Mother-and-baby homes: 'They called us fallen women, bad women'

- Published

Adele had herself been adopted from a mother-and-baby home in Belfast in the 1950s

Adele is almost 70 - but even now she said the smell of lavender wood polish triggers a memory rewind of more than half a century.

Aged 17, she was brought to Marianvale mother-and-baby home in Newry, County Down.

She had been taken in her parish priest's car after discovering she was pregnant.

Once she arrived, Adele said the nuns who ran the institution took away her name.

"They said I could no longer use my ordinary name, and I was given a name to use while I was there," she explained.

Adele herself had been adopted from a mother-and-baby home in Belfast in the 1950s, after being born to a single mother.

Her adoptive family were "good people" but she feels "there wasn't a lot of affection and love in the household".

She said she "looked for love in the wrong places".

'Dance like monkeys'

The journey to Marianvale was "frightening", she said.

"I didn't know what was going to become of me."

Aside from the distinctive odour in the home's main hall, Adele remembered being brought to meet the other girls with whom she would share a dormitory.

They were told not to tell each other about their own circumstances - but "of course, we did talk".

Life in the home was "very austere, very regimented".

She worked in the kitchen, and scrubbed floors on her hands and knees.

Later, she cleaned a family home, but was given no wage.

Nuns "repeatedly called us fallen women, bad women - told us we had to pay for our sins".

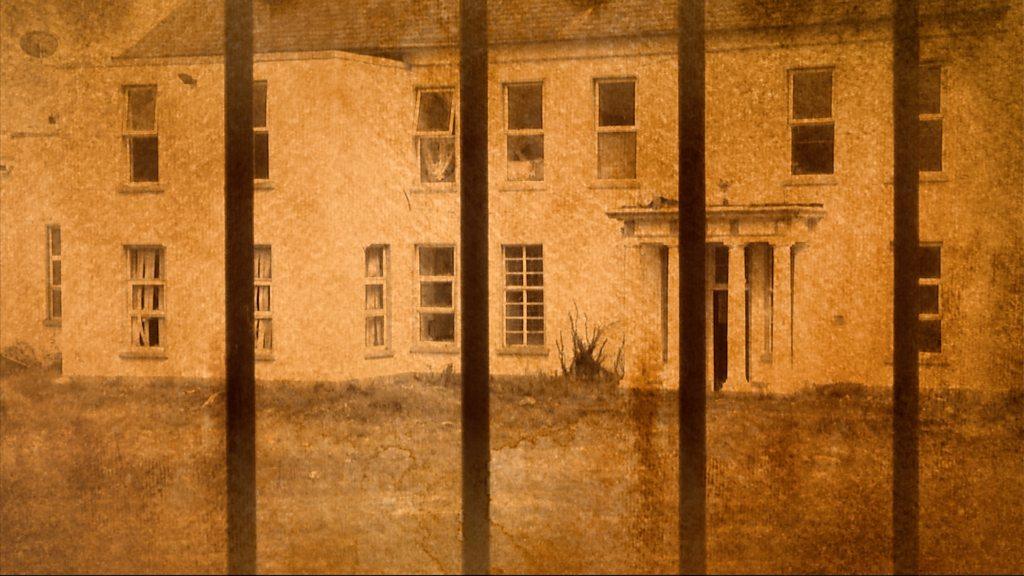

The former nuns' residence at the Marianvale mother-and-baby home in Newry, County Down

One memory seems to sting particularly sharply: "On one occasion, we had to put on a show for them.

"I can't remember whether it was St Patrick's Day or Easter.

"We had to dance like monkeys for their entertainment.

"It was horrendous, and it will stick in my head until the day I die."

'I can die now'

She gave birth to her son in hospital in Newry - an experience she described as "traumatic" and "lonely".

Adele returned to Marianvale with her boy.

"I had been told by my family and the nuns, in no uncertain terms, that the baby was going to be adopted," she said. "I was given no other option."

After a few months she was told the adoption arrangements were in place and she was to get the baby ready.

"I dressed him in some of the clothes which I had knitted and some of the things I had bought," she recalled.

"I wrote a little letter and I hid it at the bottom of the bag to send to his adoptive parents, telling them a little about me.

"Then I carried him down a corridor, handed him to a nun, and that was the last I saw of him for forty years."

This is the point in Adele's powerful, brave story when she is the most visibly emotional.

'Guilty secrets'

She went back to her family and her child was never mentioned in the house again.

Later she married and had more children.

Ten years ago, her first child made contact with her and she went to meet him in a hotel.

"I had so many feelings, it was frightening, it was exciting, it was upsetting.

"It was so marvellous to see the baby I had given birth to, now a grown man and the connection was there immediately, on both sides."

She has met his wife and children.

She had always wanted to know what his life was like: "Was he loved? Did he have a decent home?"

She found out that he had "a good life" during their first meeting and remembered saying to herself: "I can die now, I'm happy."

Marianvale was one of a network of mother and baby institutions in NI and the Republic of Ireland

She wants a public inquiry into the institutions for unmarried mothers in Northern Ireland and for those who ran them to be held to account.

