NI 100: Life as an MP in the Northern Ireland Parliament

- Published

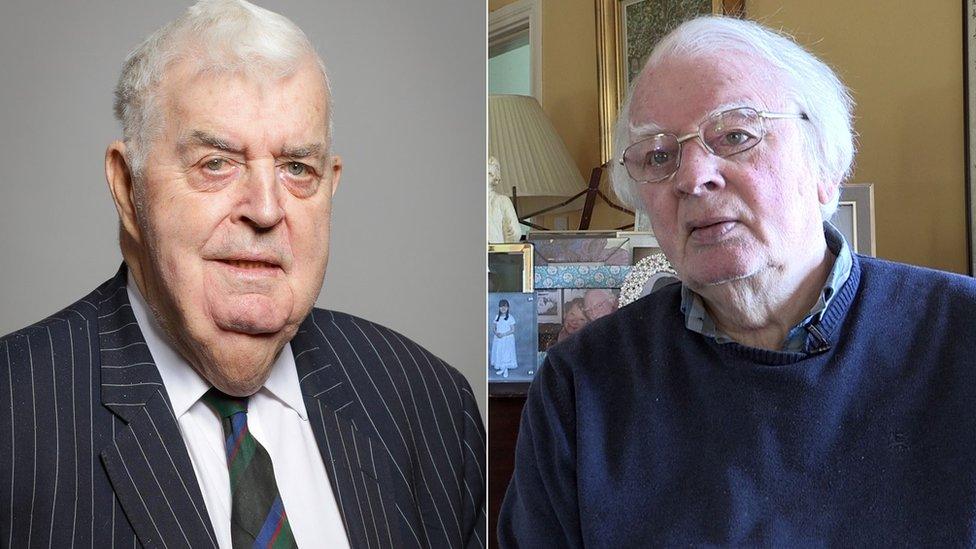

Lord Kilclooney and Austin Currie were elected to the NI Parliament in the mid-1960s

A century after the Northern Ireland Parliament was established - and 49 years since it was abolished - there are only a handful of people still alive who served as MPs.

Two of them are Lord Kilclooney - known as John Taylor when he was an MP - and Austin Currie.

Both were in their 20s when they were elected for neighbouring constituencies one year apart and both have had long political careers that have taken in many of the most significant developments in Irish and British politics over the course of almost 60 years.

One a nationalist and one a unionist, their experiences of the old parliament were distinctly different, although both remember at least one occasion when ordinary constituency work united them in a common cause.

Mr Currie was just 24 when he won a by-election for East Tyrone as a Nationalist Party candidate in 1964, one of nine MPs from the party in a parliament where the Ulster Unionist Party held 34 out of 52 seats.

He says the Stormont he arrived at to take his seat was "a very alien place".

"Looking at it you could see not one Union Jack flying but two and when you came through the door you saw [former Unionist leader Lord] Craigavon's statue there on the stairs and all around the place it was totally unionist, no sign of any nationalists anywhere," he says.

"It was absolutely a cold house for Catholics not only then, it had been from the very beginning, and then of course Stormont was created for the purpose of having unionist domination."

Austin Currie (second from right) was an early member of the SDLP along with (l-r) Ivan Cooper, John Hume, Paddy Devlin and Paddy O'Hanlon

A year later in neighbouring South Tyrone, John Taylor was elected as an Ulster Unionist at the age of 27, and believes his selection by the party was helped by a desire to have a young unionist as a counterpoint to Mr Currie.

He recalls entering a parliament where there were many towering unionist figures - the former prime minister Lord Brookeborough among them.

Was Stormont in his view, as in Mr Currie's, a cold house for nationalists?

"Well of course prior to 1965 the Nationalist Party boycotted it," he says.

"It was only after that that they accepted the role of official opposition, so they made it a cold house for themselves, people seem to ignore that.

"But once Eddie McAteer became leader of the opposition they played a very major role in the operation of parliamentary procedure, so they played a very full part".

John Taylor pictured after winning a seat in the European Parliament in 1979

He also remembers fondly his time working with Prime Minister James Chichester-Clark and is the last surviving member of the Privy Council of Northern Ireland.

But his first focus when he was elected, he says, was on constituency work, rather than parliamentary procedure.

"One of the big controversial issues, and one that Austin Currie and I worked very closely together on, was the extension of the M1," he says.

"The plan was that the M1 would stop short of Dungannon and have all the traffic going through Dungannon in what was called a through-pass.

"Currie and I joined together in a campaign against this through-pass, which would have been horrendous for Dungannon and in the end [the department] caved in and we got the bypass which went right through to Ballygawley.

"Austin and I, although he was a very strong nationalist and I was a very strong unionist, we could work very closely together and did on issues of local interest because Dungannon was 50% unionist and 50% nationalist."

So in a parliament with consistent unionist majorities and where nationalist politicians were excluded from government for its entire history, was this cooperation unusual?

Lord Kilclooney thinks not, and in fact believes personal relationships were better than they are in the modern Northern Ireland Assembly.

"I don't think you'd hear of a Sinn Féin member meeting a DUP member privately in a coffee shop and arranging a campaign, which Austin Currie and I did," he says.

The statue of Lord Craigavon still stands in the Great Hall at Stormont

Mr Currie, on the other hand, recalls "not having too many conversations with unionists" when he was elected, although he too remembers working closely on the local issue of the M1 extension.

"John Taylor and I had known each other and been active politically at Queen's [University] and we did have one common interest, which was the extension of the motorway," he says.

"We cooperated very closely in that respect, but after a certain period of time, particularly when I very strongly brought up cases of discrimination in housing, the cooperation didn't continue."

Stormont was, in his view, an institution destined to fail.

"The old parliament had a purpose which was permanent control of unionism in that part of Ireland and if the unionists had treated fairly the nationalist community then it could be possible that some nationalists might eventually support Northern Ireland, particularly as the social welfare state and the education system arrived," he says.

"But, and despite the advice of Lord Carson, the unionist leadership decided that they were going to have a Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People and from the beginning there was no chance of the nationalist catholic community having any support for the Stormont Parliament."

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

Year '21: You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created a hundred years ago by listening to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch-up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published20 June 2021

- Published6 June 2021

- Published13 June 2021