Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis on rise in Northern Ireland

- Published

As many as 300 people in NI are diagnosed with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) every year

About 1,200 people are living with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) in Northern Ireland.

But not everyone who is diagnosed can get access to the same support and treatment.

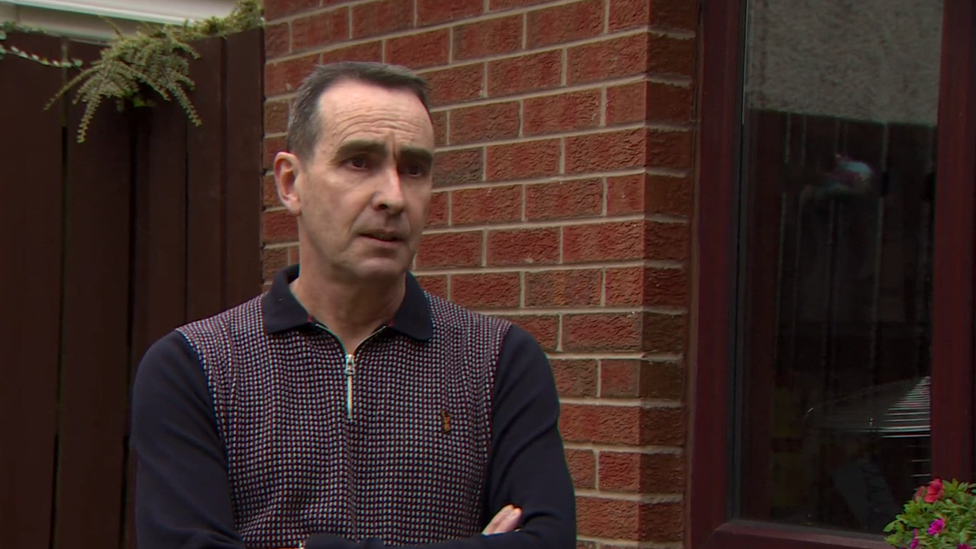

Jim Balmer has a competitive streak.

Bagpiping competitions were where he first met his wife. And when he moved on from piping, he took up squash and played for Ulster.

Now, his lungs don't work.

"Two years ago, I started feeling a bit breathless walking up hills, slight cough - persistent cough actually - very dry," the 52-year-old father-of-two recalled.

"And in showers, I would have coughed with the steam."

Jim Balmer says it was a "complete life change" when he was diagnosed with IPF

He went to his GP and was sent for an x-ray. Initially, shadows on his lungs were treated as pneumonia.

But when a follow-up x-ray showed no improvement, a CT scan was ordered, which the pandemic delayed until July 2020.

He was diagnosed with IPF, a condition that causes scarring of the lungs and has no cure.

"Complete life change," Mr Balmer said.

"Not only for me, but for my wife, my sons. I can't really do anything, go anywhere.

"I had to sell my company last week, I've worked for myself for 21 years and I can't do anything."

A growing problem

On top of the roughly 1,200 people who live with the condition in Northern Ireland, as many as 300 more are diagnosed every year.

"Data over the past 20 years shows that more and more people appear to be developing fibrosis in the lungs," said Northern Trust respiratory consultant Dr Eoin Murtagh.

"It is important that we now change the type of health service we provide, to make sure patients have access to the services they need for early diagnosis and an accurate diagnosis, and then availability for appropriate treatment."

Dr Eoin Murtagh says he would like to see "co-ordinated, dedicated services" available to patients across NI

According to a British Lung Foundation report in 2016, Northern Ireland has the highest prevalence of IPF of any region in the UK.

But after diagnosis, not everyone here can get access to the same support and treatment, according to Dr. Murtagh.

"There's great variability depending on where you live, which trust you're in, as to which services you may have access to and the waiting time to avail of assessment and investigations," he said.

"So we would like to see co-ordinated, dedicated services available to patients across Northern Ireland."

Currently, only the Northern Trust has a dedicated multi-disciplinary lung disease team with five consultant and nursing staff.

Belfast Trust says it has a consultant and a specialist nurse, the Western Trust has a dedicated pulmonary fibrosis nurse, and the South Eastern has a nurse specialist and a part-consultant who lead their unit.

"The 'idio' is 'idiot'"

Anti-fibrotic drugs can prolong and improve the quality of life for sufferers. In Europe, the US, Canada and New Zealand, they are prescribed on diagnosis.

But current guidance in the UK says they should only be prescribed when a patient's lung function is within a certain range and they may be stopped if lung function drops below that range.

The guidance is currently under review.

Jim Balmer says more funding and research into what causes the condition is needed

"Although they don't cure the condition, we know that they slow down the progression of the disease," said Dr. Murtagh.

"On average, they extend life by an additional three years for patients who are on those medications.

"So if we identify patients earlier in the course of their illness, we could have a bigger impact with that medication."

Jim Balmer got information and help from the Northern Trust Pulmonary Fibrosis Support Group, external.

His hope is that awareness of the condition is raised and that sufferers in Northern Ireland can get help, regardless of where they live.

"More funding, more research into what causes it [is needed]," Mr Balmer said.

"Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis - the 'idio' is 'idiot'. They don't know.

"They don't know what causes it."

Related topics

- Published22 September 2021