Anorexia: Daughter's death prompts call for more training

- Published

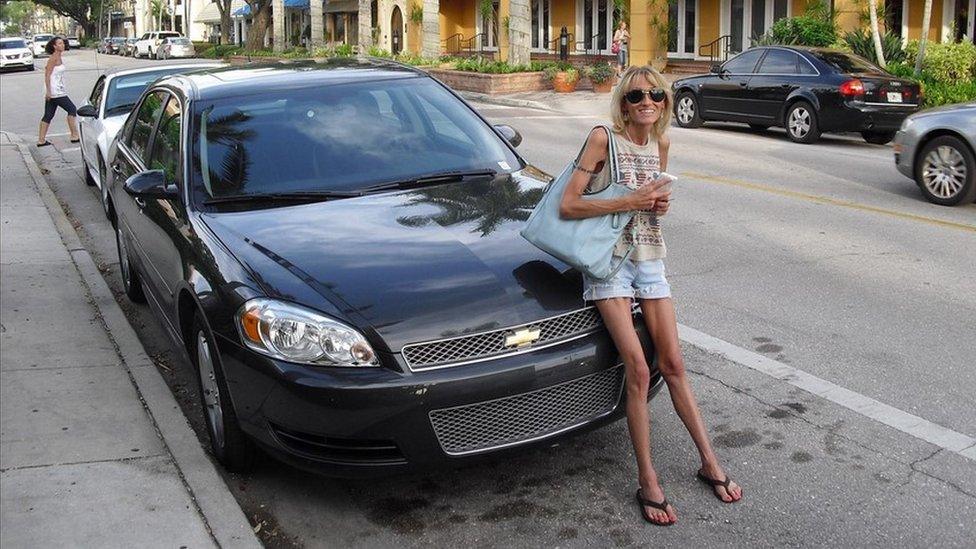

Marilyn Kelly's daughter, Cathie (right), died from anorexia aged 34

The mother of a woman who died after battling anorexia for 13 years has said there is "too much of a one-size-fits-all approach" to treating patients, like her daughter.

Cathie Kelly weighed just a few stone when she died in 2019, aged 34.

Her mother, Marilyn, said things may have been different had medical staff received more training.

The Department of Health said the existing mental health workforce in Northern Ireland is being reviewed.

Eating disorder charity Beat said that while healthcare staff across Northern Ireland are "working tirelessly" to provide the best care to eating disorder patients, they often do not have enough training in this area, "through no fault of their own".

Cathie Kelly developed an eating disorder in her early 20s

Cathie Kelly, from Newtownards, County Down, loved horse-riding and sport.

Her eating disorder began in her early 20s and after noticing fluid retention in her legs resulting from low food intake, Cathie visited her doctor and was diagnosed with anorexia.

Her health quickly deteriorated and after being referred to an eating disorder service, she was admitted to a mental health hospital ward under 24/7 observation.

Wanting to return home, Cathie's mum became her carer. However, Mrs Kelly said ambulance crews were called to their house at least once a month, as her daughter developed a range of health issues stemming from anorexia.

In summer 2018, Cathie was admitted to hospital again and needed fed through a gastro-nasal tube but her nose had become too fine for the tube to be fed through, meaning she had to be drip fed.

Cathie Kelly was a keen equestrian at the peak of her health

Cathie's illness progressed through the years and she opted to go on to palliative care.

"Most of the doctors that we encountered did their best but there is a distinct lack of knowledge and too much of a one-size-fits-all approach to treatment," said her mother.

Medical staff were well intentioned but "there needs to be a closer pathway between medical science and psychiatric science and greater awareness and training", she added.

'Became my enemy'

Ali North, 52, from Belfast, began limiting her food intake in her teenage years after childhood trauma.

"I had nobody and I turned to my eating disorder as my friend, but it became my enemy," she said.

She knew she needed help but, at the time, felt that her GP was not supportive enough.

Her periods stopped, her weight continued to drop and she "had blue skin".

Eventually, she was referred to an eating disorder specialist which says saved her life.

Ali North, 52, has lived with an eating disorder for 30 years

Having lived with an eating disorder for 30 years, Ali is now in recovery but she called for more medical training on "a major illness that takes so many lives".

The Department of Health said that under its Mental Health Strategy 2021-2031, new models of working will be considered to inform decisions around where the focus on training, recruitment and retention needs to be.

It said this will help create a workforce for the future that will "meet the needs of the population".

"This will include consideration of the number of training places, in addition to the commissioning of pre-registration training and, also, post-registration training requirements," the department added.

The Mental Health Champion for Northern Ireland, Prof Siobhan O'Neill, said that over £3.6m is needed over the next three years to improve eating disorder services and treatments in Northern Ireland.

Eating Disorders Association NI said January 2022 was their busiest month on record since they opened in 1992.

"We believe that a lack of appropriate eating disorder training needlessly increases the difficulty of GP's work and that this can lead to some patients having a negative experience," a spokesperson said.

Longer consultations needed

Dr Gary Howsam, vice-chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), said that during a trainees' three-year specialty training "they must demonstrate competence of the entire GP curriculum, which has a significant focus on mental health, including eating disorders".

He said eating disorders are complex and the standard 10-minute appointment is "inadequate" for GPs to have the necessary conversations with patients.

Dr Alan Stout, from the British Medical Association, said that as well as additional training at medical school, "we also need to be able to quickly refer the patient to other appropriate services that are easily accessible, preferably in their local community".

If you've been affected by eating disorders, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.

Related topics

- Published27 February 2017

- Published7 August 2021

- Published15 November 2020