Tynan groats: Antique coins found in woods donated to Armagh Robinson Library

- Published

One of the Henry VI-era silver groats which have been donated to the Armagh Robinson Library

A collection of antique coins which date back almost 600 years has been donated to a County Armagh library due to their unusual link to the area.

The silver groats were minted in the 15th Century, during the reign of Henry VI which began in 1422.

They were found by a metal detectorist just over a decade ago in woodland near Tynan in County Armagh.

The coins were subsequently bought by a private collector, who has now donated them to the Armagh Robinson Library.

Although Henry VI groats are not particularly rare, it is the location and condition they were found in that makes them historically significant, according to currency expert Nic Wright.

Beyond the Pale

Unearthing this particular type of British coin in rural woodland in County Armagh - so far from the seat of English power in medieval Ireland - is unexpected, he told BBC News NI.

Mr Wright is a member of the Numismatic Society of Ireland, an organisation dedicated to the study of currency, and he has been researching the Tynan coins for some time.

The groat- a fourpence coin - was the most common coin produced during Henry VI's reign, he explains.

The Tynan groats were found intact and had not been "clipped" or devalued

He estimates there are "thousands" of Henry VI groats in public and private collections.

But what is unusual about the Tynan groats is that they were found still intact, in a part of Ireland far outside the area known as the Pale.

"In this period, English control of Ireland really was centred on Dublin and Carrickfergus, and not much further west than that," says Mr Wright.

"And where English, Scottish and continental coins show up in Ireland in this period, most of them have been clipped - they have the outside ring of text removed which reduces the weight of the coin."

The practice of clipping coins devalued the currency and prevented the money being spent outside Ireland.

So how much money are we talking about?

Together, the six groats found in Tynan equated to 24 medieval pence - not exactly a fortune but still a reasonable sum of cash in the 15th Century.

"The daily wage of a skilled longbowman at the time was between four and six pence per day," says Mr Wright.

"I know if I lost my weekly wage while walking through a wood, I'd be rather annoyed."

The exact location of the find is still unclear, so we can only wonder if they were accidently dropped or intentionally buried for safekeeping.

'Historical curiosity'

Mr Wright says his "best guess" is that the coins belonged to someone who had travelled from England or the continent to visit either Tynan or the nearby Armagh city, as both locations were important religious sites.

According to the Annals of Ulster - a medieval chronicle of Irish history - Tynan was home to a religious settlement as early as the year 1072.

Armagh city, meanwhile, is the ecclesiastical capital of the island of Ireland.

Armagh city is used as the base for both the Church of Ireland and the Catholic Church in Ireland (aerial photo circa 1951)

As regards current valuations, Henry VI-era groats can sell for between £100 and £300 each, depending on the quality of the coins, according to Mr Wright.

"They are not particularly valuable in and of themselves, but valuable for their historical curiosity," he added,

Buried treasure?

The Tynan groats were discovered by a metal detectorist from eastern Europe, who sold them at auction in 2010.

"The person who found them confirmed that they had all come from a piece of woodland, and that he'd visited the piece of woodland multiple times but hadn't found any more," says Mr Wright.

There are strict rules governing metal detection in Northern Ireland, external and in many circumstances, the discovery of archaeological objects must be reported to the authorities under the Treasure Act.

However, single coins found on their own are not considered to be treasure, and the same exception can apply to "groups of coins lost one-by-one over a period of time," according to government guidance.

The groats were bought by private collector Alan Dunlop, who sought advice on whether or not they fell under the terms of the Treasure Act.

Private collector Alan Dunlop, who bought the coins at auction in 2010, presented them to the library's director Robert Whan

"We have spoken to the Ulster Museum, who are the the authority that you're supposed to contact for this material," Mr Wright said.

"We have explained the context of how they were found, that the intention of the person who bought them was to study them and then donate them to the Armagh Robinson Museum, and so it was decided that there was no obvious cause to pursue it under the Treasure Act."

