Bloody Sunday victims remembered on 50th anniversary

- Published

Relatives of those killed on Bloody Sunday have been remembering their loved ones on the 50th anniversary.

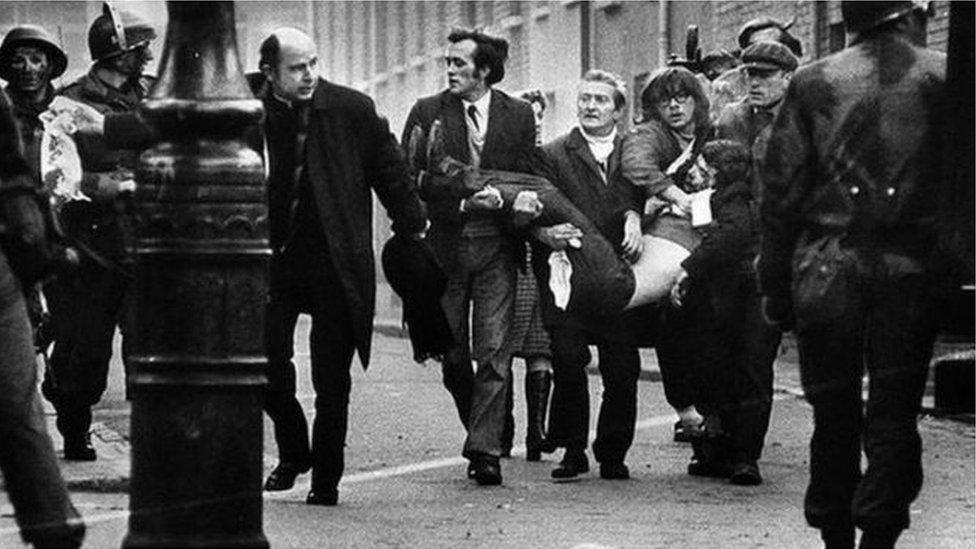

Thirteen people were shot dead when soldiers opened fire on civil rights demonstrators in Derry on 30 January 1972.

Taoiseach (Irish PM) Micheál Martin laid a wreath at a memorial ceremony in Londonderry and said he supported the families' campaign for justice.

The service was part of a series of events held in Derry on Sunday.

Mr Martin privately met relatives of those killed.

He said he had thanked the families for their "dignified, persistent and courageous" campaign in the pursuit of justice, truth and accountability.

"The families of victims should always have primacy in terms of policy considerations and in terms of dealing with the past," he said.

"I don't believe there should be amnesties for anybody, I believe the full process of the courts and justice should be deployed."

Mr Martin also said it would have been "helpful" if some of Northern Ireland's unionist political parties had been represented at the commemoration.

Irish President Michael D Higgins commended the people of Derry who have "led the way, in finding agreement and accommodation between communities and traditions".

In a recorded message during a special event at the city's Millennium Forum, the Irish president said the events of Bloody Sunday "reverberated across this island and around the world".

Wreaths were placed at the Bloody Sunday memorial during an event marking its 50th anniversary

"The 30th of January 1972 will live on in our collective memory, as will your efforts of vindication of the truth," he said.

The names of the 13 men killed, and of John Johnston, who was wounded on Bloody Sunday and died six months later, were read out during the event. Lord Savile said in his 2010 report into Bloody Sunday that Mr Johnston did not die from wounds he suffered on the day. His name is included on the official Bloody Sunday memorial.

The auditorium then fell silent at the precise moment the first shot was fired 50 years ago.

Earlier, relatives of those killed retraced the steps of the original march.

They also laid photographs of their loved ones at the memorial in Derry's Bogside.

Bloody Sunday brought worldwide attention to the escalating crisis in Northern Ireland, which came to be known as the Troubles.

Maisie McLaughlin's great grandfather Bernard McGuigan was among those killed on Bloody Sunday

Kay Duddy, whose 17-year-old brother Jackie was the first person to be shot on Bloody Sunday, said "it hurts as much 50 years on as it did at the time".

"We did not just lose a wee brother, we lost a whole generation. There's so many unanswered questions, would he have married? Would he have had a family?

"That is a very, very hard pill to swallow."

Irish Foreign Affairs Minister Simon Coveney, Sinn Féin president Mary Lou McDonald, SDLP leader and Foyle MP Colum Eastwood, and Alliance deputy leader Stephen Farry also attended the memorial service earlier.

Michael McKinney, brother of Bloody Sunday victim William McKinney, told the crowd the families are opposed to government proposals that would see an end to Troubles-related prosecutions.

"If they pursue their proposals, the Bloody Sunday families will be ready to meet them head on," he said.

"We will not go away and we will not be silenced."

Hundreds of people lined the streets of Derry

Presbyterian minister Dr David Latimer told the crowd the Bloody Sunday families have "tirelessly, across the decades, toiled to clear their loved ones' names".

He said their fight for justice has been inspirational across the world.

Archbishop Eamon Martin said the "horror inflicted on Derry" on Bloody Sunday has "thankfully been exposed and challenged".

The leader of the Catholic Church in Ireland was addressing a service in Derry's Saint Eugene's Cathedral.

"Very painfully the Bloody Sunday families were denied for too long the truth about what happened to their loved ones, and sadly they are not alone," he said.

