Northern Ireland's changing faces and places four decades apart

- Published

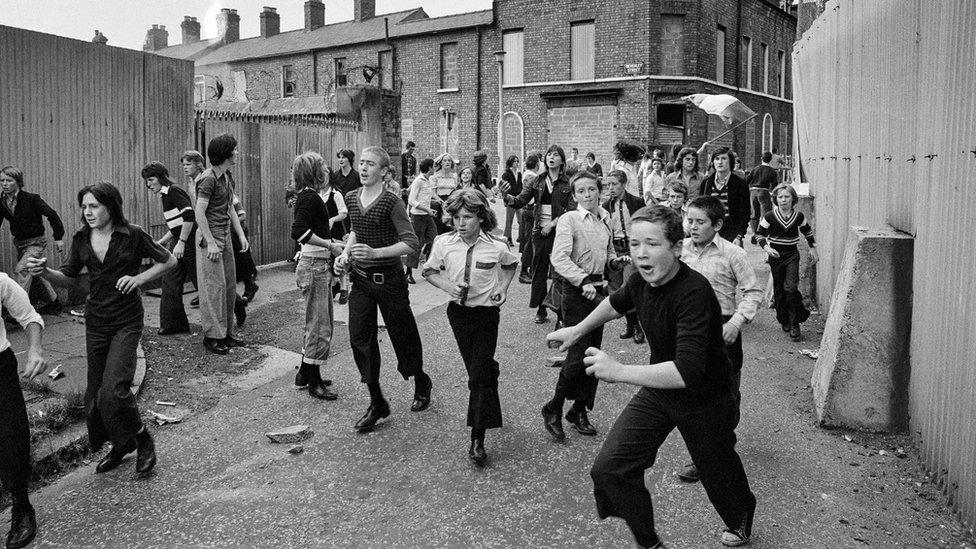

Beverly Street, west Belfast, August 1975

"It was real. It had spontaneity. People reacted quickly to the world around them."

Northern Ireland in the mid-1970s would not have been at the top of many travel destination lists, but a young French photojournalist, inspired by his peers, was drawn to the place.

During the summers of 1975 and 1976, Bernard Lesaing travelled to Londonderry and Belfast taking photographs on the streets of Northern Ireland's two cities.

The Troubles were less than a decade old and Bernard was at the beginning of his career.

During an earlier trip to the Republic of Ireland, he hadn't travelled north of the border.

Lower Falls Road area, west Belfast, August 1975

"The representation of the time was quite dark, of course, but there were some quite famous French photographers who took pictures of Northern Ireland, including Gilles Peress," he said.

"So that was a big influence and I thought I'd go back and try and see for myself."