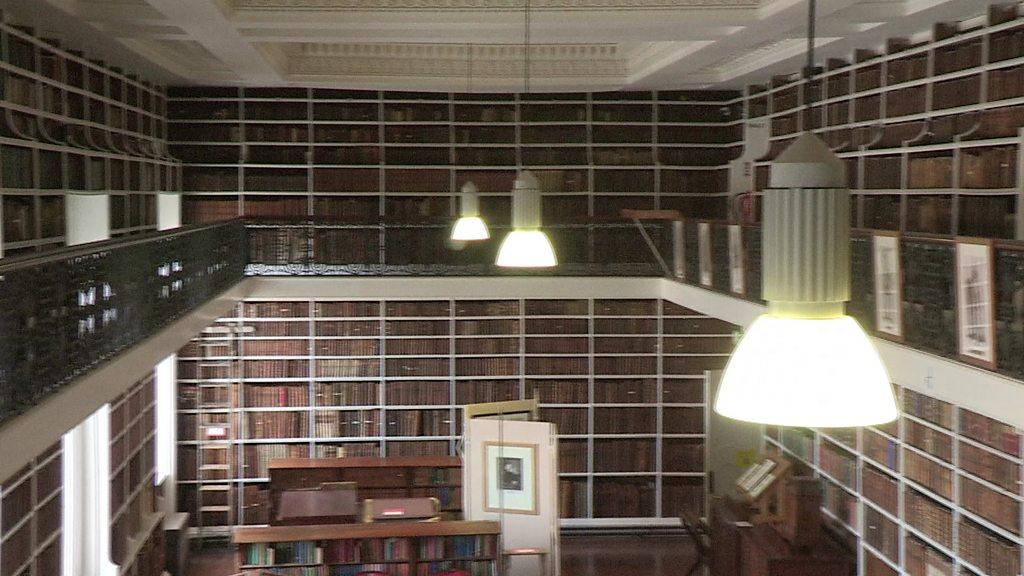

The Armagh Robinson Library and museum is the oldest public library in Northern Ireland.

It was founded in 1771 by the Church of Ireland's most senior cleric, Archbishop Richard Robinson.

Grand ambitions

The wealthy Yorkshireman held the dual titles of Anglican archbishop of Armagh and primate of All Ireland from 1765 until his death in 1794.

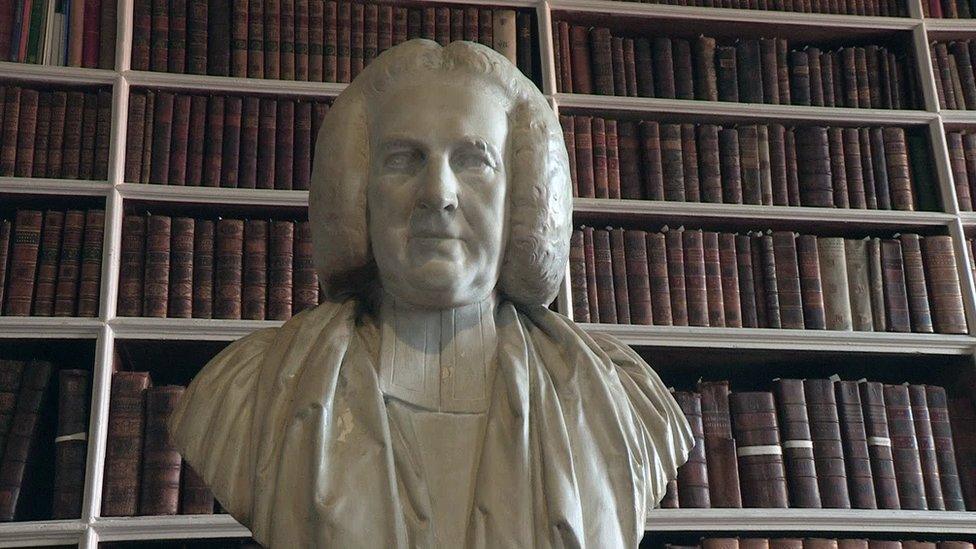

A bust of Archbishop Richard Robinson stands in the 250-year-old library which bears his name

Archbishop Robinson had grand ambitions for Armagh and is largely credited with transforming the rural market town into a Georgian city.

The library, the Bishop's Palace and the Armagh Observatory are among the buildings he commissioned, as part of his unfulfilled aspiration to establish a university in Armagh.

The archbishop also had a keen interest in numismatics and was an enthusiastic coin collector himself, according to the library's director, Robert Whan.

His legacy means the building on Abbey Street is now home to one of Northern Ireland's biggest antique coin collections.

The Armagh Robinson Library is marking its 250th anniversary this year and is hosting an exhibition on silver and gold, external as part of its celebrations.

The artefacts on public display will include a Tynan groat when the exhibition is formally launched on Tuesday 29 June.

- Published17 April 2021

- Published14 October 2019