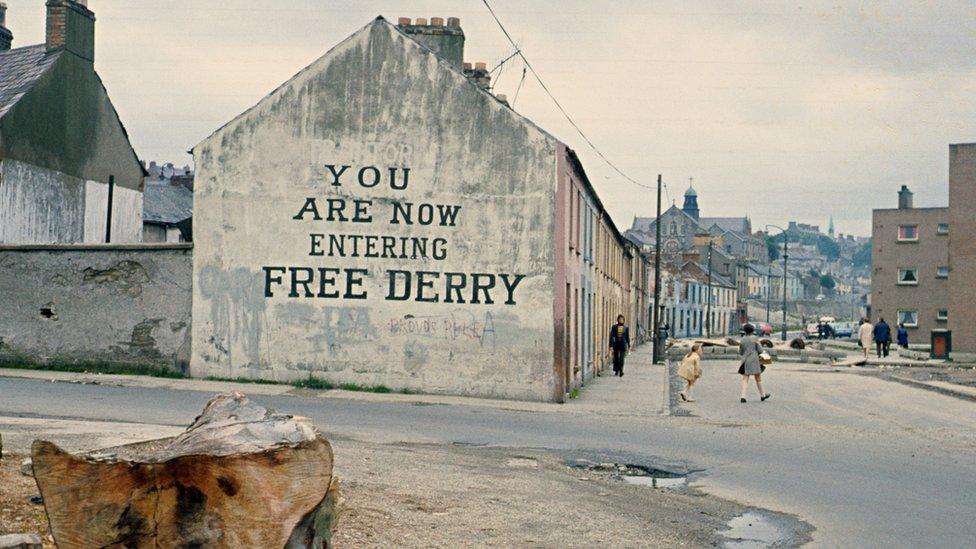

A separate march organised by the Bloody Sunday March Committee, from Creggan to Free Derry Corner, also took place on Sunday.

A chime for every life lost

At the scene: Mike McBride, BBC News NI

People gather in the Millennium Forum for a special commemoration event half a century on since one of Derry's darkest days.

A minute's silence is observed in the amphitheatre, as the names of those killed on Bloody Sunday are read out to a hushed audience.

The poignant moment takes place as the bells of St Eugene's Cathedral ring out across the city. A chime for every life lost.

Actor Adrian Dunbar, who is hosting the event, struggling to find words, says the emotions in the city today are truly palpable 50 years on from the atrocity.

The walk of remembrance retraced the steps of the original march in 1972

A day of commemorative events had started with the families walking the same route their relatives had tried to walk five decades ago. Hundreds joined them along the way.

A January day that started in peaceful protest, but ended in tragedy.

John Kelly, the brother of Michael Kelly, handed out a white rose to a child representing each of the Bloody Sunday families.

Each rose representing a loved one tragically taken that day.

On Wednesday, Prime Minister Boris Johnson paid tribute to victims' families during Prime Minister's Questions.

Mr Johnson described Bloody Sunday as "one of the darkest days in our history" and said in the run up to the anniversary "we must learn from the past, reconcile and build a shared and prosperous future".

Ahead of the 50th anniversary, ex-prime minister David Cameron said his 2010 apology for Bloody Sunday made it clear there was no doubt what happened was wrong.

When the Saville Inquiry was released, Mr Cameron apologised for the "unjustified and unjustifiable" deaths.

What happened on Bloody Sunday?

Thousands gathered in Derry on that January day for a rally organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.

They were protesting against a new law giving the authorities powers to imprison people without trial - internment.

The Stormont government had banned such protests, and deployed the Army.

Many demonstrators marched towards Free Derry Corner

The intended destination of the demonstrators was the city centre, but Army barricades blocked marchers, so many demonstrators headed towards Free Derry Corner in the Bogside.

After prolonged skirmishes between groups of youths and the Army, soldiers from the Parachute Regiment moved in to make arrests.

Just before 16:00 GMT, stones were thrown and soldiers responded with rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannon.

At 16:07 GMT, paratroopers moved to arrest as many marchers as possible. At 16:10 GMT, soldiers began to open fire.

Jean Hegarty, whose 17-year-old brother Kevin McElhinney was shot and killed on Bloody Sunday, said it was hard to believe 50 years had passed.

Kevin, who worked at a local supermarket, was killed as he attempted to flee the firing on Rossville Street.

Jean Hegarty looks out at the spot where her brother Kevin McElhinney, aged 17, was killed on Bloody Sunday

"It never gets easier to talk about, even after all this time, for some of us [the Bloody Sunday families] it still sadly feels like it happened just yesterday," Ms Hegarty told BBC News NI.

She says Sunday is an extremely emotional day for the families.

The years after Bloody Sunday

Guildhall Square was packed for David Cameron's apology on behalf of the state in 2010

Two public inquiries have been carried out into the events of Bloody Sunday.

The Widgery Tribunal, which was announced shortly after Bloody Sunday, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame.

The Saville Inquiry, published in 2010, found none of the casualties was posing a threat or doing anything that would justify the shooting.

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) began a murder investigation in 2010.

Detectives submitted their files to the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) towards the end of 2016.

Prosecutors said in 2019 they would prosecute a soldier, known only as Soldier F, for the murders of James Wray and William McKinney on Bloody Sunday.

On 2 July 2021, it was announced Soldier F would not face trial following a decision by the PPS.

The decision not to proceed with the case is now the subject of live judicial review proceedings following a legal challenge brought by a brother of one of the Bloody Sunday victims.

- Published28 January 2022

- Published24 January 2022

- Published26 January 2022