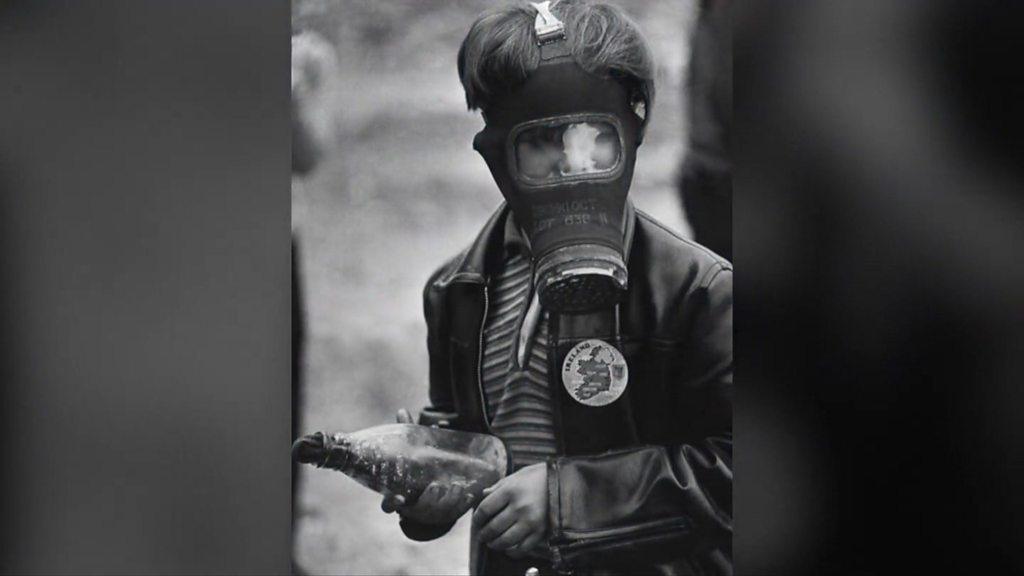

Apprentice Boys parade, Derry, 12 August 1975

What he saw was the obvious conflict, the tension between communities, but also the activism of people striving for change.

In August 1976, Bernard was in Belfast as three young children were tragically killed.

On 10 August, Anne Maguire was walking along Finaghy Road North with her three children when an out-of-control car plunged into them.

The car's driver, an IRA man, had been fatally wounded by an Army patrol that was chasing him.

Within three days, the Peace People group was born.

They marched in cities and towns such as Belfast, Enniskillen and Ballymena and held one of their most high profile rallies in Trafalgar Square in London.

Peace march, Belfast, August 1976

"After the death of the Maguire children, suddenly the women just took over and decided to react," Bernard says.

"The general spontaneity of the 1970s that, you know, people reacted maybe a bit more quickly to things or thinking ahead or without thinking twice."

Bernard says he came to Northern Ireland to capture whatever he saw, but a lot of that was joy, the smiles on people's faces despite the Troubles surrounding them.

On the Shankill, west Belfast, August 1976

"Wherever there is conflict, of course there are moments of strong tension, but also moments when people have to relax a bit, forget about the conflict or think they're forgetting about the conflict.

"When I was 22 and first in Belfast and Derry, people were willing to talk. It was very easy for a young French photographer to engage with people."

These images. along with others taken on a return trip to Belfast 40 years later, became the basis for a book, and now an exhibit at the Ulster Museum.

Carlisle Circus, north Belfast, August 2019

But Bernard did not want his work to be a French person's vision of Northern Ireland. He wanted people to tell their stories, so his photographs are accompanied by personal testimonies.

Helping him to gather the testimonies was Karine Bigand, a French academic who has lived and worked in Northern Ireland.

"We wanted to include the people, give a voice to the people you know rather than us coming you know, for three weeks and saying: 'Hi, we can tell you all about it.'

"I lived in Belfast about 10 years ago and I worked with Healing Through Remembering and at that time, we had an exhibition going round, called Everyday Objects Transformed by the Conflict.

"They had borrowed objects linked to the conflict, but they had asked the owners to write the label for the object."