"They took our dignity. They took our rights. They took our freedoms.

"You have to shine the bright light of truth upon this; it's no longer acceptable for them to hide in the shadows and for us to hide guilty secrets.

"They're not guilty and they're not secret any more."

The people who were born in the homes also want accountability and answers.

'Sort of made-up'

Mark McCollum was born in Marianvale in 1966 and then taken across the border to an orphanage in County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland.

He said the fact he was taken out of one jurisdiction and adopted in another, where laws were different, was "not right on any level".

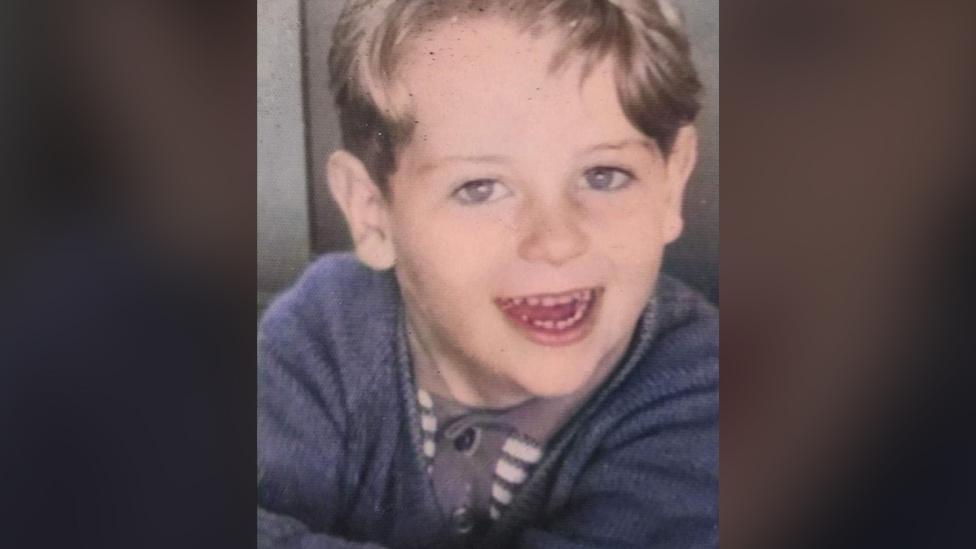

Mark McCollum found out his birth mother was Kathleen McGuire from Londonderry

Mark stressed he had a "fantastic" upbringing with a loving adoptive family.

But he said he had been "looking for his identity" his whole life.

Last year, he obtained his birth certificate for the first time.

It showed him he had been named Paul Anthony McGuire.

He said Mark McCollum "is sort of made-up - he doesn't have a birth certificate".

I first spoke to Mark in 2018, for a report on BBC Radio 4's PM programme when he was trying to trace his birth mother.

A few months ago, he discovered her identity.

She was called Kathleen McGuire and was from Londonderry - "a wee Derry girl, she worked in the factories".

She moved to the north of England.

Mark found out she "died young" and that he was her only child.

Mark McCollum said the church and state should make reparations for what happened

"It was lovely to find her, but it's also bittersweet because I was denied the right to information which would have allowed me to do that 20 or 30 years ago.

"You kind of think, things could have been different."

He said the institutions were similar on both sides of the Irish border - "they had the same purpose, to punish the girls for their sin".

"The church at the time was looking at Ireland as a single state.

"That was the rationale about moving babies from Marianvale over to Donegal, they didn't see anything wrong with that."

PJ Haverty explains what life was like for him after being born in Tuam mother-and-baby home

Poignantly, he said: "We, the babies, were the physical embodiment of sin. We weren't regarded as being worthy of love and affection, because we were spoiled fruits."

He believes there should be a public inquiry and that the Stormont Executive should commit to implementing its recommendations.

Mark also wants memorials to be created and for the church and state to make "reparations" for the stigma and misogyny suffered by women like his mother.

"This was going on for seventy years," he said. "It was a complete abuse of power."

Independent inquiry

Solicitor Claire McKeegan, who represents the group Birth Mothers and Their Children For Justice NI, said she expected the research would reveal "a litany of human rights violations" and "an appalling scandal".

She points to a series of investigations which have been held over the course of a number of years into institutions in the Republic of Ireland, including mother-and-baby homes and Magdalene Laundries, where women branded as "fallen" were forced to do unpaid labour in oppressive conditions.

The research commissioned by the devolved government in Belfast, which has been carried out by Queen's University and Ulster University, has examined both types of institutions in Northern Ireland.

Ms McKeegan said: "The abuse of women and babies did not stop at the border.

"The state in Northern Ireland not only permitted what happened, but also policed it.

"It is critically important that an independent and prompt inquiry now takes place, to allow these women to have truth, justice and redress."

Tens of thousands of people, in both Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, have been affected by the past practices of moral exile and institutionalised shaming.

And given the last homes closed only in the 1990s, this is not "history" to many people.

Survivors, and their families, live with the legacy every day.

- Published13 January 2021

- Published12 January 2021

- Published14 September 2020