Brendan Adam's daughter Angeline says hearing his voice 'priceless'

- Published

'I never got to know him, now I can hear his voice'

In 1968, languages curator Brendan Adams spoke to school children in County Armagh as part of a study into dialect and accents.

His recordings resurfaced last week on a BBC News NI report about an Ulster Folk Museum programme called Unlocking our Sound Heritage, which has digitised Mr Adams' tapes.

But it was the sound of Mr Adams' voice on those recordings that caught the attention of Angeline Adams - because he was the father she had never met.

Mr Adams died in 1981 when he was 62 years old, just two days before his only child, Angeline, was born.

"He passed away two days before I was born, so I never got to know him except through people's stories and through his papers, and now being able to hear his voice," she says.

"A friend messaged me on Friday afternoon with a link to the article on the BBC website and said: 'Is this who I think it is?'

"I clicked through and heard the little snippet of audio that was on Good Morning Ulster."

Ms Adams had only ever heard a short recording, in poor quality, of her late father's voice.

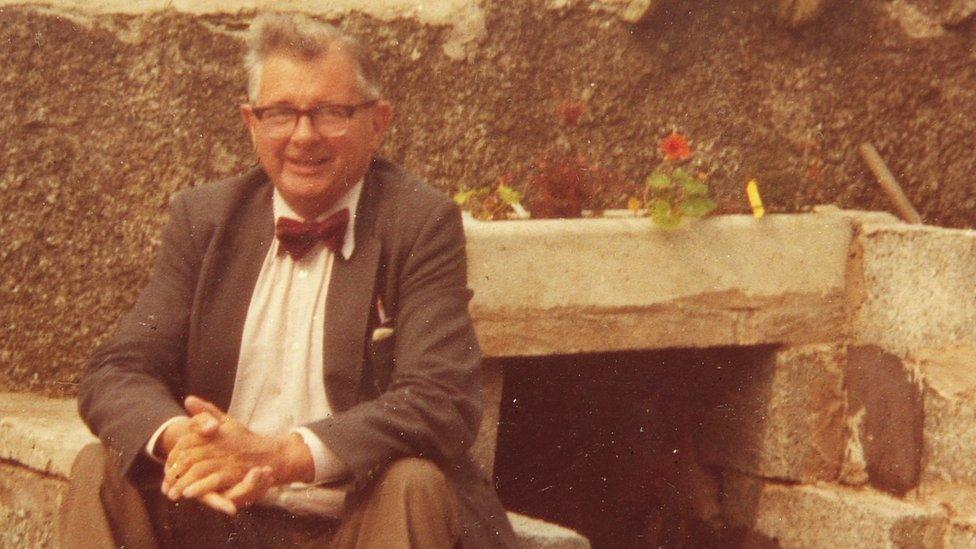

Brendan Adams died just two days before his only child, Angeline, was born

She has spent the past few days listening to the lengthy recordings sent to her by the museum.

"This is something I can turn to, I actually can sit down and hear his voice. I can actually get to recognise his voice," she says.

"It's always been strange that so many people know him very well and I'm the only person who doesn't and, at the same time, I'm the last living person to whom he will really matter on a personal level, so that really is extraordinary to me."

So what do these recordings mean to Ms Adams and her family?

"Absolutely priceless, I mean there really are no words," she says.

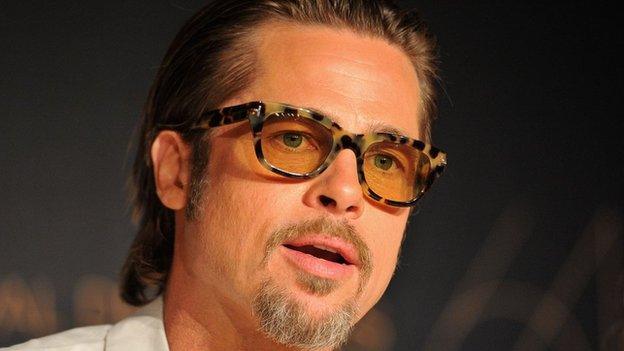

Angeline Adams had only ever heard a short recording, in poor quality, of her late father's voice

"Of course it was a big surprise and I've been going through his personal papers and he's been on my mind a lot recently.

"In October it will be the 40th anniversary of his death, so it feels like a fitting time for me to finally hear this.

"It's a link to him I didn't expect to get."

Ms Adams, an author, says she's proud of her father's work in languages.

"Many old colleagues have told me how passionate my father was about his work," she says.

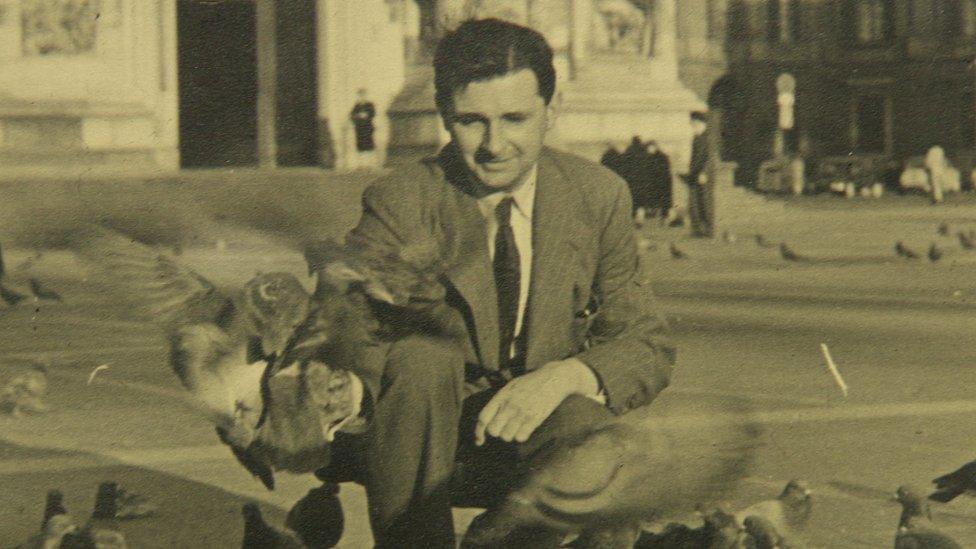

Angeline says she can now get a sense of the man her father was

"I find it so powerful, because, so often in Northern Ireland, language and culture and identity have become battlegrounds, but dad really believed that the way we speak and our languages, our culture, all of that was for everyone.

"I can now get a sense of the man he was, and what he was like when he was doing what he loved the most.

"I wish I had met him."

Related topics

- Published11 November 2020

- Published12 September 2016