Hospitality: Staff shortages as sector reopens in Northern Ireland

- Published

- comments

Businesses are facing staff shortages as the hospitality sector reopens in Northern Ireland.

Hospitality Ulster said recruitment challenges that existed pre-Covid have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

"Post-covid there is a shortage of available staff," said Colin Neill.

"Our pubs were shut for a year, people have gone to another job and got settled and there is also a lack of confidence about how long hospitality will be back for."

The Job Retention Scheme, now often referred to as furlough, allowed employees in restricted industries to claim 80% of their wage, up to a maximum of £2,500 a month, while lockdown measures were in place.

Mr Neill said it had been necessary to help people through an uncertain time, but many have now settled into other jobs.

"Furlough, it was important as people needed money, but then they got something else.

"People are asking - will we be shut again and what will happen next?"

Colin Neill of Hospitality Ulster said that post-Covid there is a shortage of available staff

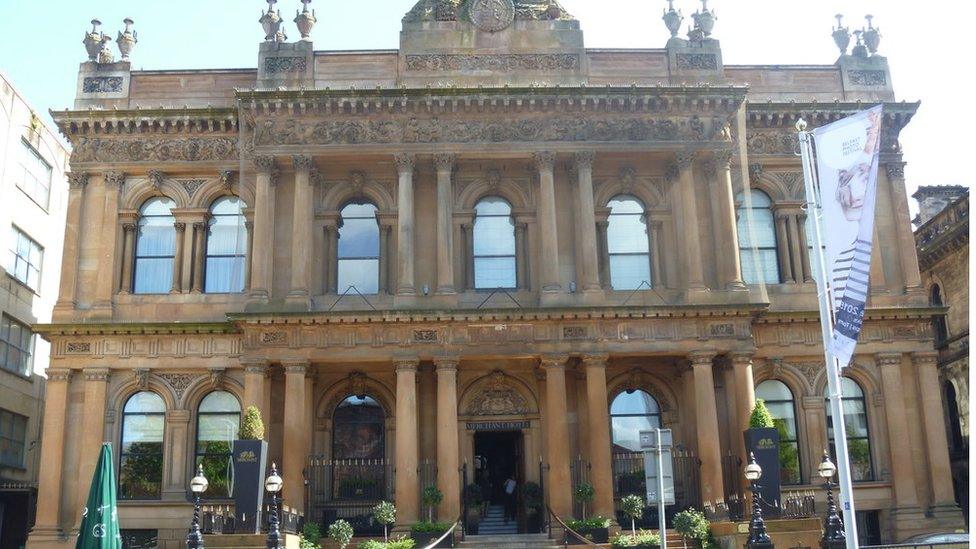

Conall Wolsey, of the Beannchor Group, said before the pandemic they employed 800 people, but have since then lost about 20% of their staff.

He said they had been able to fill about 50 of those positions, but 100 positions remained unfilled.

"Unfortunately we have just had to reduce some of our services - that might mean we can't open seven days a week in some of our venues," he added.

The Merchant Hotel is part of the Beannchor Group

"We've reduced back to Thursday-to-Sunday trade and unfortunately I think it's going to be a wee bit of short-term pain for us, opening hours wise, and obviously that will affect us and our turnover.

"I suppose the number one priority for us is giving people a service that is of the standard we see and the only way to do that with our staff is not stretching our staff."

The coronavirus lockdown has also led some workers to reassess their lives.

Marty McAdam from Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, decided to leave his job as a head chef in a hotel to set up his own business called Street Kitchen so that he can be his own boss and work the hours he wants.

'The pandemic gave me a chance to step back'

"I've been in the industry now coming up to 20 years and just with Covid and the strange times that we've been in, it has kind of given me a chance to step back and think about what I want to do," he said.

"I decided at the end of last year that I was going to open up my own restaurant, so we're going to open a small 20-seater restaurant, we're going to do brunch and lunch and just with more of a chill vibe.

"I think it has given us a chance to just do whatever we want and not have to answer to anyone, or have to deal with the big mass numbers, because I think for me personally Covid has given me a bit more clarity in what I want to do in life."

But despite the long hours and hard work he says he could not envisage a complete change in career.

"The hospitality industry has given me opportunities and let me travel extensively," he added.

"It's one of the best trades you can get into and you can see the world and there's never a dull moment so I can understand why some people leave it but for me I don't think there's a better industry to be in."

Recruitment crisis

Neil Moore from Unite the Union, which represents some hospitality workers in Northern Ireland, said the pandemic had highlighted staff retention issues that already existed in the sector.

The union surveyed its members in the hospitality sector between August and November 2020.

"Forty per cent planned to leave the industry and 78% of chefs said they wouldn't recommend the industry to school leavers," he said.

Among the reasons listed for wanting to quit was low pay, long hours and a poor work-life balance.

"For us the recruitment and retention crisis that certainly existed before Covid, has only been deepened by workers having to live on 80% furlough, which is 80% of an incredibly low wage, and as a result of that, people want out," he said.

"The only solution in our heads is employers addressing this problem and making it attractive to a new layer of young workers with proper work-life balance, permanent secure contracts and a real living wage."

- Published24 May 2021

- Published24 May 2021