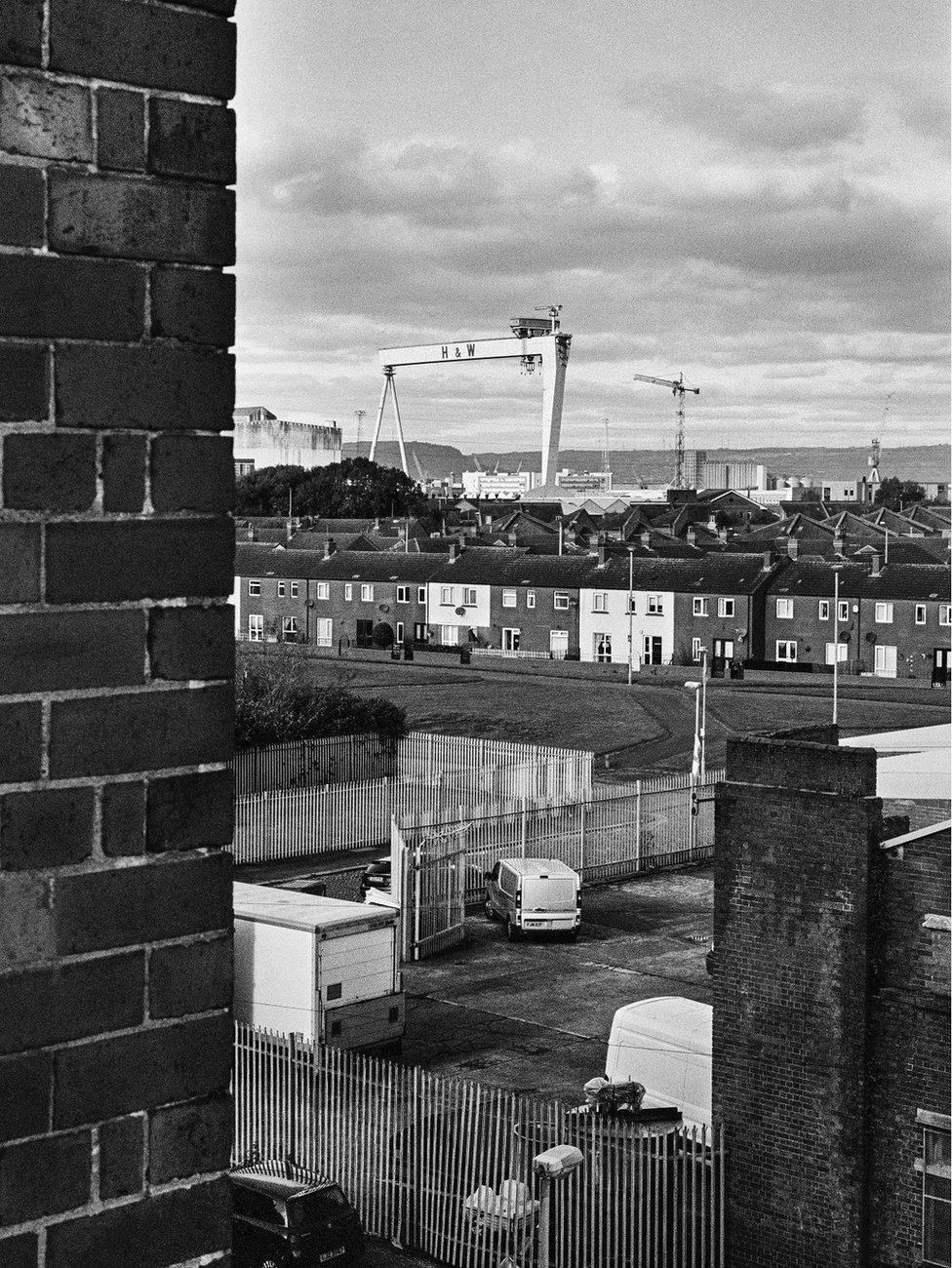

A view of the shipyard, east Belfast, October 2019

She added: "We wanted to do that with the people, to have them tell their own stories. Our deliberate choice was to focus on positivity and variety of people as well, from different backgrounds.

"The variety was important so that it was not caught in the orange and green, and the positivity and people who were involved in the community."

Karine says they have a good recollection of the past, and how much things have moved on.

"They want to move forward," she says.

"As Bernard says, it's really a lesson for us in France, about what living together means. There's this real kind of openminded approach to the place where they live, and to their neighbours and so on."

Musicians gathered for a session in the John Hewitt bar in Belfast in 2019

And what changes did Bernard see on the streets on returning after four decades?

"The landscape is different, buildings are different, and also the way people move around," said.

The city has even lost a little bit of what made it special for him.

"It [Belfast] looks like just another European city, you know, with the usual shops that you find in European cities, to the detriment in a way of independent shops," he added.

Belfast's changing image also brought his son to the city, now seen as fashionable tourist destination, a marked change from the "dark place" Bernard had heard about in the 1970s before he first came to Northern Ireland.

The Faces and Places exhibit is currently running at the Ulster Museum in Belfast, external.

Related topics

- Published22 November 2020

- Published15 August 2019