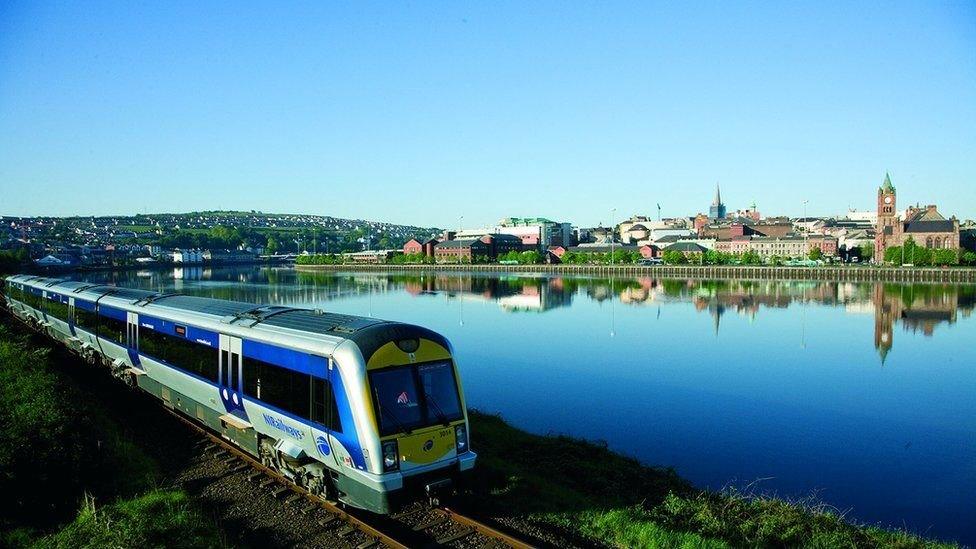

Northern Ireland's railways: What happened to the network?

- Published

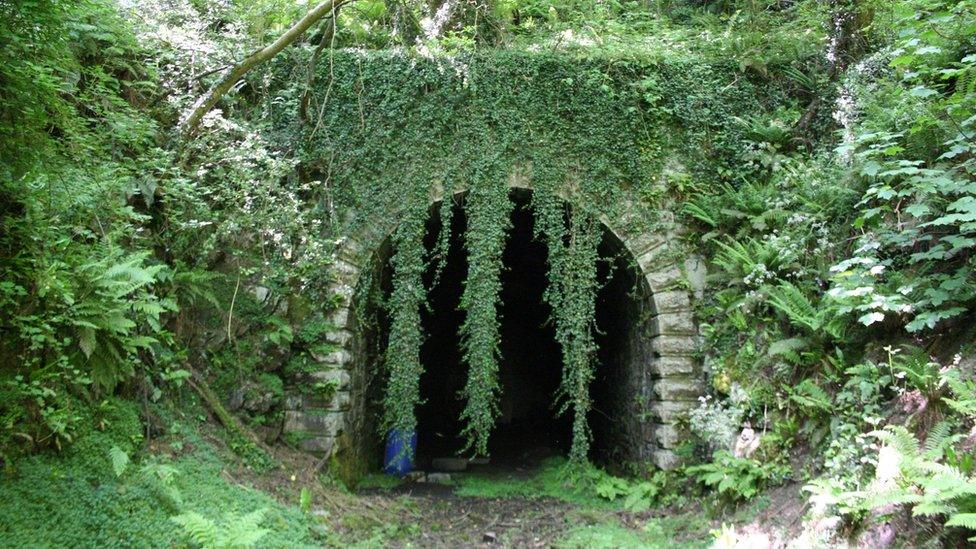

Nature reclaims the overgrown Lissummon Tunnel

There was a time when almost everyone in Northern Ireland lived within five miles of a railway station.

More than 750 miles of track once linked towns and communities in every county, but most of this infrastructure was abandoned in the 1950s.

A new review into an all-Ireland rail network was announced in April to look at the possibility of reviving the golden age of rail travel.

