Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell: Portrait honour for 'trailblazing' NI scientist

- Published

A portrait of Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell has been unveiled by the Royal Society in London

A leading astrophysicist, who was once overlooked for a Nobel prize in favour of her male collaborators, has now taken her "rightful place" among the world's most distinguished scientists.

A portrait of Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell has been unveiled by the Royal Society in London, in tribute to her "trailblazing" contribution to science.

On this day in 1967, she discovered a new type of star known as a pulsar.

At the time, she was a 24-year-old student studying for her phD.

The Royal Society, a fellowship of hundreds of the world's most eminent scientists, described pulsars as "one of the greatest astronomical discoveries of the 20th Century".

More than half a century on from her breakthrough research, the Northern Ireland-born astrophysicist said she was "really pleased" to be honoured by her peers with a formal portrait.

"I think personally it's very important that women are represented," Dame Jocelyn told BBC News NI.

She said that although female representation was "growing", women were "still a small minority in the Royal Society".

The society commissioned the painting as part of its project "to increase the number of female scientists" in its art collection depicting its fellows and presidents.

"They've been mainly male up to now," Dame Jocelyn told the BBC's Today programme.

"And it's 75 years since women were admitted, so they're not exactly rushing it, are they?"

She was a young post-graduate student at the University of Cambridge when she first observed the phenomenon of pulsars.

The then Dr Jocelyn Bell Burnell, photographed in 1977

Pulsars are rapidly spinning neutron stars, so named because they appear to pulsate when viewed from Earth.

They emit a beam of electromagnetic radiation, which can only be detected when the beam shines on our planet.

'Little green man'

As a research assistant in the late 1960s, Dame Jocelyn was part of a team who built a large radio telescope in a field outside Cambridge to monitor quasars - some of the brightest known objects in the universe.

"It was to be operated, full-time, by one person - a girl," the BBC's Horizon programme reported, a little incredulously, in 1971.

The programme documented how the young student was reviewing printouts of the quasar experiments when she noticed a regular radio pulse in the graphs.

She and her supervisors jokingly referred to the pulse as "little green man" as they tried to work out where the patterned signal was coming from.

Paper printouts stretching over three miles long were painstakingly examined before Dame Jocelyn "satisfied herself that this was a star that ticks like a clock" according to Horizon.

No Nobel for Bell-Burnell

Three years after that broadcast, Dame Jocelyn's phD supervisor Antony Hewish and radio astronomer Sir Martin Ryle were jointly awarded the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Hewish was recognised by the Nobel committee "for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars" but Dame Jocelyn's contribution was overlooked.

Her omission was immediately questioned by leading scientists, but she has argued the prize was awarded appropriately at the time due to her student status.

In more recent years, the science community has been making up for the 1974 snub, but she continues to be diplomatic when asked about the controversy.

Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell donated £2.3m to help people from unrepresented groups study physics

"If you don't get a Nobel prize, you can actually do rather better," she told the Today programme.

"Whereas if you get a Nobel prize, people feel that they can't match it and you get nothing thereafter.

"So I've been in the wonderful position of having a party most years, or every few years, as I get yet another award. So it's been pretty good."

In 2018, Dame Jocelyn won the Breakthrough Prize for the discovery of radio pulsars, a major science award with prize money of £2.3m.

She donated her winnings to help more people from under-represented groups become physics researchers - including women, people from ethnic minority backgrounds and refugee students.

'Imposter syndrome'

The astrophysicist believes her own background as a woman from Northern Ireland spurred her on to achieve at a young age.

Dame Jocelyn was born in Belfast in 1943 and grew up in Lurgan, County Armagh.

She attended Lurgan College in the town, before moving to England at the age of 13.

"I reckon that my discovery of the pulsars came about because I was suffering imposter syndrome," she said.

"I was in Cambridge as a woman from the north and west of the country at the time when most of Cambridge was affluent, south-east England males.

"So I felt very much an outsider - I was quite convinced they were going to throw me out at some point and decided I'd work really hard, until they threw me out, so that I wouldn't have a guilty conscience."

Asked by BBC News NI if she thought her omission from the Nobel prize was more to do with her gender than her student status, she replied: "I think it was probably a bit of both, to be honest."

Dame Jocelyn has enjoyed a high-profile academic career and, in 2014, she was appointed the first female president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science.

She is currently a professorial fellow in physics at Mansfield College, Oxford and she has been a member of the Royal Society since 2003.

'True role model'

