Holy Cross: Remembering a school run like no other

- Published

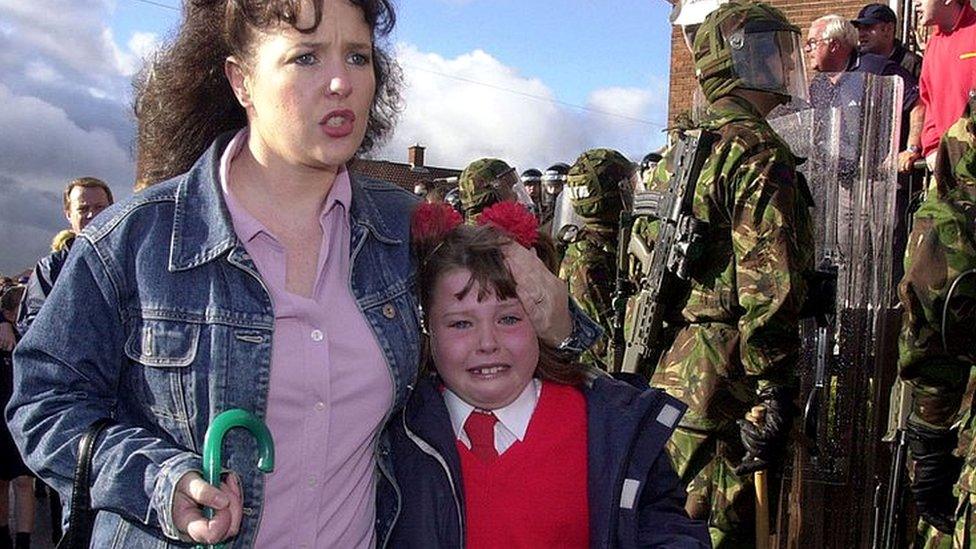

Police officers in riot gear escorted schoolgirls and their families past the protesters in 2001

Twenty years ago, a violent sectarian dispute took place outside Holy Cross Primary School in north Belfast.

The school was thrust into the international spotlight, when hundreds of loyalist protesters tried to block the route taken by the school's pupils and their parents, who were from a Catholic background, on their walk to class.

BBC News NI's Gareth Gordon, who was among the reporters who covered the story at the time, shares his memories.

Have tape recorder, will travel. Once, my journey was a road trip to the places left behind when Northern Ireland got peace.

There I met mostly good people trapped by location and a history they didn't write. But some not so good as well.

Drumcree, Ormeau Road, Cluan Place, Short Strand, Whitewell, Ardoyne and Holy Cross.

Of all of them, Holy Cross is the name I most remember, with very good reason.

Catholic Ardoyne is beside Protestant Glenbryn. Just another interface but with one big difference.

Tucked away at the Glenbryn end of the Ardoyne Road is the Catholic Holy Cross Girls' Primary School.

And for a time in 2001, before an even more grave event in New York replaced it in the world's collective consciousness, it made headlines around the globe.

Here's why.

A large police convoy waited to protect the Holy Cross school run in 2001

No community living on either side of Belfast's many peace walls had a monopoly on grievance, and that summer there was a lot of it about.

Attacks from one side on the other went both ways and Ardoyne saw more than its fair share.

Twenty years on, the blame game has been well played out elsewhere.

What follows here are my memories of a situation I, or no-one else who witnessed it, will ever forget.

At its heart are the innocents who attended Holy Cross Girls' School.

Children held hands tightly with family members as they passed police and Army lines

Locals claimed some Protestants were attacked while putting up flags in late June just before the end of summer term.

There was a claim one of them was knocked off a ladder. As usual this is disputed.

But what's not disputed is that the school was then singled out for attention by loyalist protesters - a situation that remained unresolved all summer until the new term began in September.

Everyone remembers the girls, some crying, being taken to school by parents with police shielding them from angry people shouting insults from the "other side".

Whatever the rights and wrongs of the cause which began this form of protest, it was lost in the terrified faces of the girls forced to suffer a school run like no other.

The daily school run became a traumatic experience for children

The Wednesday morning was the worst. A pipe bomb was thrown, probably aimed at police, but the explosion was loud enough to send children into hysterics.

Later I asked two Protestant women why it had happened. This is how it went.

Woman one: "There must be a reason why we're doing this. There must be. We've had enough fear and we can't take it no more. We don't care."