But why did Northern Ireland's rail network disappear in the first place?

The creation of a border led to huge delays for passenger trains

Railway historian Charles Friel, a member of the Railway Preservation Society of Ireland, said the decline began after the partition of Ireland in 1921.

"Partition disrupted trade on many natural routes, Donegal and Sligo to Londonderry for instance," he said.

Mr Friel said the creation of a border led to huge delays for passenger trains traveling from one side to another and goods trains were subject to extensive paperwork and regulation.

Administrative problems at the border were further compounded by increased competition from road vehicles after World War One.

"Lots of people came back from the trenches knowing how to maintain and drive lorries, many of which had been shipped back from the front line and converted for haulage or into busses," Mr Friel said.

Jewel in the railway crown

Transporting goods by road became an appealing proposition for businesses and companies began using their own vehicles rather than loading goods on and off trains.

"The expense became in the handling," Mr Friel said, "and lorries reduced the handling and labour costs by half."

The former station at Newcastle, County Down, in the shadow of the Mourne Mountains

Many architectural ghosts of Northern Ireland's lost rail heritage can still be found across the country, long after the tracks were lifted to make way for roads and other new developments.

The former station at Newcastle, which was once the jewel in the crown of the County Down railway system, is now a supermarket. It previously passed through Castlewellan, Saintfield, Dundrum and branched off at Downpatrick for Ardglass.

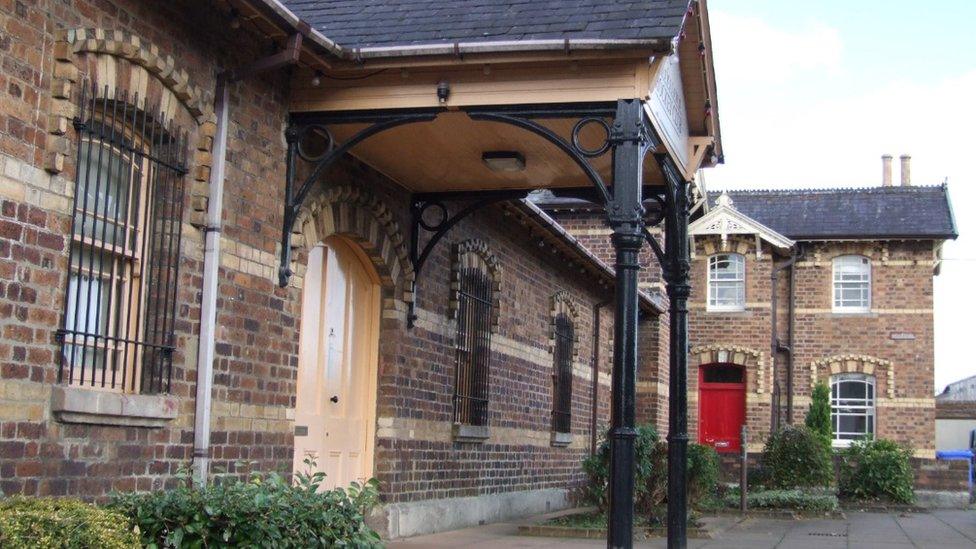

The former station at Cookstown, now occupied by the local hockey club

In Cookstown, County Tyrone, the listed railway station designed by William Henry Mills in polychromatic red and yellow brickwork, was closed to passengers in 1956.

It is now home to Cookstown Hockey Club.

Much of the building's railway heritage has been left intact, including the buffers, part of the original track and the platform, which is now used as a beer garden.

Chairperson Colin Scott said the club has always enjoyed close links with the railway.

"The railway line used to run right next the pitch," he said.

Reclaimed by nature

"If players travelling by train were ever late to a match, the train would stop to let them jump off and run across the field into position."

Mr Scott said his family, who arrived in Cookstown in 1887 and have remained ever since, "would never have come to the town if not for the trains".

