Brexit: The NI Protocol and its economic impact

- Published

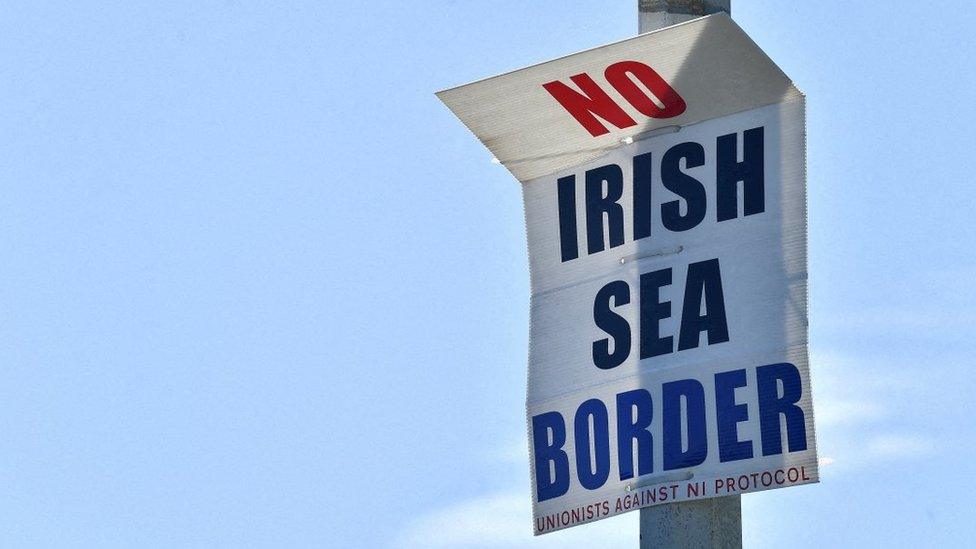

Under the protocol, checks are required on goods coming into Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK

The Northern Ireland Protocol keeps Northern Ireland (NI) inside the European Union's (EU) single market for goods.

That means products coming from Great Britain (GB), which is NI's main source of imports, face additional costs in terms of new processes and paperwork.

This extra cost will eventually have to show up as increased consumer prices or lower business profits.

The economic flipside is that Northern Ireland businesses now have an advantage over GB exporters because they still have full access to both the EU single market and the rest of the UK.

This dual market access potentially makes Northern Ireland a more attractive location for manufacturing investment.

So the questions economists are trying to answer are:

How big are the costs of the GB-to-NI trade barriers?

To what extent is that offset by trade and investment opportunities?

Esmond Birnie Analysis

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is mainly relying on estimates produced by Northern Ireland economist Esmond Birnie, external.

His analysis is based on a limited dataset - the experience of four companies, including an extrapolation of figures in Marks and Spencer's financial accounts.

He uses that to estimate that NI businesses have faced an increase of around 6% in the cost of bringing goods into Northern Ireland from GB.

The total flow of goods and materials coming into Northern Ireland from GB is about £10bn a year so the rise in costs is equivalent to a bill of about £600m annually.

In order to get to an annual cost of £850m he adds the estimated £250m a year which the UK government is spending to assist businesses with the impact of the Protocol.

He treats this as an opportunity cost - in other words this money is not being spent on something more productive like education.

However, it is debatable whether that entire opportunity cost should be applied to Northern Ireland.

Given that the money is being spent by central government, not Stormont, it is arguable that a population share of 3% should be applied to Northern Ireland which is £7.5m.

Dr Birnie's analysis does not attempt to calculate any offsetting impact from more trade with the EU and he has been very sceptical of official data which suggests there has been a big increase in cross-border trade with the Republic of Ireland.

We also don't have good data on what has happened to Northern Ireland sales to Great Britain.

SDLP MLA Matthew O'Toole has critiqued the analysis on the basis that it is implicitly modelled against a "no-Brexit scenario".

He says: "That is self evidently flawed; the alternative to the protocol is not trade as it was before Brexit, because it can't be."

Sinn Féin's economy spokesperson Caoimhe Archibald has also said the question of what the protocol is being compared to is important.

'Any serious assessment of the protocol would also compare it against the alternative [in technical terms the counterfactual]. Britain's Brexit also carries costs, not least barriers to trade with the EU, but Mr Birnie ignores these,' she said.

Fraser of Allander forecast

The second, more substantial, piece of work is a forecast from the Fraser of Allander Institute, an economics research institute based at the University of Strathclyde.

It uses an economic model to estimate the medium term impact of the protocol on the Northern Ireland economy, so it is not making claims about the current daily or annual costs of the Protocol.

It is explicitly comparing the impact of the protocol to a scenario in which the UK had stayed in the EU.

The model does not consider the impacts of migration, foreign direct investment or economic spill-over effects from Great Britain.

It does include the impact of new barriers to services trade between Northern Ireland and the EU, something not covered by the Protocol.

It finds that in the medium term the protocol would leave Northern Ireland's economy 2.6% smaller compared to a scenario in which the UK had stayed in the EU.

In cash terms that would be about £900m - £1bn of foregone output.

It finds that these impacts can potentially be halved by firms in Northern Ireland sourcing a lot more goods from the EU rather than GB.

Alternatively, in a scenario in which checks and controls from GB to Northern Ireland can be reduced, the economic hit would fall to 1.5% - this is what the current negotiations between the EU and UK are trying to achieve.

What about a comparison with the UK as a whole?

The UK budget watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), estimates that in the long run the UK's economic output will be 4% lower compared to a scenario where it stayed in the EU.

Its forecasts assume that total UK imports and exports will eventually both be 15% lower than if the UK stayed in the EU.

This reduction in trade intensity drives the 4% reduction in long-run potential productivity it assumes will eventually result from the departure from the EU.

- Published2 February 2024

- Published2 February 2022

- Published3 February 2022