Mary Ann McCracken letters shed new light on last years

- Published

Mary Ann McCracken wrote of collecting for charities into her 10th decade

Anti-slavery activist Mary Ann McCracken went door-to-door collecting for charity into her 10th decade, a cache of previously unpublished letters has revealed.

The 19th Century abolitionist is often said to have pamphleteered at Belfast docks into her 89th year.

But records show her to have been collecting for Belfast's poor and campaigning for the anti-slavery cause for several years more.

Northern Ireland-born researcher Dr Cathryn McWilliams has catalogued six-and-a-half decades of Mary Ann McCracken's correspondence.

Recently there has been a renewed push to bring the abolitionist out of her beloved brother's shadow, with the launch of a foundation in her name.

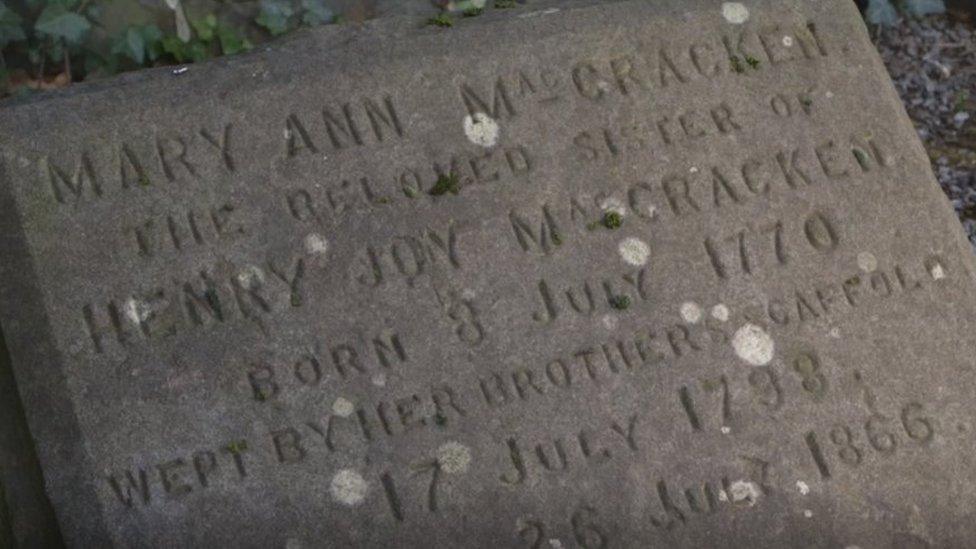

Her brother Henry Joy McCracken was hanged in Cornmarket in Belfast in 1798 for his role in the failed United Irishmen rebellion against British rule.

Mary Ann McCracken is represented in murals and public art in Belfast and Londonderry

A statue of Mary Ann McCracken, along with fellow nationalist activist Winifred Carney, is planned for Belfast City Hall.

Dr McWilliams said the 181 letters, including some never before published, gave "a new level of detail and more accurate picture" of Mary Ann McCracken's life and character.

'Never still'

In a letter dated 1861, at age 90, she wrote she collected for charities "on fine days" and had a "brilliant hope" of an end to slavery in the United States.

Committee minutes for the Belfast Ladies' Industrial National School for Girls record her collecting for them as late as 1863.

Dr McWilliams also found records of the Belfast streets where she went door-to-door, accompanied by her grandniece Anna McCleery.

"She's always moving, I think that's something that really sticks out, is that she is constantly doing something. She's never still," Dr McWilliams said.

"She was just a constant figure on the streets of Belfast, everybody must have known her."

Dr Cathryn McWiliams gathered 181 letters

Dr McWilliams first learned about Mary Ann McCracken in an Irish history exhibit that referred to her accompanying her brother Henry Joy to the gallows, external.

"I thought: 'Hang on a minute, is this all she gets - two paragraphs? I need to learn more'," Dr McWilliams said.

Mary Ann McCracken was born in Belfast in 1770 and died in 1866, seven months after the end of the American Civil War, which brought about the end of slavery in the US.

In a previously unpublished 1861 letter to fellow abolitionist and United Irishmen historian Dr Richard Madden, Mary Ann McCracken said she was "entirely free from bodily pain" and in better health than she had been in many years.

She wrote: "'Tho my sight and hearing are greatly impaired and I stoop much and lean to the one side but am still able to go out on a fine day and collect.

"All which gives an unspeakable charm to life, and now I have the brilliant hope of the approaching abolition of slavery."

'Love of filthy lucre'

Four years after she wrote that, on 6 December 1865, the US ratified the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the country.

Mary Ann McCracken was on the committee for the Belfast Ladies' Anti Slavery Association from its establishment in 1846, and in 1859 lamented to Dr Madden: "Belfast once so celebrated for its love of liberty is now so sunk in the love of filthy lucre."

She said there were fewer than 20 women anti-slavery advocates "paying 2/6 yearly...and none to distribute papers to American Emigrants but an old woman within 17 days of 89".

At 87 she still made handicrafts to be sold at anti-slavery fairs in Philadelphia and Boston.

There is a renewed push to bring Mary Ann out of her brother's shadow

Mary Ann McCracken worked to preserve the memory of the United Irishmen into her 90s and helped Dr Madden write their history, Dr McWilliams said.

The Society of United Irishmen, was founded in 1791 in the wake of the French Revolution.

With members from Ireland's various Christian denominations it sought constitutional reform but after being frustrated in its efforts eventually launched a rebellion against British rule in 1798.

In 1859, Mary Ann McCracken wrote about the death of, Thomas Russell, one of the founding members of the United Irishmen, and her struggle to collect from his Belfast friends to care for his "desolate sister", writing: "Such indifference is painful to contemplate and not creditable to human nature."

Dr McWilliams said: "She was until her final decade writing letters with Madden, trying to keep the memory of the United Irishmen and their goals alive and that she saw her work as continuing their good work, to have equality.

"She has very much a strong moral compass and it drives her the whole way through her life.

"Especially in Northern Ireland someone like that needs to be held up."

Momentous to the mundane

Her letters move from politics, to history, and every-day life in 19th Century Belfast.

Aged 84, she told Dr Madden she had been ordered to bed because of "overexertion", although she had felt well but had been "obliged to submit rather than add to my niece's anxiety", felt "inwardly" well, and said the illness stemmed from a cough she had had from age six.

Mary Ann McCracken was likely a "constant figure" in Belfast

Norma Sinte, chairwoman of the Mary Ann McCracken Foundation, said Dr McWilliams' research was "invaluable".

"Every piece of correspondence allows us greater insight into the kind of person she was, the challenges she faced and at times the frustrations she felt," she said.

"We are delighted that Dr McWilliams has dedicated years to her research to Mary Ann McCracken, reflecting her obvious admiration for her."

For Dr McWilliams, it has been a seven-year project to expand on that brief exhibit reference.

She recently completed her PhD at Åbo Akademi University, Finland.

"It's funny that two paragraphs in the Ulster Museum have led to 1,000 pages," she said.

- Published2 June 2021

- Published23 January 2021