NDNA: What the deal means for NI language and culture

- Published

There is no new stand-alone Irish language act - the new legislation amends the existing Northern Ireland Act

The "cultural package" including Irish language laws have been at the heart of the Stormont stand-off and seemingly the row within the DUP.

But what was agreed on language and culture in the New Decade New Approach (NDNA) agreement?

Some parts of that agreement have already quietly been enacted, like an Irish and Ulster-Scots language translation service for public bodies.

There will be also be simultaneous translation into Irish and Ulster-Scots in the assembly.

But the bulk of the NDNA measures are still to come into force.

Office of Identity and Cultural Expression

There is, though, no new stand-alone Irish language act as the new legislation on language amends the existing Northern Ireland Act, 1998.

An "Office of Identity and Cultural Expression" is to be set up by the Executive Office under the NDNA plans.

It will be a statutory body and the First and Deputy First Minister, acting jointly, will appoint its director.

In many ways, they will be a kind of "cultural ombudsman" - guiding public bodies and monitoring how they provide services to users of minority languages.

More vaguely, they will also look at how "cultural traditions and identities" are being promoted and protected, as well as funding events, media, exhibitions and education projects.

There is no indication yet of how much money they will have to do that.

Irish language and Ulster Scots commissioners

There will then be two further commissioners - an Irish language commissioner and a commissioner "to enhance and develop the language, arts and literature associated with the Ulster Scots / Ulster British tradition in Northern Ireland".

They will also be part of the Office of Identity and Cultural Expression and will also be appointed by the First and Deputy First Ministers.

Interestingly, they can refer "issues of a challenging nature" to the director of the Office of Identity and Cultural Expression.

NDNA does not define what those issues might be though.

The Irish language commissioner's main role is to advise and set standards for public bodies on how they use Irish, and investigate complaints when those bodies fall short of services to Irish speakers.

However, any recommendations the commissioner makes have to be approved by the first and deputy first minister.

For instance, if they recommended that all motorway signs should be in English and Irish the First and Deputy First Minister would both have to agree.

That has led some Irish language speakers fearing they could face "a battle a day" to get services in the language.

Births, deaths and marriages

Marriages will be allowed to be registered in Irish

NDNA also commits to the repeal of an act dating from 1737, which bans the use of Irish in courts.

That will enable Irish to be used in court, and births, deaths and marriages to be registered in Irish.

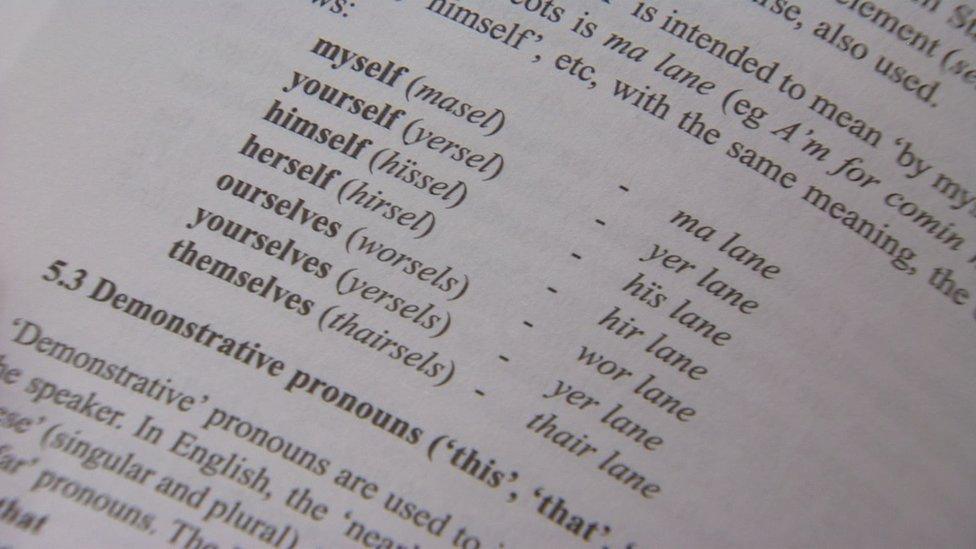

The role of the commissioner to enhance "the Ulster Scots / Ulster British tradition" is a little different to their Irish language counterpart.

While they too will provide advice and guidance to public bodies on services in Ulster-Scots - and investigate complaints - they do not set "best practice standards" for public bodies in the way the Irish commissioner does.

Their remit also includes "education, research, media, cultural activities and facilities and tourism initiatives" but no detail is given in NDNA on what their role is in these areas.

Policy on bilingual street signs has nothing to do with the NDNA agreement

However, NDNA makes clear that there will be no employment quotas for speakers of any language.

That means a public body does not have to commit to having a certain percentage of employees as Irish or Ulster-Scots speakers.

There are also some language measures already in existence which are nothing to do with the NDNA agreement.

Bilingual street signs are perhaps the most visible.

Policy on those is already the responsibility of Northern Ireland's eleven councils.