the evening news cycle", but that she had outlined what had been decided via social media.

One irate businessman labelled the executive "numbskulls" for appearing to be unable to manage their approach properly.

Meanwhile, the executive continues to struggle with the challenge of ensuring compliance with the rules.

Amid the calls for the executive to act quickly, all parties want to make sure they're making the right decisions.

Health officials are relieved by the new restrictions, which they hope will provide the "breathing space" they called for several weeks ago. But they're also acutely aware of the resulting social and economic ramifications.

'No promises'

And while businesses will find the next few weeks - their most important trading season - difficult, they know the uncertainty will continue, with no details yet of extra financial support promised by the executive.

The lockdown measures are due to end on 11 December but, this time, no ministers are promising that this date is set in stone.

Rather, they say, it represents the "best chance" of getting Northern Ireland to Christmas.

Despite all the pressures, there are some hopeful flickers of light: The Department of Health has said Northern Ireland will be in line for 4.35 million doses of vaccine, possibly as early as next month.

The last week has proved a tough lesson for the executive. Its members will hope that when it comes to their end-of-term report card, this will be upgraded to say: "Making good progress."

- Published20 November 2020

- Published11 January 2021

- Published19 November 2020

- Published20 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023