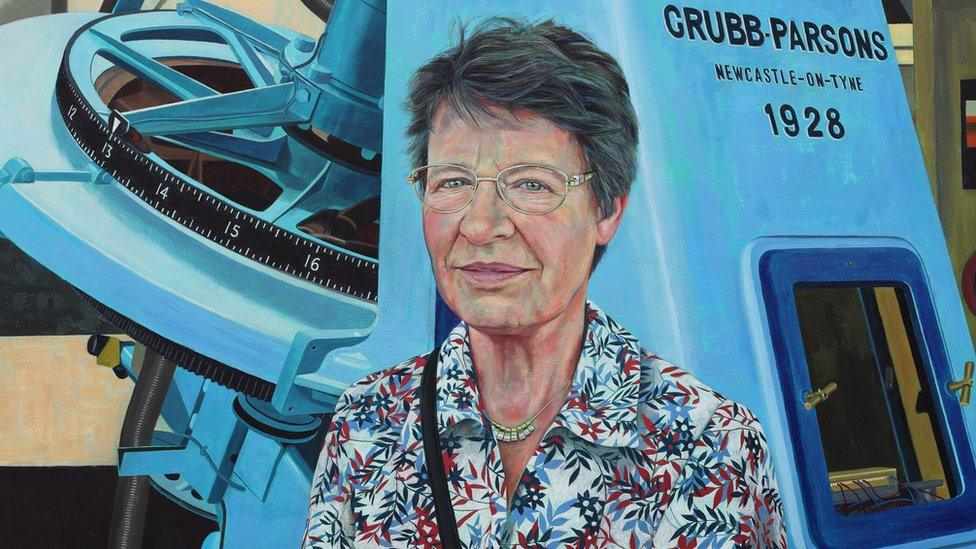

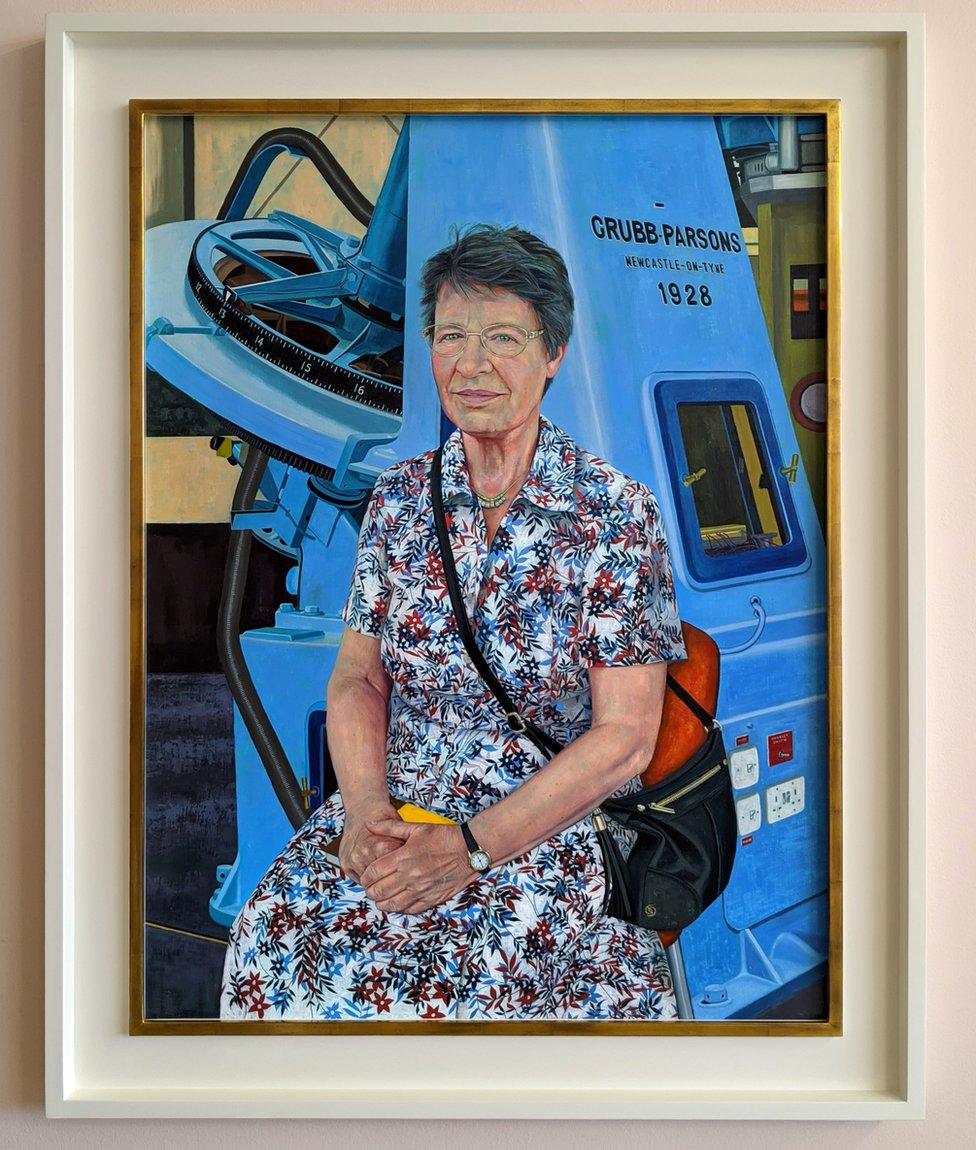

To mark the 53rd anniversary of her breakthrough discovery, the society commissioned an oil painting of Dame Jocelyn by artist Stephen Shankland.

The portrait will be displayed at the Royal Society's London headquarters

It will be displayed at the top of the grand staircase in the society's headquarters in London.

"We are very excited that Dame Jocelyn's portrait will take its rightful place beside those of the most distinguished scientists of all time," said Keith Moore, head of its library, art and archive collection.

He described her as a "true role model".

"Not only has she made a ground-breaking contribution to astronomy, but has supported the future of science by generously helping young people, who may feel marginalised, to work in the field of physics.

"We hope her portrait will inspire these young scientists to feel that they too could become the Dame Jocelyns of the future."

- Published5 February 2014