Brexit and Northern Ireland - the year in review

- Published

Questions about the post-transition trade border were not answered until late in the year

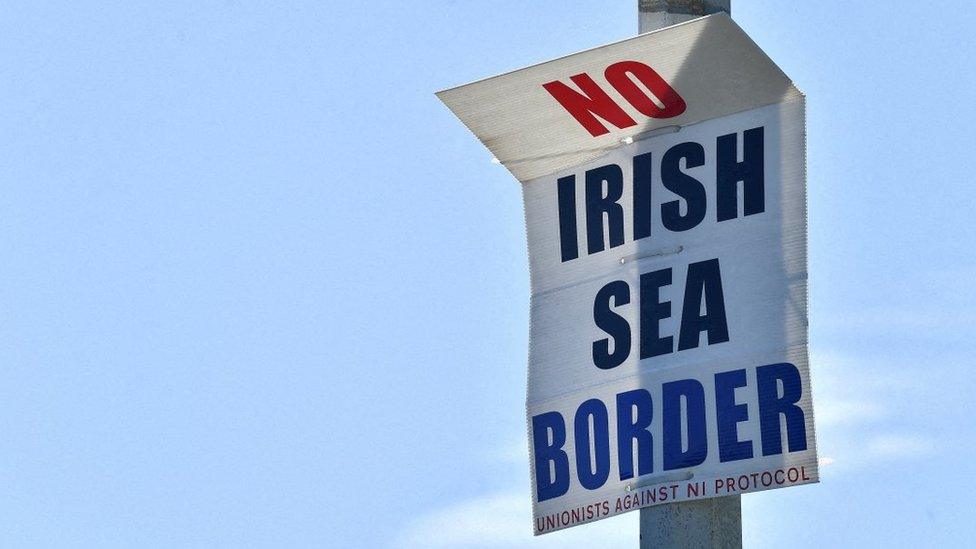

For much of 2020, the UK government appeared reluctant to acknowledge what it had agreed on Northern Ireland in 2019.

In August, Prime Minister Boris Johnson was still saying there would be an Irish Sea border "over my dead body".

Later, his government was prepared to break international law to unwind parts of the agreement before finally reaching an accommodation with the EU.

The year began with a triumphant Mr Johnson getting his withdrawal agreement through Parliament and delivering Brexit.

The UK immediately entered a transition period during which it continued to follow EU rules while negotiating a new long-term relationship.

Boris Johnson struck a bong to mark the UK's departure from the EU on 31 January

The transition period was also to be used to "operationalise" the Northern Ireland part of Mr Johnson's deal, known as the protocol.

The protocol keeps Northern Ireland in the EU's single market for goods and also means EU customs rules will be enforced at Northern Ireland's ports.

This requires new checks and processes for goods entering Northern Ireland from other parts of the UK, effectively creating a trade border.

Early divide in Joint Committee

The UK and EU had to negotiate the nature and extent of those checks and controls.

This negotiation happened through a body called the Joint Committee, chaired by Cabinet Office Minister Michael Gove and EU commissioner Maroš Šefčovič.

It did not meet formally until the end of March and the most notable of its early exchanges was a row about the nature of the EU's future presence in Northern Ireland.

Michael Gove and Maroš Šefčovič led negotiations about implementing the withdrawal agreement

Meanwhile, the civil servants who would have to implement and operate the sea border were anxiously waiting for instructions.

It wasn't until 20 May that they could really begin work with the publication of a UK command paper.

That was effectively an implementation plan, albeit one that hadn't been agreed with the EU.

Building the border

It was the government's most explicit acknowledgement that new facilities would be required at Northern Ireland's ports for inspecting goods arriving from other parts of the UK.

It pledged to spend more than £300m on a Trader Support Service to help businesses with the millions of customs declarations which would be needed on GB-NI trade.

By July, the government had submitted applications to the EU to create border control posts at Northern Ireland's ports.

But even then civil servants couldn't get on with getting them built.

Contractors have been racing to get border control posts ready at the ports in Belfast, Larne and Warrenpoint

The responsibility for delivering these posts fell to Stormont's Department for Agriculture, as the facilities are used for inspecting food and animals.

That department's minister is the Democratic Unionist Party's (DUP) Edwin Poots, no fan of a sea border.

He became embroiled in a dispute with the UK's agriculture secretary, saying he needed more information about how the posts would be used.

By the autumn, it was clear there would be no time to get new facilities built and Mr Poots' officials have since been scrambling to get temporary arrangements in place for 1 January.

'Very specific and limited way'

The Joint Committee continued its work with little public comment on what was or wasn't being agreed.

Then in September, Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis made a dramatic intervention.

Brandon Lewis says Northern Ireland customs rules legislation do “break international law in a very specific and limited way”

He told the House of Commons that the government was bringing forward a piece of legislation, the Internal Market Bill.

That bill, he said, would break international law in a "very specific and limited way" by overriding some parts of the Northern Ireland deal.

That was aimed at two parts of the deal where the UK believed the EU had over-reached.

First, the insistence that Northern Ireland goods would need a piece of administration known as exit summary declaration when being sent to Great Britain.

That was in conflict with the prime minister's pledge that Northern Ireland businesses would have unfettered access to Great Britain.

Secondly, the UK had come to regret the part of the Northern Ireland deal on state aid - the financial support governments give to businesses.

It feared the state aid part of the deal was drafted in such a way that the EU could use it to interfere in broader UK measures, such as business tax cuts, that also have an impact in Northern Ireland.

The deal is done

The UK move caused outrage among EU leaders and later US President-elect Joe Biden expressed his concern.

But the talking did not stop and by December Mr Gove and Mr Šefčovič had a deal.

The UK could be satisfied - the EU had dropped the insistence on exit declarations and the state aid provisions had been clarified.

Michael Gove (left) and Maroš Šefčovič announced their agreement in December

Additionally, the prospect that many goods from Great Britain could face a tariff when entering Northern Ireland had been largely resolved through a new trusted trader scheme.

The EU was also content that its officials would be present in Northern Ireland to oversee the implementation of the new sea border checks.

The law-breaking clauses of the Internal Market Bill were dropped.

The government announced a series of measures aimed at making the introduction of the new sea border as painless as possible.

We will soon know if those measures have worked.

- Published2 February 2024

- Published8 December 2020

- Published8 September 2020