Child abuse: Stormont ministers set March date for apology

- Published

Child abuse survivors are still waiting on a state apology, five years after HIA inquiry

Northern Ireland's first and deputy first ministers will make an official apology to survivors of child abuse in institutions on 11 March, it has been confirmed.

The apology was recommended in the final report of the Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry (HIAI).

It was published five years ago.

Paul Givan and Michell O'Neill will make the apology in parliament buildings on behalf of the executive.

Officials will meet with survivors' groups over the coming weeks to discuss the event.

The inquiry examined the period 1922-1995, and found there had been widespread and systemic abuse at institutions.

The chair, the late Sir Anthony Hart, recommended compensation, an apology and a memorial.

Campaigner Margaret McGuckin said many of those who wanted an apology have now died

Margaret McGuckin, from the group Survivors and Victims of Institutional Abuse (SAVIA), said the announcement was "welcome" but had been a "very long time coming".

"I think it's happened because of the pressure we had to apply again," she said.

"It's unfortunate so many people who wanted an apology have gone to their graves blaming themselves and will never hear the words: 'It wasn't your fault, it was our fault.'"

Kate Walmsley, who was sexually abused between the ages of eight and 12 at an institution in Londonderry, said: "All I've wanted was for somebody to say sorry."

She explained how her experience had affected the rest of her life.

Kate Walmsley was sexually abused between the ages of eight and 12 at an institution in Londonderry

"I just never felt I belonged anywhere. I still am lonely and feel I'm not accepted, and totally ignored."

Kate said she felt "more traumatised" by having to push for Sir Anthony Hart's recommendations to be implemented.

Days after the Hart Report was published, the powersharing executive at Stormont collapsed - leaving Northern Ireland without a government for three years.

Campaigners asked the then Northern Ireland Secretary Julian Smith to pass legislation at Westminster to set up the compensation scheme recommended by Sir Anthony Hart.

The late Sir Anthony Hart recommended a compensation scheme

Mr Smith did so in November 2019.

The Stormont Executive was restored two months later.

A review is currently being carried out into the financial redress scheme.

It's understood Stormont officials have heard several different views from survivors about the value and timing of an apology.

Confirming the date for an official apology, First Minister Paul Givan said: "Victims and survivors of historical institutional abuse have our full support, and we are determined they will receive the acknowledgement, support, and redress they deserve.

"Our priority remains approaching an apology with care and sensitivity, and basing it upon the experience of victims and survivors."

Michelle O'Neill acknowledged there would be "many different views" on a public apology and said the date had been announced in advance so that survivors and their families could give input.

"While no apology will make up for the shameful failures, and the pain that victims and survivors have endured as a result, we owe it to them to acknowledge the harm they suffered."

She added: "The needs of victims and survivors are at the heart of this and we are working to ensure that we have the right support in place - before, during, and after the apology is made."

'Beaten until they screamed'

Survivors of the institutions in Northern Ireland travelled from Great Britain, Australia and other parts of the world to give evidence at the Hart Inquiry - which was the biggest investigation of its kind to be held in the UK at the time.

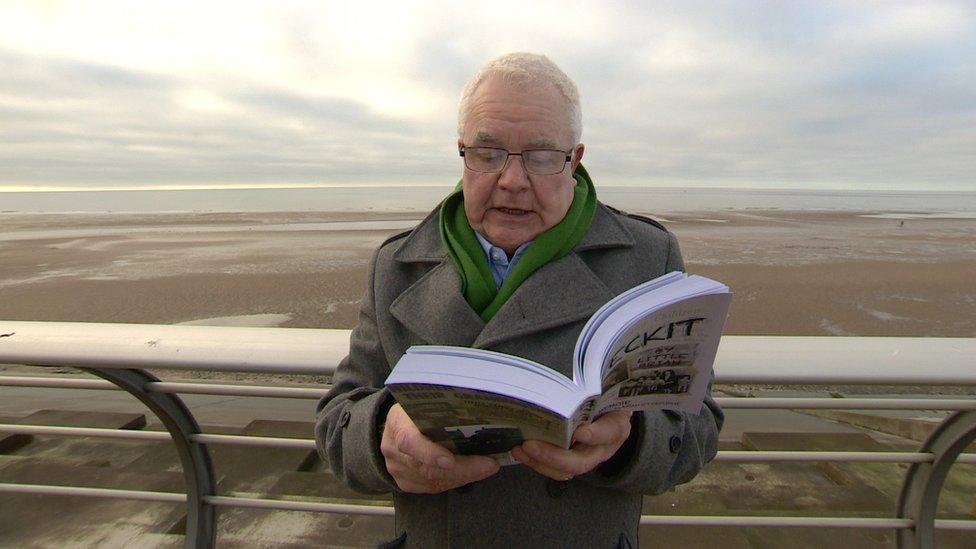

Brian O'Donoghue now lives in Lancashire.

When he talks about his childhood six decades ago - his pictures are sharp and his memories evidently vivid.

He describes having meals in a cellar at Rubane House, in County Down, as feeling "a bit like Oliver Twist to me".

Brian O'Donoghue recorded his experiences in a self-published memoir

His initial impressions of the institution, which was run by the De La Salle Brothers, was that it was "frightening", he didn't have good clothes to wear and he wasn't fed very well.

He was sexually abused and remembers how - at the age of nine - he "didn't understand what was happening, but I knew it was wrong to be touched".

In his self-published memoir - written from the perspective of his boyhood self - Brian recorded one incident where two boys who tried to run away were punished.

A partition between two classrooms was opened up, so everyone in the institution could be made to watch.

He said they were made to strip to a pair of swimming trunks, and beaten in front of all the other boys "until they jumped in the air and screamed".

"There was sweat pouring off the Brother who did the beating - that was how much he put into it."

'Should have come sooner"

Brian was born in Limerick and was first put into an institution in the Republic of Ireland, after his mother "went out for some milk of magnesia for the baby and didn't come back for two years".

After his time in Northern Ireland, he was also in a children's home in the north of England, which was "totally different".

"You weren't brutalised but any punishments were psychological - so you weren't spoken to, you were made an outcast," he said.

Looking back on his life, he described himself as becoming "fiercely independent" because "no-one's looked after me since I was a kid".

He has had depression for many years, and said his wife Marcia was "the first person in my life who gave me stability".

He said he maintained a positive attitude to life - "I get out there every day and make the best of it."

He is "grateful" to have received compensation through the Stormont scheme.

On the prospect of a state apology in Northern Ireland, he said: "Some people will say it should have come sooner - and it should have done.

"But that word - sorry - will make lots of people feel a bit better."

Related topics

- Published23 May 2020

- Published21 April 2021