Woman two: "We don't care; we're like the Jews now, I think."

Woman one: "I mean I wouldn't let my son or my daughter come home from a disco or anything from that Crumlin Road to get in here and it's the only way they can come at night."

Me: "This morning, whatever the wrongs and rights here, a bomb went off close to the children going to school. How did that make you feel?"

Woman one: "I'm past feeling. You can't understand that. I am past feeling. I'm not going to run my ones down for throwing that bomb."

Me: "But you're not a terrorist."

Woman one: "I'm not. No, I'm not a terrorist. No, I'm a mother. I'm a mother of five children."

Me: "Who's to blame for this?"

Woman one: "Themmuns down there."

Me: "How would you have felt this morning if a child had been killed?"

Woman one: "I'd have felt terrible. I'm a mother of five. Yes, it would be like me losing one of my own. I could feel for that mother."

Me: "So you're not past caring."

RUC officers shielding an injured colleague during the 2001 Holy Cross dispute

The next morning the walk to school was played out on live television and radio to a world which could not quite believe what was happening.

My job was to relay this live on BBC Radio Ulster's Good Morning Ulster programme which remained on air way past its scheduled end time of 09:00 BST.

I did so against the ear-splitting sound of protesters blowing whistles. But, thankfully, there were no more pipe bombs and the children made it through.

Police in riot gear protected families from attack on the school run

I had no idea if I was speaking to thousands or to myself until we reached the school and the presenter Seamus McKee was able to ask me a question.

One woman later told me she missed an important appointment because she couldn't leave her car listening to me until it was clear the children had made it through unscathed.

After that, the protest seemed to peter out. No-one had the stomach for any more of this madness.

The following week I stood at the school gate as two clerics who had been centrally involved in trying to resolve things - Father Aidan Troy and the Reverend Norman Hamilton - emerged after a joint school visit.

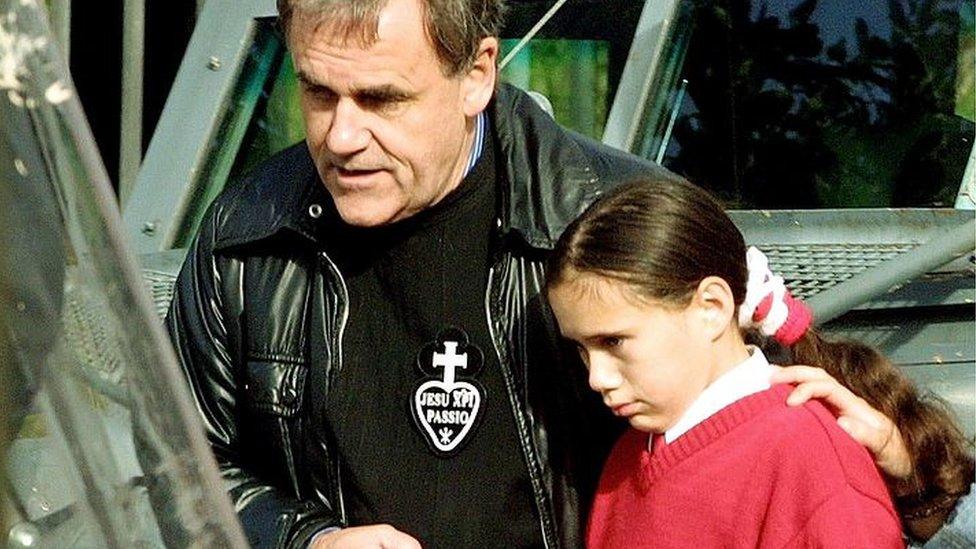

Catholic priest Fr Aidan Troy helped shield schoolgirls on their walk to school

I returned to the BBC happy the protest was now over and looked forward to an easy day.

That day was 11 September 2001 and my report of the school visit never made air.

Days later I arrived in New York to cover the aftermath of the attacks on the Twin Towers.

We went first to Battery Park, a residential area near the World Trade Center, where people unable to return home watched lorry after lorry carry away the rubble of their lives.

"Are you really from BBC Northern Ireland?" asked a woman who told me she and her daughter had spent the evening before the attack crying at the scenes of those young girls being escorted to school in Belfast.

Even in the midst of a horrific terrorist attack on the other side of the Atlantic, there was no escaping Holy Cross.

Related topics

- Published1 September 2016

- Published3 September 2011

.jpg)