A disused railway bridge in County Armagh, slowly being reclaimed by nature

Some of Northern Ireland's abandoned rail network has been absorbed by its surroundings, overgrown almost beyond recognition.

But Jonathan Hobbs of NI Greenways believes the development of walking and cycling routes along former railway track beds can help to preserve even the most neglected sites, possibly paving the way for future rail infrastructure.

A former railway line in County Armagh

"I'm dead-set against the idea that rail and greenway development is mutually exclusive," he said.

"I see it as being two sides of the same coin - greenway development is a really good first bet and should move out of the way when rail becomes a viable option."

Mr Hobbs said there are very few areas in Northern Ireland that could not accommodate both a railway track and an adjacent greenway.

"There can definitely be synergy between the two but, where it is possible to open railway lines, that really should be the priority," he said.

A train travelling past Belfast International Airport on the mothballed Knockmore line

Despite being out of service for many years, some rail infrastructure is still very much intact.

The mothballed Knockmore line from Lisburn to Antrim, which travels through Crumlin and past Belfast International Airport at Aldergrove, is a notable example.

Robert Gardiner, chairman of the Downpatrick and County Down Railway, said there is still potential for traffic on this route should it reopen.

"People say there are no rail connections at any of our airports," he said.

"Actually, all of them have a rail connection - you just can't get off at them.

"If the Knockmore line was open you could wave at the end of the runway at Aldergrove," he said.

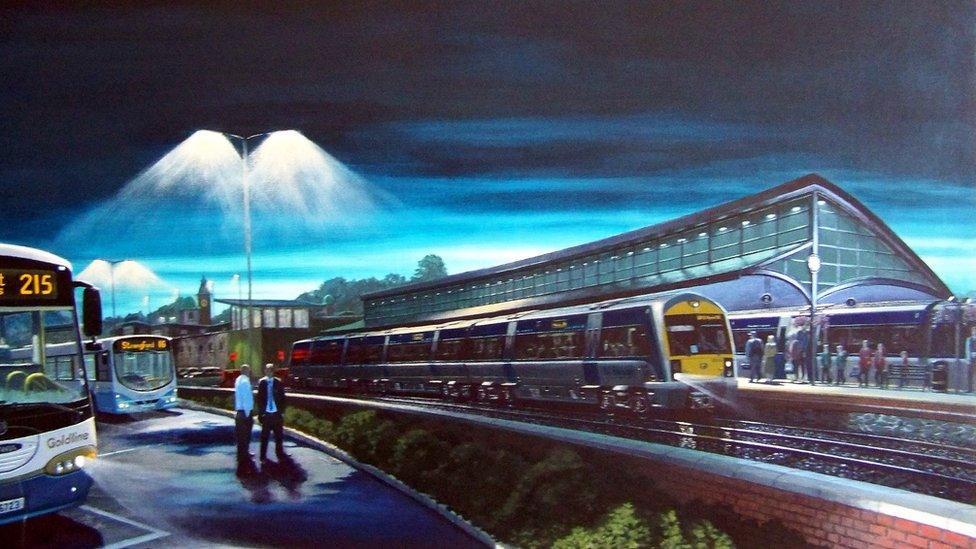

What a railway station in Downpatrick could look like today if the line was still in place

The Department for Infrastructure (DfI) told BBC News NI it "cannot pre-empt what recommendations come from the review" into an all-Ireland rail network.

Mr Gardiner said a good starting point would be to reverse some of the damage already inflicted on Northern Ireland's railways.

"While there are many people who would like to see the network extended, especially where there is a clear demand from the community, there's still an awful lot of work to get the existing network back up to full capacity," he said.

Mr Gardiner said it would be unrealistic for residents of every town in Northern Ireland to have easy access to rail in the future, but believes there is some optimism to be drawn from DfI and the Irish Department of Transport working together on the current all-Ireland review.

He said: "It's the first time since partition that there's been a holistic, governmental look at what we have in terms of rail across the island of Ireland."

Related topics

- Published16 September 2020

- Published7 April 2021